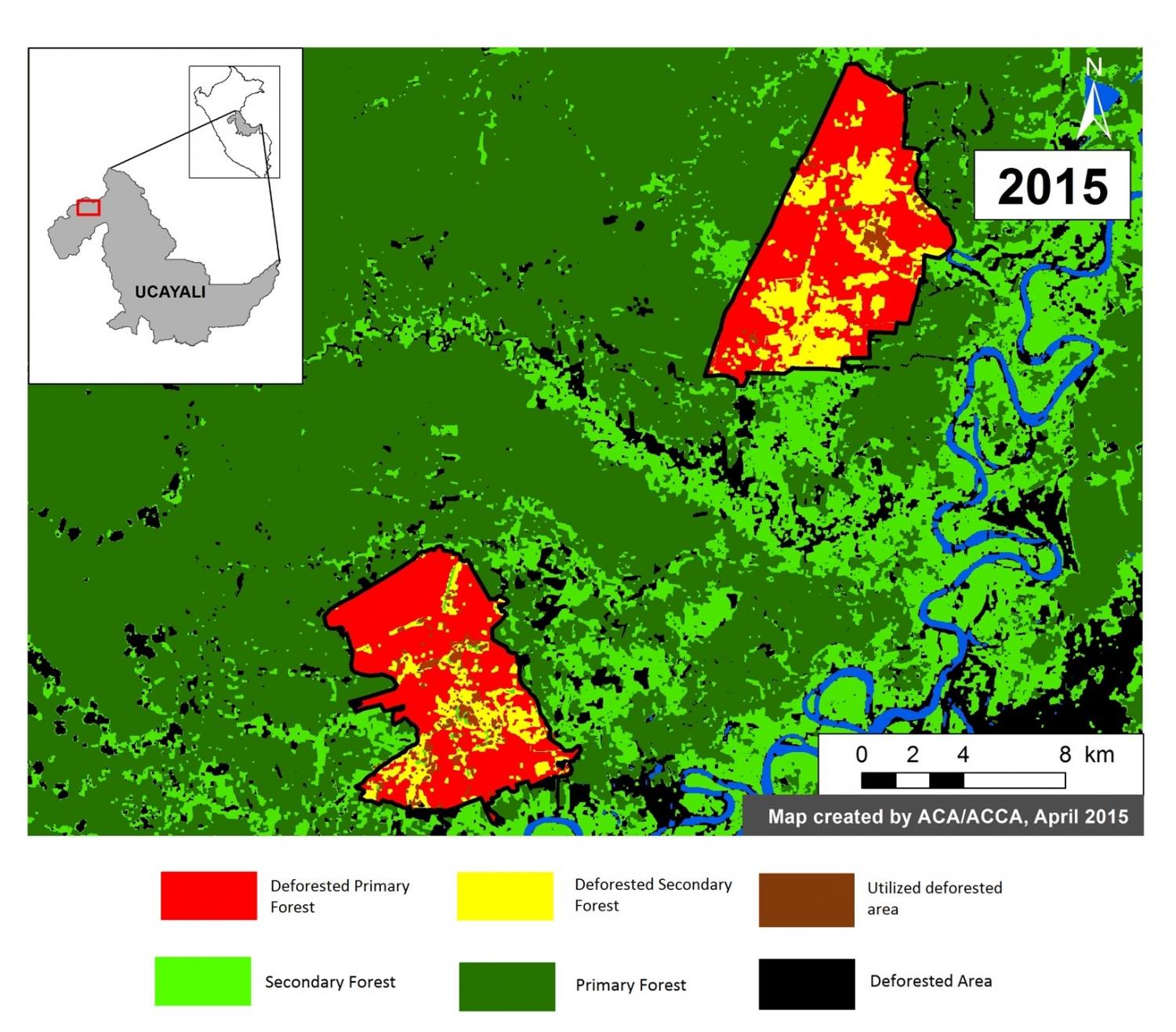

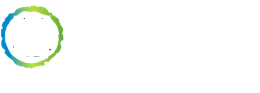

Image of the Week #4 shows the expansion of two large-scale oil palm projects near the town of Nueva Requena in the central Peruvian Amazon (Department of Ucayali). These projects began in late 2011 and, as of April 2015, now cover nearly 12,200 hectares (ha). Our analysis reveals that, of this total area, 9,400 ha came at the expense of primary forest and 2,350 ha from secondary forest.

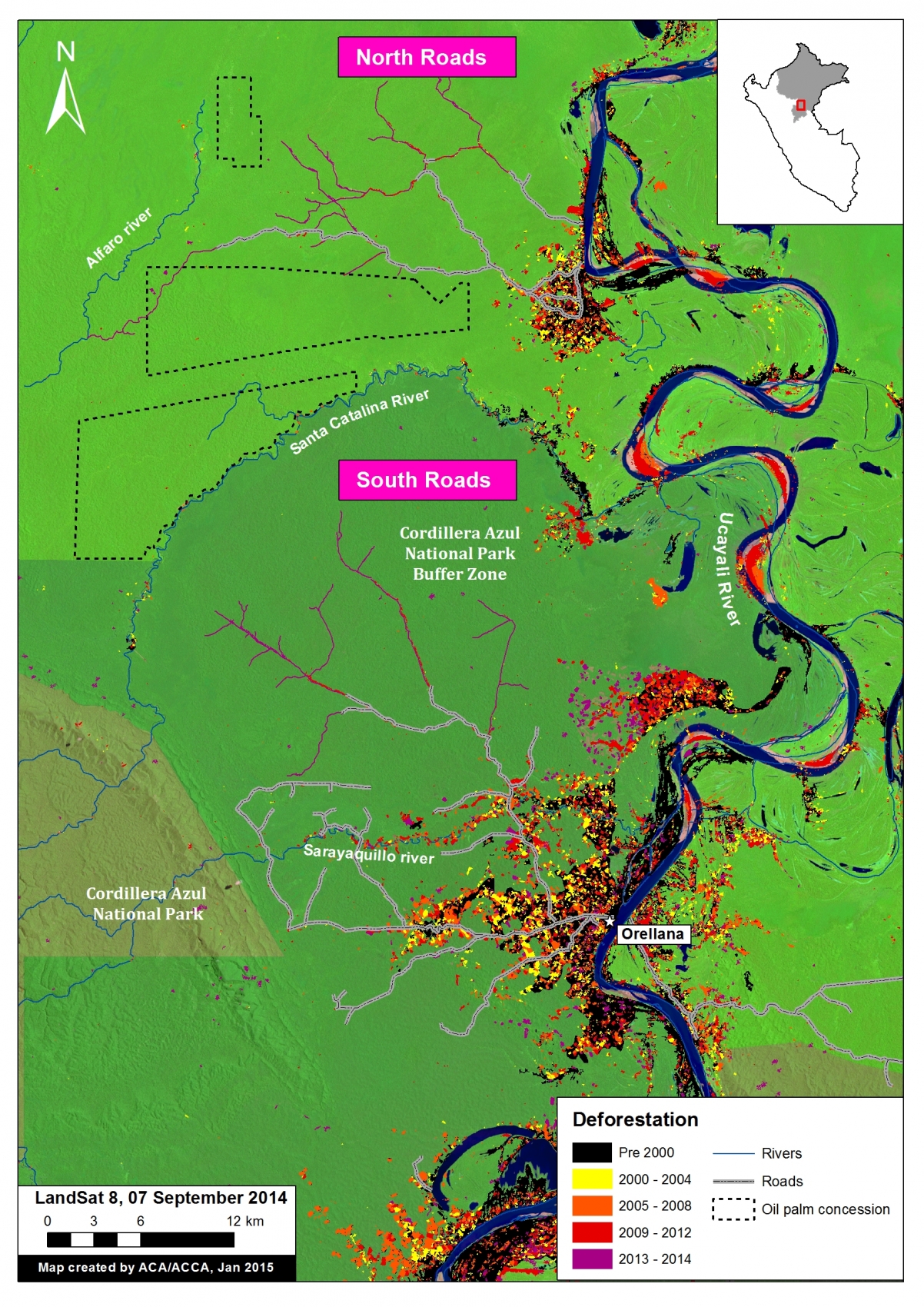

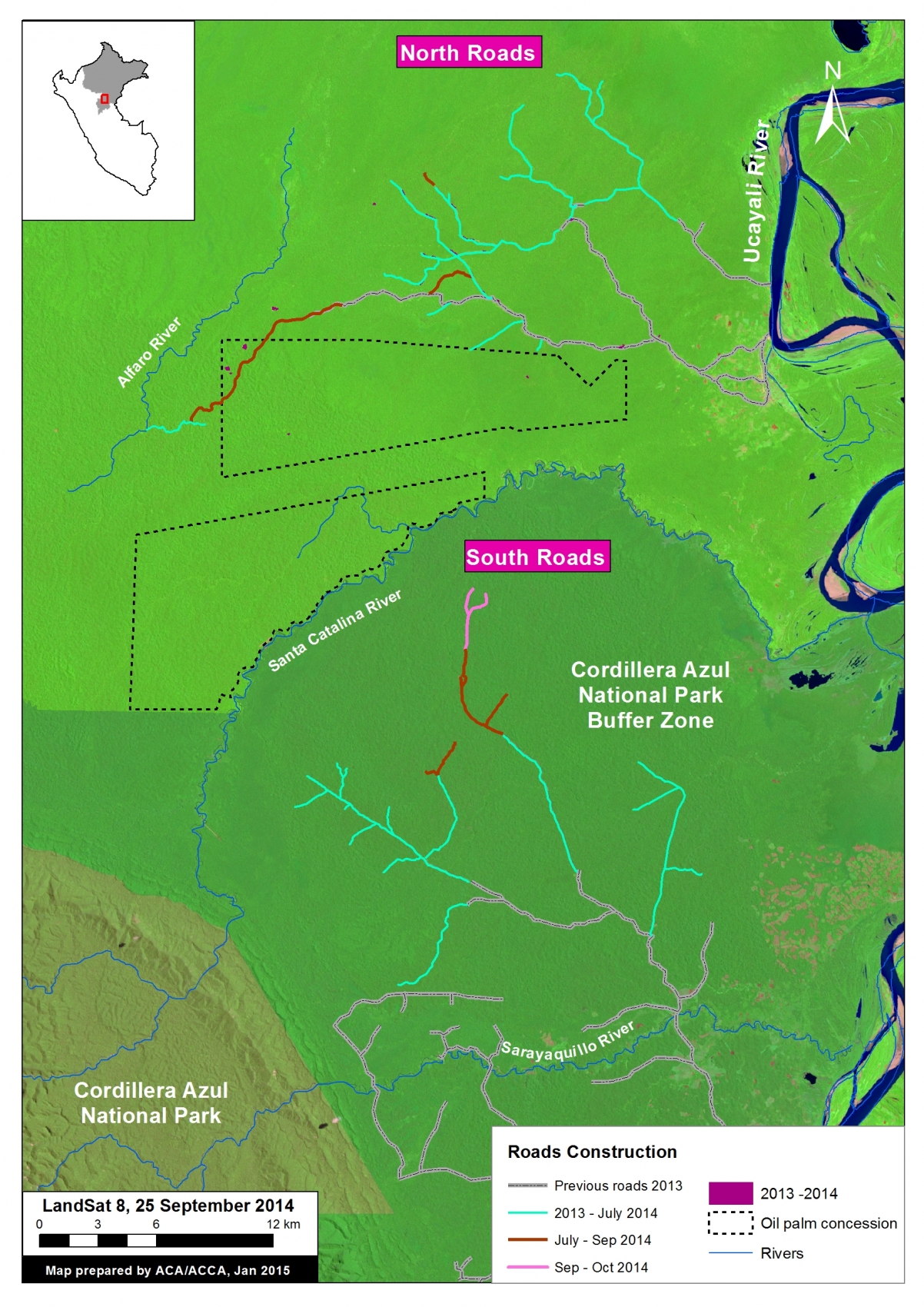

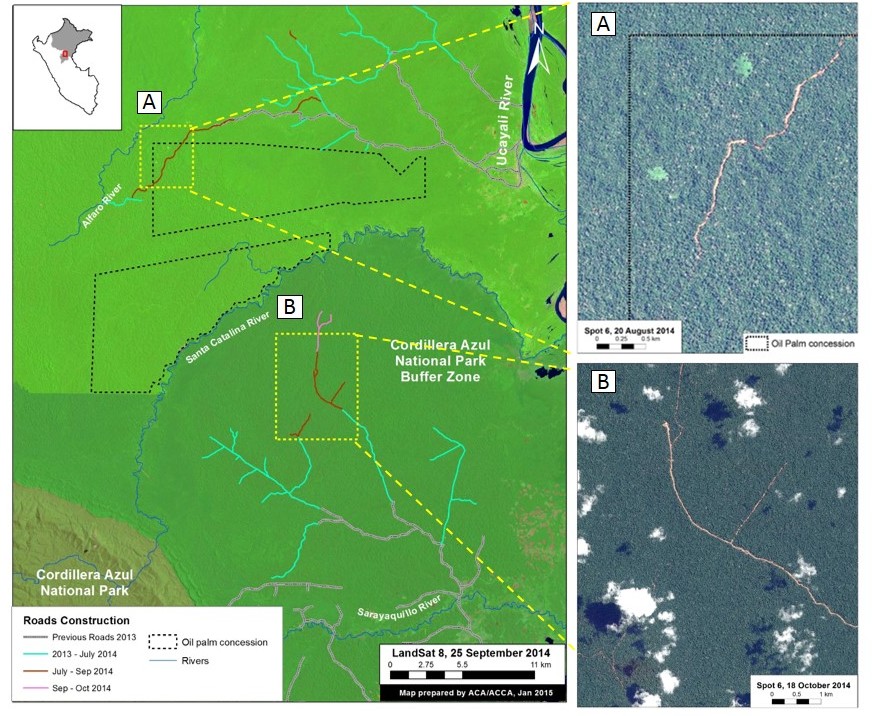

Map Description

Background map is a Landsat 8 satellite image (30 meter resolution) from August 2014. Dark green indicates forest cover. Light green indicates younger or secondary vegetation. Blue indicates water bodies. Data is from USGS.

The dashed black lines indicate the outline of the two large-scale oil palm projects, one of which is known to be “Plantaciones de Ucayali”, as of April 2015.

The colors indicate how the deforestation and plantation installation unfolded over time for the two projects according to our analysis of Landsat imagery.

Between October 2011 and August 2012, large scale-clearing and installation (indicated in yellow) started in the northern project.

Between September 2012 and August 2013, large-scale clearing and installation (indicated in orange) continued in the northern project and began in the southern project.

Between September and November 2013, clearing and installation (indicated in red) continued in the southern portion of both projects.

Most recently, between December 2013 and April 2015, clearing and installation (indicated in purple) continued in the southern portion of the northern project.

As of April 2015, the two projects cover an area of 12,188 ha.

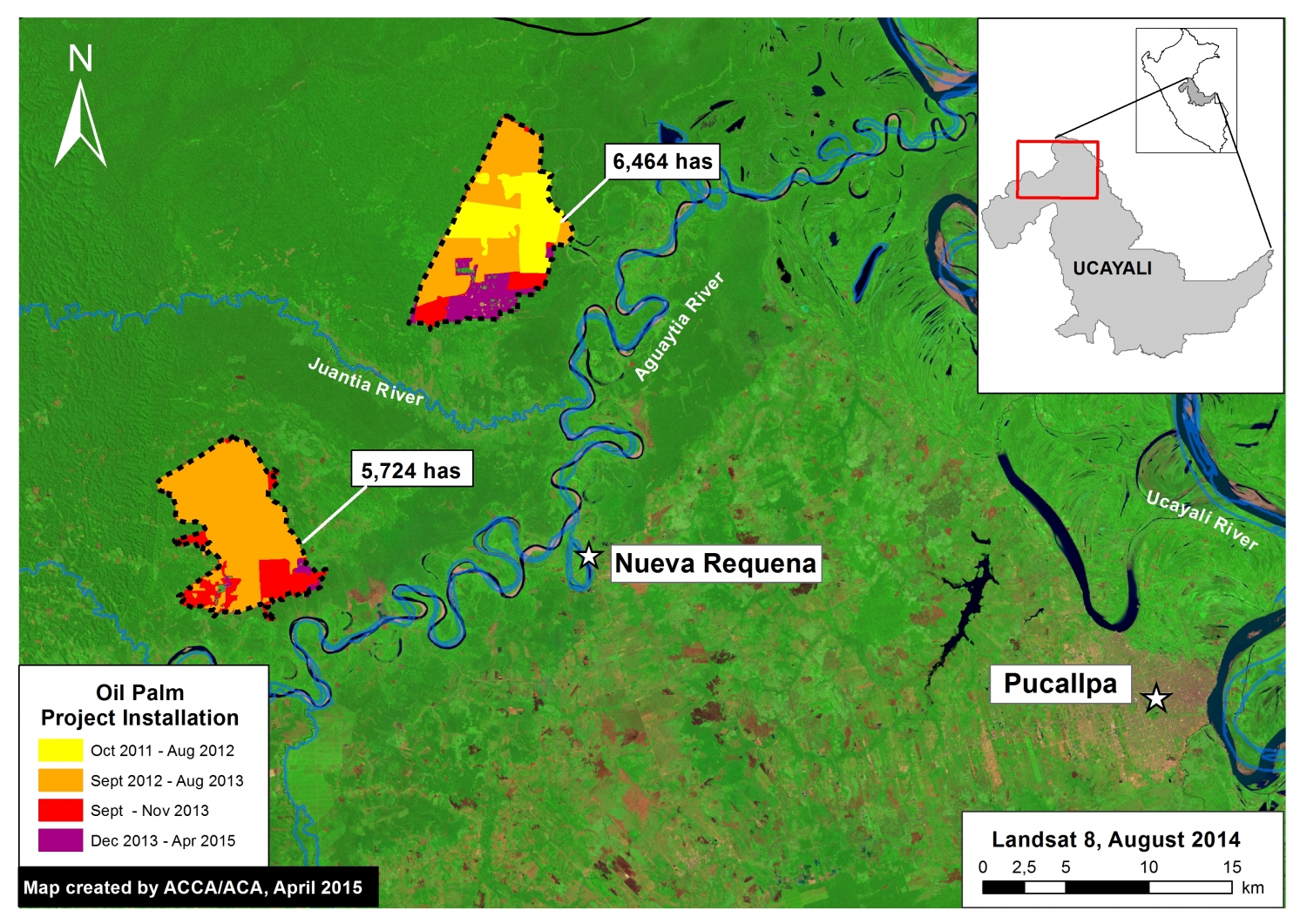

Landsat Time-series 2010 – 2015

Image 4b is a series of Landsat images showing the change over time for both oil palm projects. In these images, dark green indicates forest cover, light green indicates secondary vegetation and oil palm plantations, pink indicates exposed ground (and is therefore a key indicator of recent deforestation), and the scattered white and black spots indicate clouds and their shade.

The first image, Landsat 5 from August 2010, shows the eventual project area (indicated by dashed black lines) immediately prior to the start of the project in 2011.

The second image, Landsat 7 from July 2012, shows the start of large-scale clearing in the northern portion of the project area.

The third image, Landsat 8 from September 2013, shows the clearing quickly expanded in both projects. It also shows the start of the oil palm plantation planting in the northern project (indicated by bright green).

The fourth image, Landsat 8 from April 2015, is the latest cloud-free image for the project area. It shows the continued expansion of the northern project and the extensive oil palm plantation plantings in both projects.

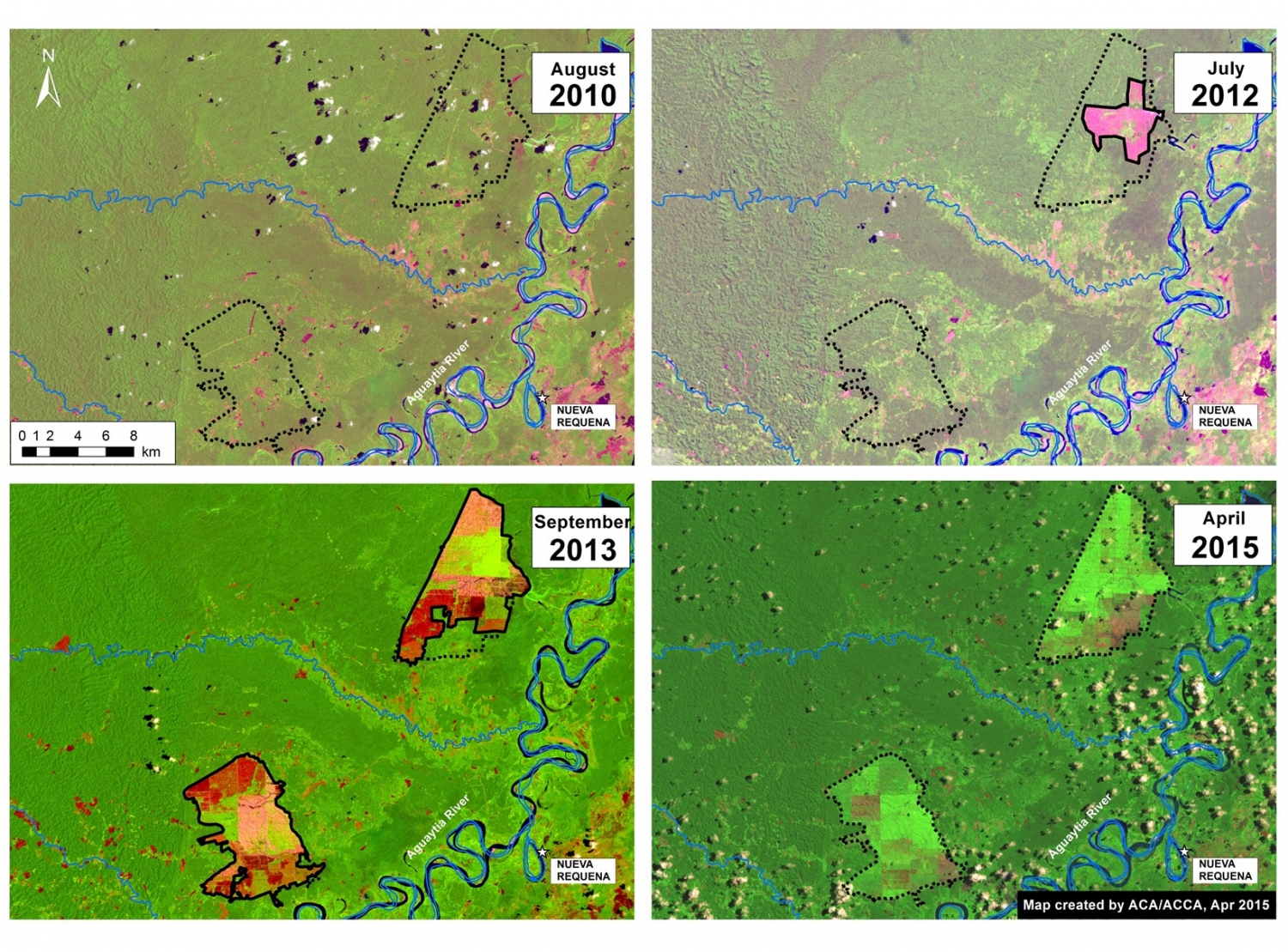

Landsat Time-series 1990 – 2015

We conducted another Landsat time-series analysis, but going back further in time (to 1990) in order to better understand the state of the forests cleared for the oil palm project. For each image, we determined whether an area was primary forest, secondary forest, deforested, or oil palm. Image 4c illustrates the results of this analysis.

It is important to note that in 2010, just prior to the large scale clearing, the two project areas were mostly a mix of primary and secondary forest.

Deforestation of Primary Forest

Finally, we used the results from the Landsat time-series analysis to conduct a classification of land use prior to oil palm activities.

We determined that, of the 12,188 ha of the two oil palm projects, 9,404 ha (77%) was primary forest immediately prior to project installation. That is the equivalent to nearly 7,000 soccer fields. An additional 2,350 ha (19 %) was secondary forest. Only 434 ha (4 %) was already deforested at the start of the project.

We defined primary forest as an area that from the earliest available Landsat, in this case 1990, was characterized by dense closed canopy forest cover.

This work builds off of the following publication: Environmental Investigation Agency. Deforestation by Definition. 2015. Washington, DC. http://eia-global.org/news-media/deforestation-by-definition

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S (2015) Large-Scale Oil Palm Causes Deforestation of Primary Forest in the Peruvian Amazon (Part 1: Nueva Requena). MAAP: Image #4. Link: https://www.maapprogram.org/2015/04/image-4-oil-palm-projects-cause-deforestation-of-primary-forest-in-the-peruvian-amazon-part-1-nueva-requena/