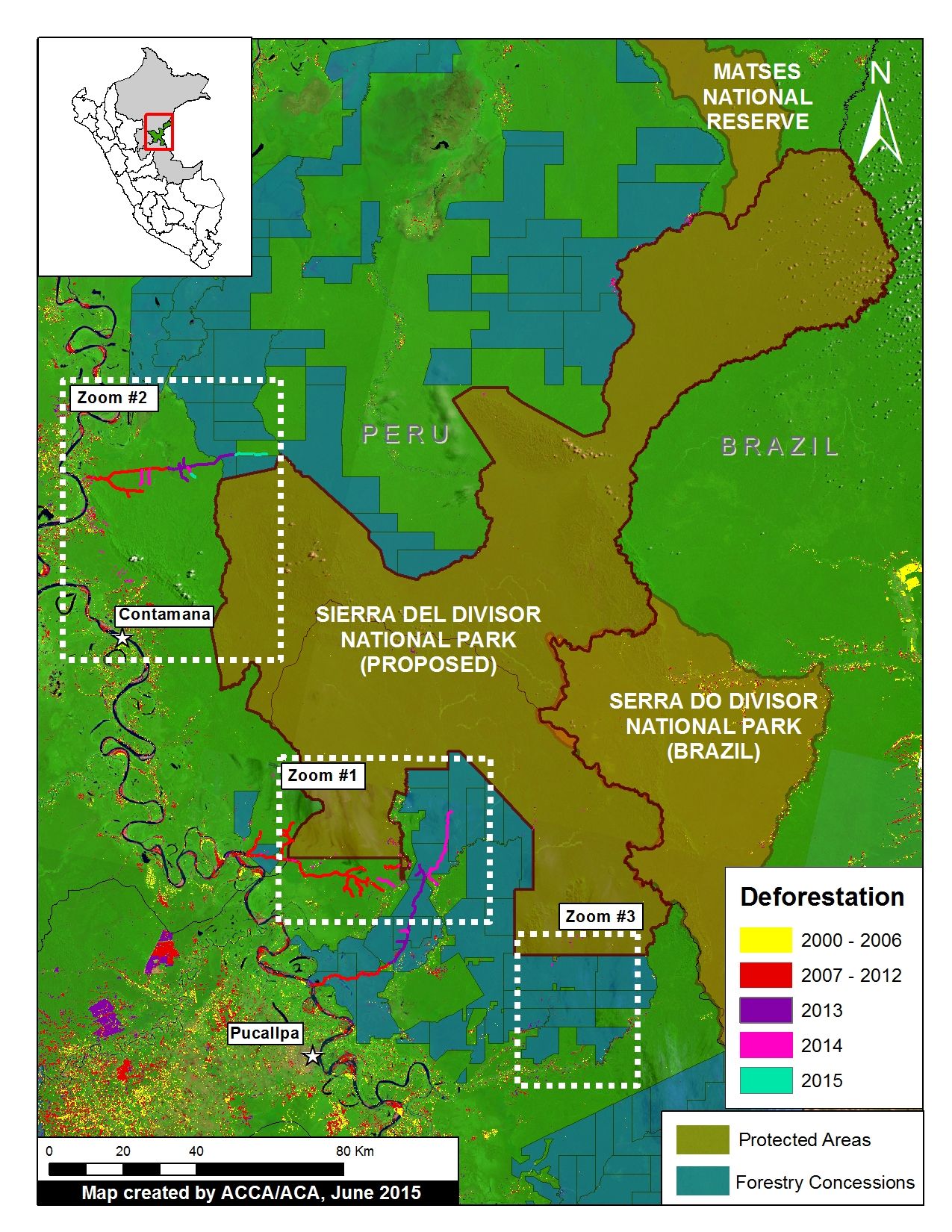

Recall that in Image #2 we documented the rapid clearing of 2,126 hectares of primary forest between May 2013 and August 2014 for a new cacao project outside of the town of Tamshiyacu in the northern Peruvian Amazon (Department of Loreto).

However, the company that carried out the forest clearing (United Cacao, through its wholly-owned subsidiary in Peru, Cacao del Peru Norte) has responded “that this area had been used for farming since the late 1990s, and thus it was not primary forest…There was no high-conservation-value forest on that land (Cannon JC, 2015, mongabay.com).” In addition, the company’s website states that “The site was heavily logged of all tropical hardwoods in the 1980s.”

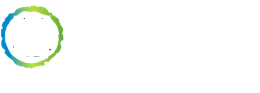

Here, in Image #9, we 1) publish new high-resolution (33 cm) satellite imagery that shows how the cacao project is expanding into dense, closed-canopy forest and 2) detail exactly how we determined that the vast majority of the clearing indeed came from primary forest. These findings are critically important because the company has major expansion plans.

Key Results:

We obtained very high-resolution (33 cm) satellite imagery taken over the United Cacao plantation in June 2015 (see Image 9a). In this imagery, one can clearly see that the cacao project is embedded and expanding into dense, closed-canopy forest.

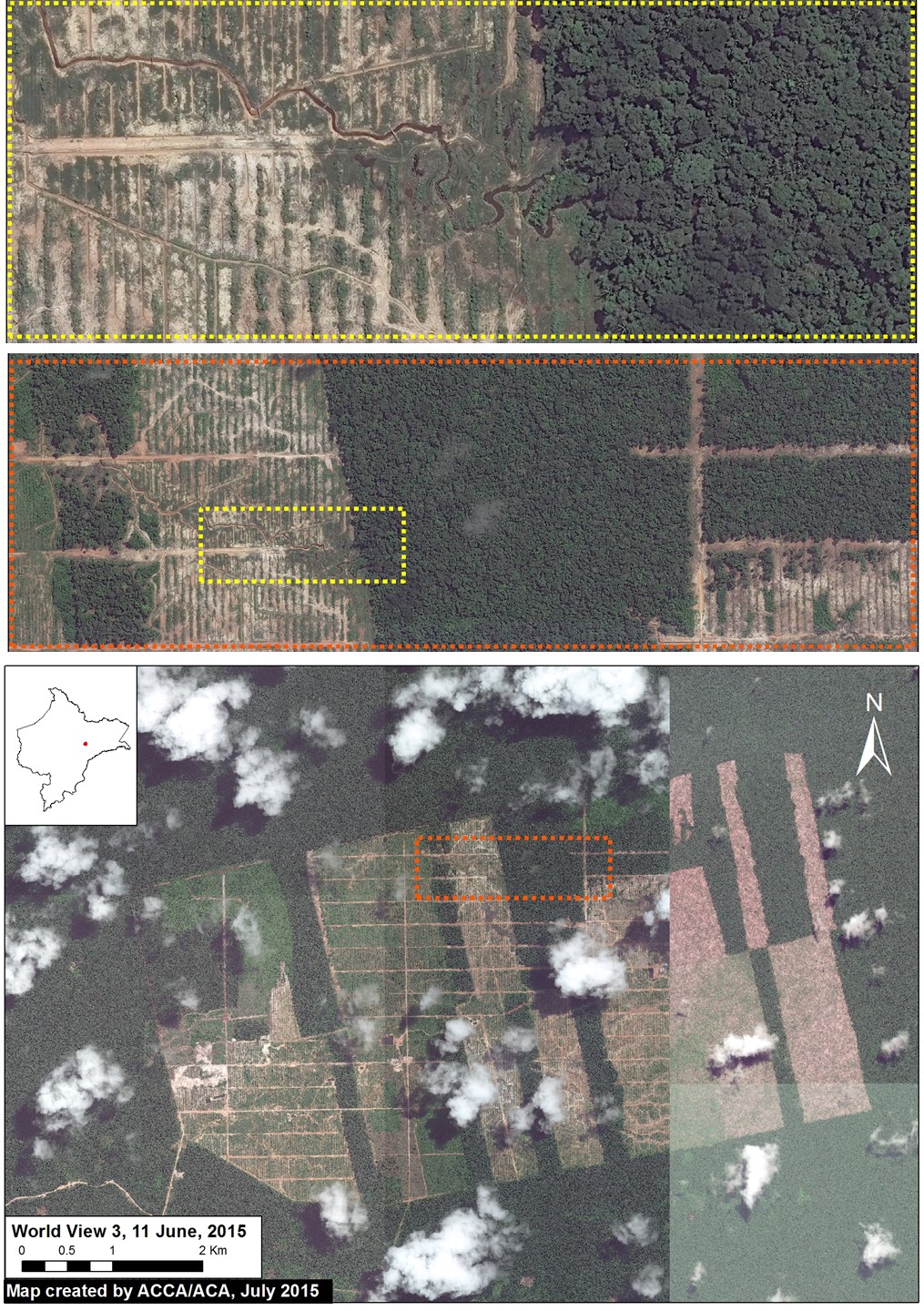

We analyzed a series of satellite (Landsat) images dating back to 1985 to determine that, prior to the arrival of United Cacao in 2013, the project area 1) had NOT been used for major farming activities, 2) was NOT heavily logged of all tropical hardwoods, and 3) was dominated (98%) by primary forest (see Image 9b). In fact, by analyzing spectral signatures in the Landsat images, we confirm that the area cleared by United Cacao in 2013 was dominated by primary forest (see Image 9c).

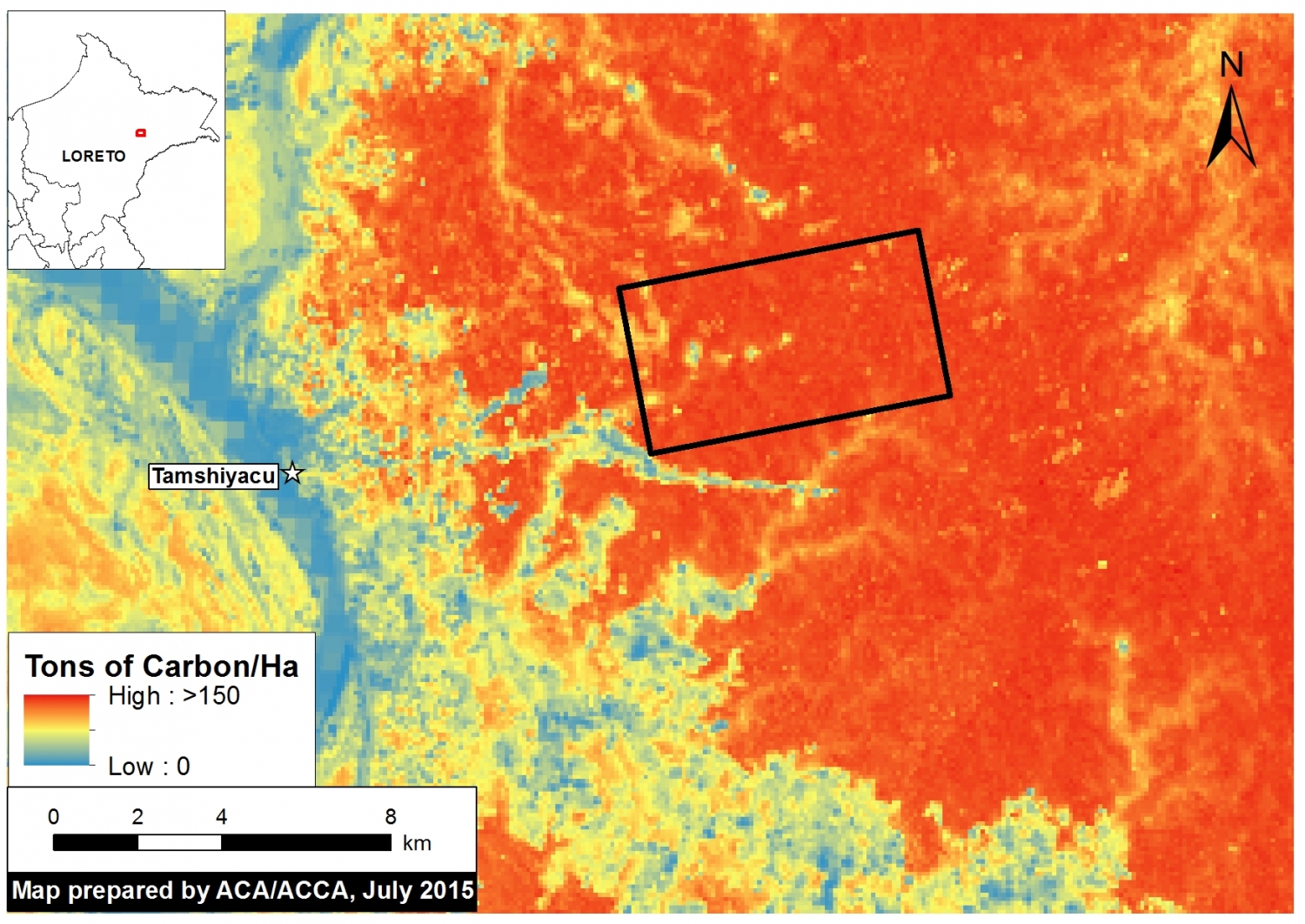

We show data from the Carnegie Airborne Observatory showing that the majority of the United Cacao project area had the highest possible value of carbon (over 150 tons per hectare) immediately prior to the forest clearing in 2013.

Finally, we present information indicating that the current documented forest clearing of 2,126 hectares may soon double or triple.

Landsat Time-series

Image 9b displays a series of Landsat images dating back to 1985 showing that, prior to the arrival of United Cacao, the area was dominated (nearly 98%) by primary forest and NOT used for major agriculture activities or heavily logged of all tropical hardwoods.

In these Landsat images, dark green indicates forest cover, light green indicates secondary vegetation, pink indicates exposed ground (and is therefore a key indicator of recent forest clearing), and the scattered white and black spots indicate clouds and their shade.

In 1985, the future cacao project area (indicated by black box) was completely covered by forest with no signs of clearing, major logging, or farming. By 1995, there were a few scattered areas of cleared forest in the center of the future project area. By 2005, there was a slight expansion of these cleared areas in the center of the future project area. By 2012, immediately before the start of forest clearing, the future project area appeared much the same: a few scattered areas of cleared forest in the center, but the vast majority of the area was primary forest.

We defined primary forest as an area that from the earliest available image (in this case, from 1985) was characterized by dense closed-canopy coverage and experienced no major clearing events.

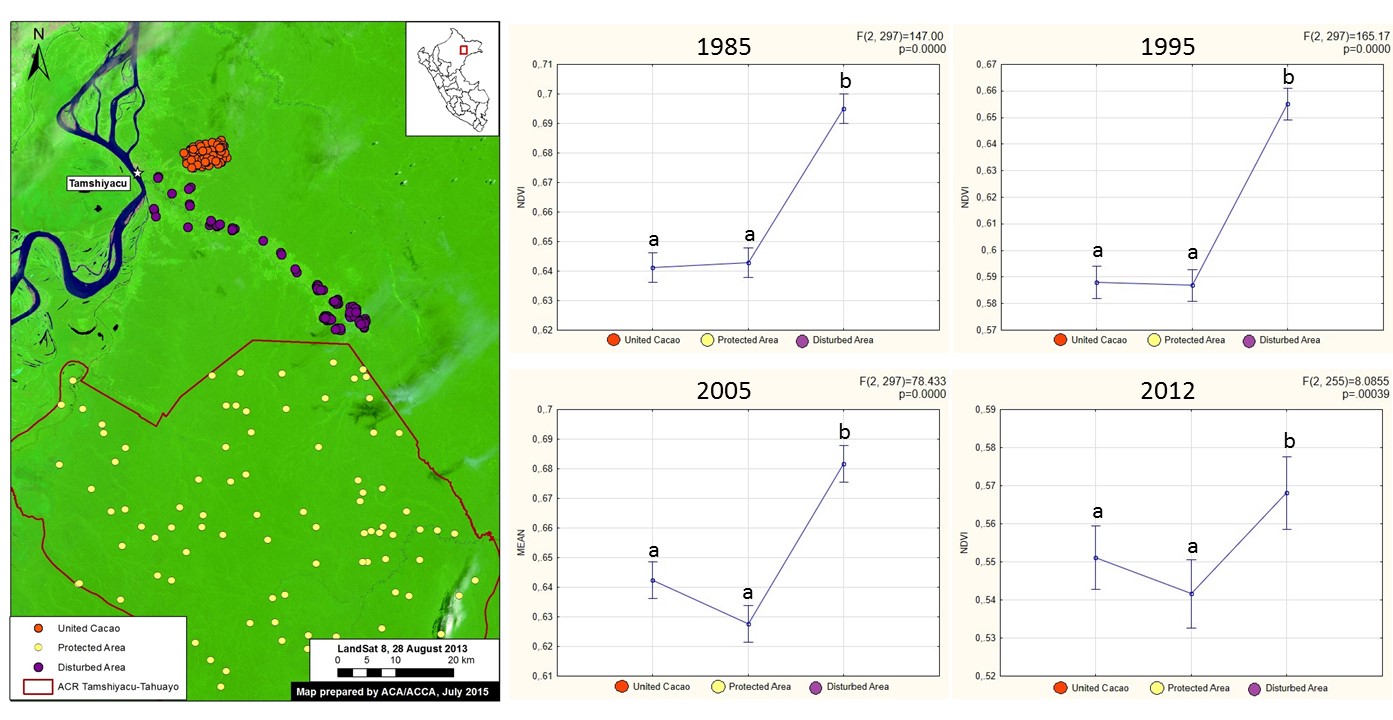

NDVI Analysis

To further investigate the issue of primary forest, we used the Landsat imagery to conduct an NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) analysis. NDVI is a common index of photosynthetic activity, or “greenness,” based on the fact that different surfaces (primary forest, secondary forest, water, bare ground, etc…) reflect light (visible and near-infrared) differently.

As seen in Image 9c, we obtained NDVI measurements across four different years (1985, 1995, 2005, and 2012) for 100 random points from each of three different areas: 1) area cleared by United Cacao in 2013 (orange dots), 2) nearby protected area that is proxy for primary forest (yellow dots), and 3) disturbed area along a major river that is proxy for secondary forest (purple dots).

For all four years, we found that the NDVI values for the area cleared by United Cacao in 2013 were similar to those of the nearby protected area (in fact, these values were nearly identical in 1985 and 1995), but significantly different than the disturbed area along the major river. In other words, the forest cleared by United Cacao was nearly identical to our proxy for primary forest and significantly different than our proxy for secondary forest. Thus, we conclude that United Cacao cleared over 2,000 hectares of primary forest in 2013.

Carbon Data Tells the Same Story

The Carnegie Airborne Observatory, led by Dr. Greg Asner, and the Peruvian Ministry of Environment, recently produced a high-resolution carbon geography of Peru. Interestingly, they mapped the carbon content of the United Cacao plantation area immediately prior to the forest clearing.

As seen in Image 9d, the vast majority of the United Cacao project area had the highest possible value of carbon (over 150 tons per hectare) immediately prior to the forest clearing in 2013. The only exceptions were the scattered previously cleared areas identified in Image 9b.

According to Asner, “The carbon levels were extremely high, indicating that they were large, intact forests that we normally picture when we think of primary Amazon forest.”

More Forest Clearing Coming…

According to its website, United Cacao owns around 3,250 hectares near Tamshiyacu, and this total may soon increase to 4,000 hectares. In addition, the company has started an initiative with local farmers that may include an additional 3,250 hectares.

Thus, the current documented forest clearing of 2,126 hectares may soon double or triple.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that we detected a sawmill within the project area. This discovery raises the question, Has the company obtained the necessary permits for this activity?

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S (2015) Demonstrating that Forest Clearing for Cacao in Tamshiyacu (Loreto, Peru) came from Primary Forest. MAAP: Image #8. Link: https://www.maapprogram.org/2015/06/image-9-cacao-tamshiyacu/