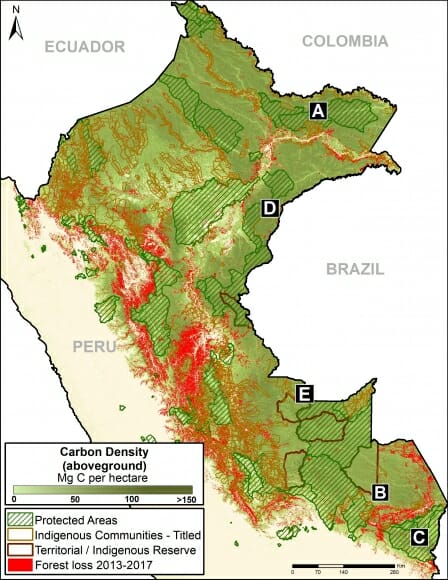

The efforts and international commitments of the Peruvian Government to reduce deforestation may be compromised by new projects do not have adequate environmental assessment.

In this series, we address the most urgent of these projects, those that threaten large areas of primary Amazonian forest.

We believe that these projects require urgent attention from both government and civil society to ensure an adequate response and avoid irreversible damage. For example, in the case below, it is not known whether there is an environmental impact study.

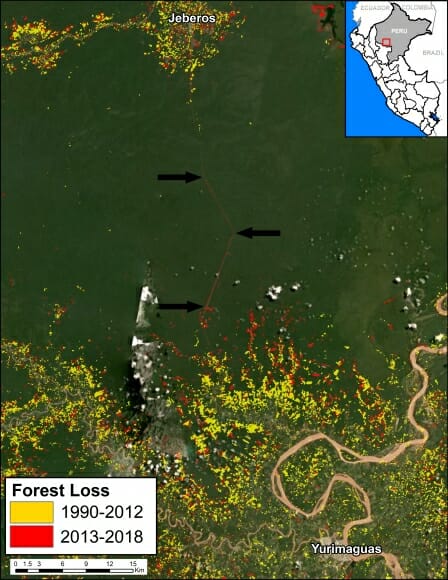

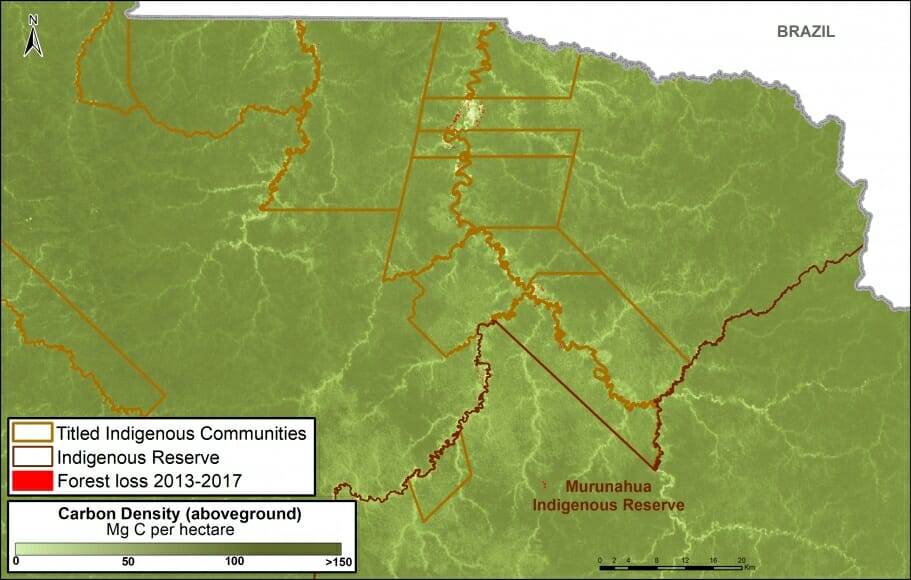

The first report of this series focuses on a new road (Jeberos – Yurimaguas) that threatens a large expanse of primary forest in the northern Peruvian Amazon (see Image A).

Yurimaguas-Jeberos Road

Early warning forest loss alerts (GLAD alerts from the University of Maryland and Global Forest Watch) have detected the construction of a new road between the city of Yurimaguas and the town of Jeberos, in southern Loreto region (see Image B).

We estimate that the new road is 65 km (40 miles). In the image, the arrows indicate part of the route crossing primary forest (indicated in dark green).

Although the road improves the connectivity of an isolated town, the problem is that much of it crosses primary Amazon forest and may trigger massive deforestation. It is well documented that roads are one of the main drivers of deforestation in the Amazon (see MAAP #76).

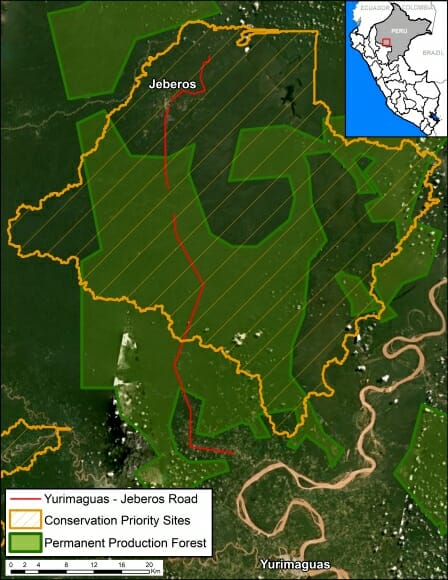

In addition, most of the route crosses “Permanent Production Forest“, a legal land classification restricted to forestry activities, not agriculture or infrastructure (Image D). The route also crosses a regional conservation priority site (Image D).

It is important to note that the Regional Government of Loreto, which is promoting and financing the project, specifically said in a press statement that the road will “encourage the expansion of the agricultural and livestock frontier in this part of the region.” That phrase can be interpreted as frankly stating that the road will cause extensive deforestation. It is a particularly troubling scenario given that Yurimaguas is already a deforestation hotspot.

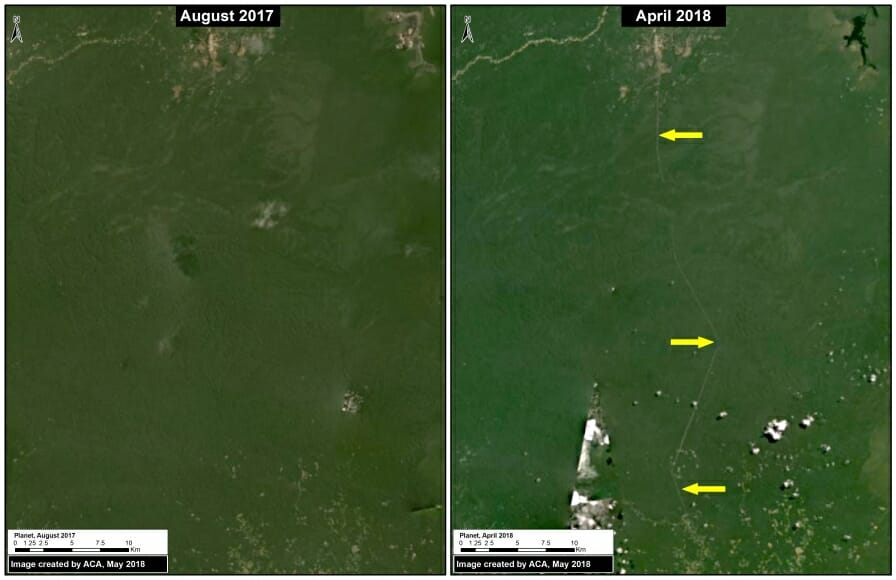

Image C shows the beginning of road construction between August 2017 (left panel) and April 2018 (right panel).

Image D shows how the road crosses Permanent Production Forest and a regional conservation priority site.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2018) New Threats to the Peruvian Amazon (Part 1: Yurimaguas-Jeberos Road). MAAP: 84.