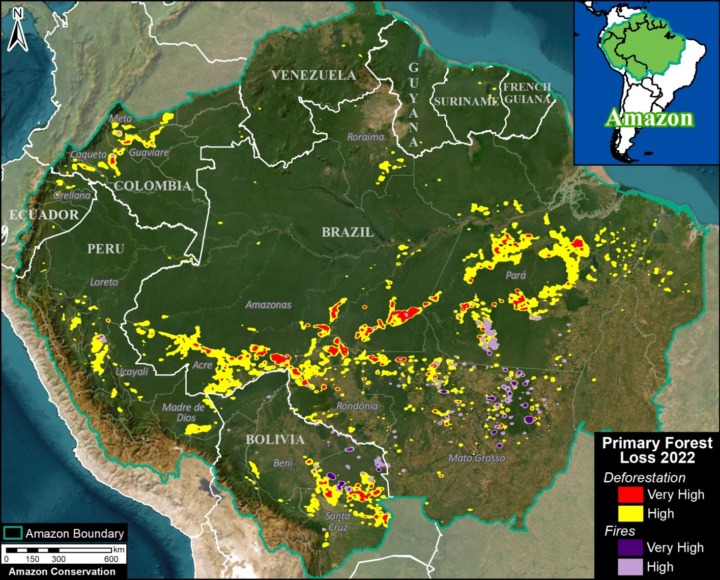

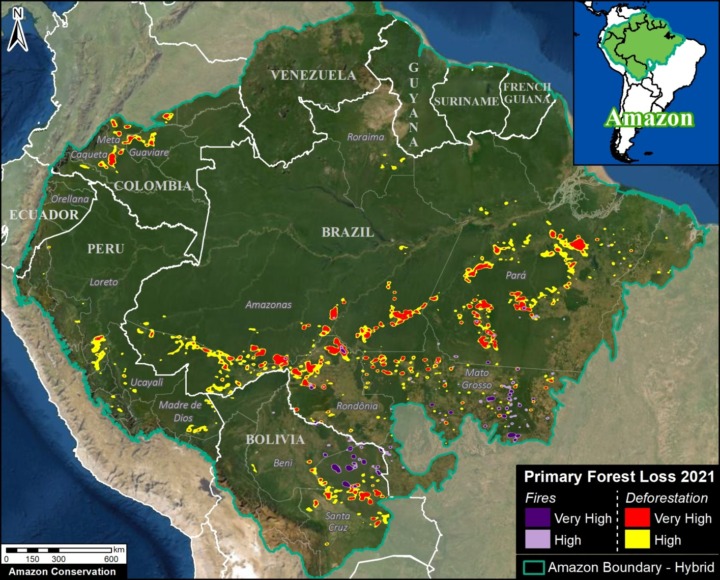

The Amazon fire season is well under way: to date, we have detected over 260 major fires thus far in 2023 (see Base Map below).

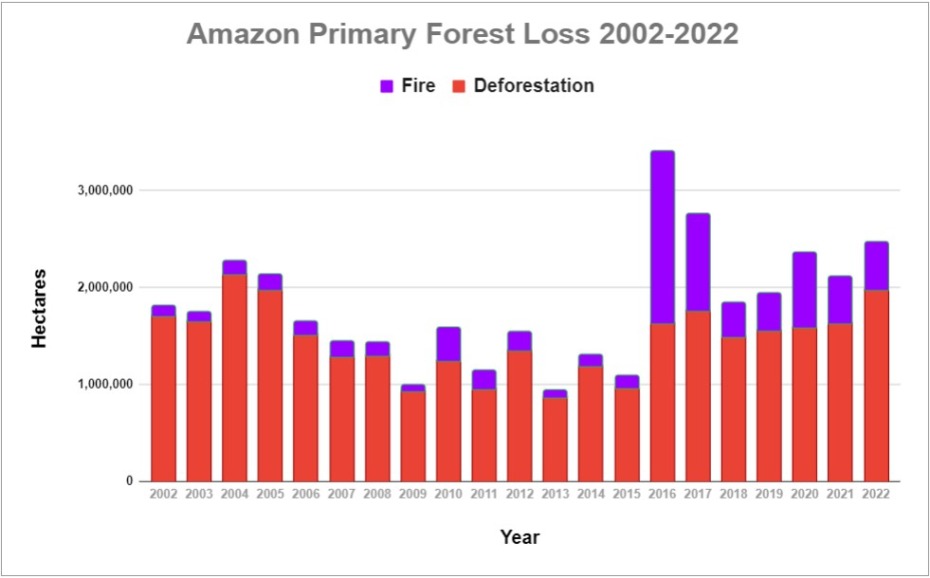

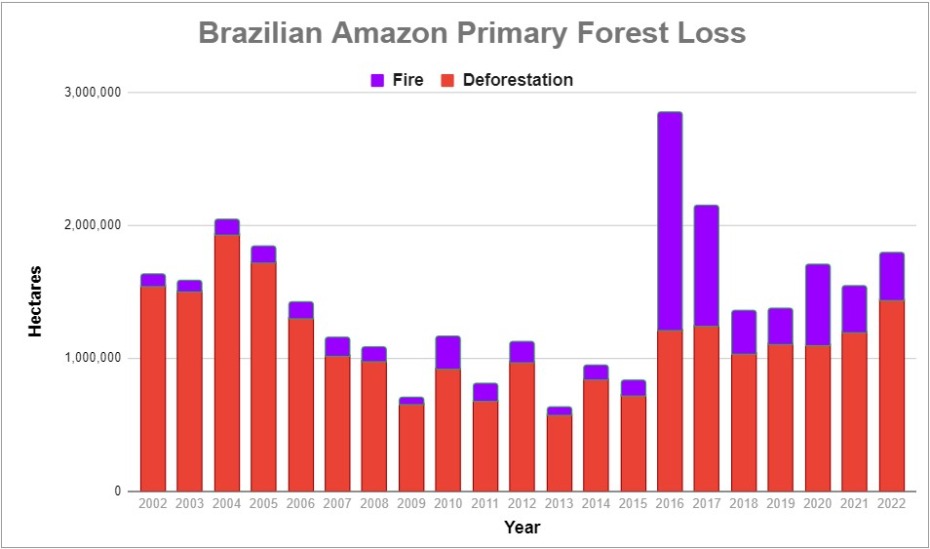

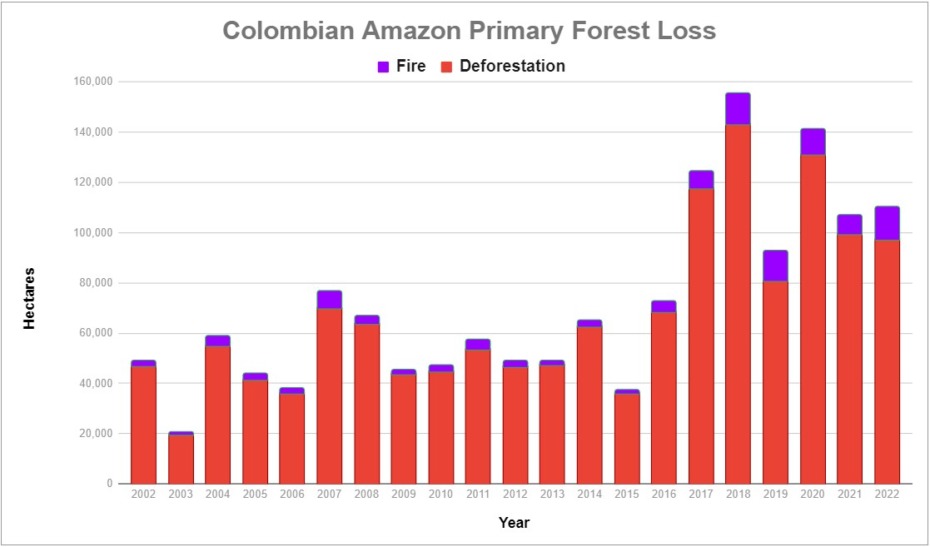

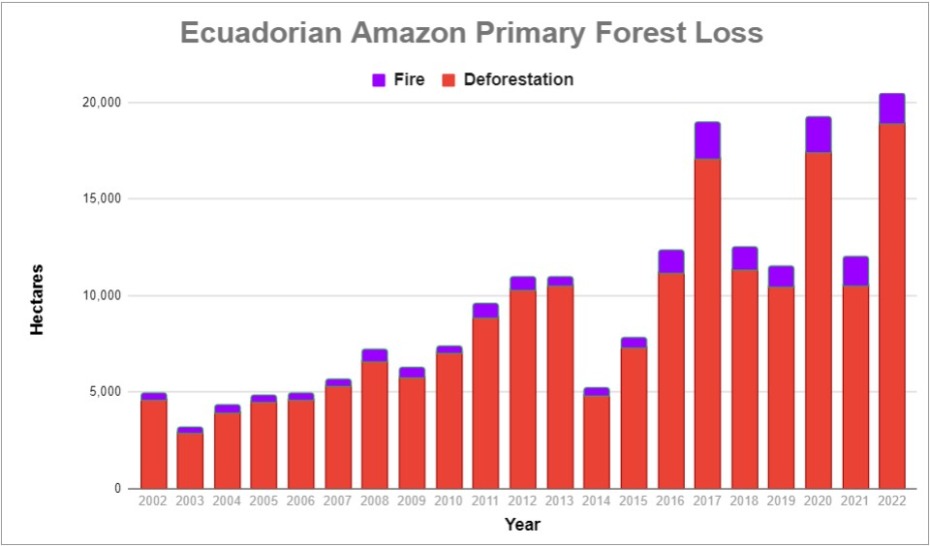

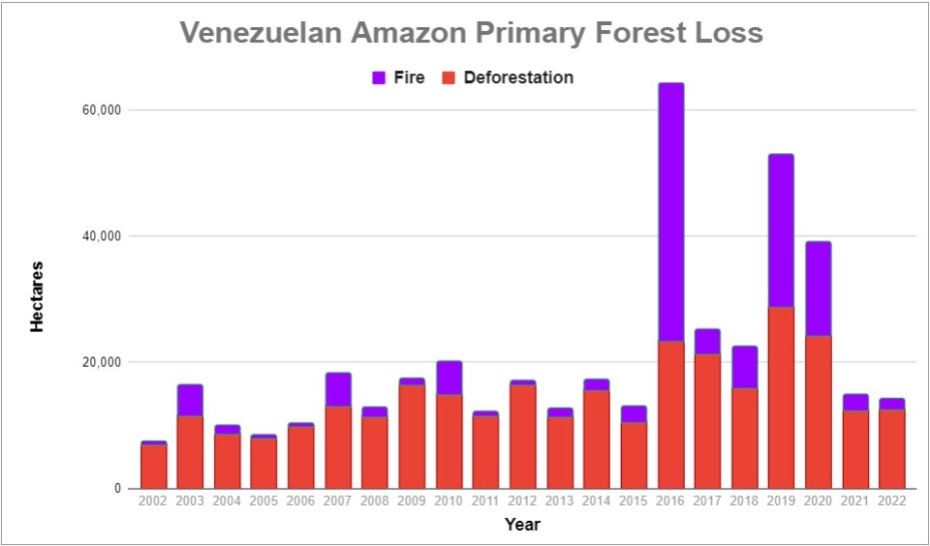

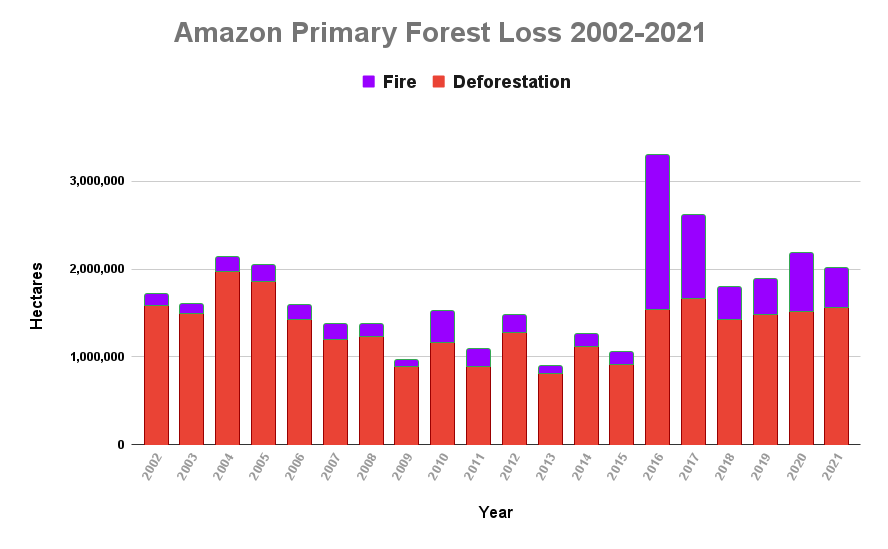

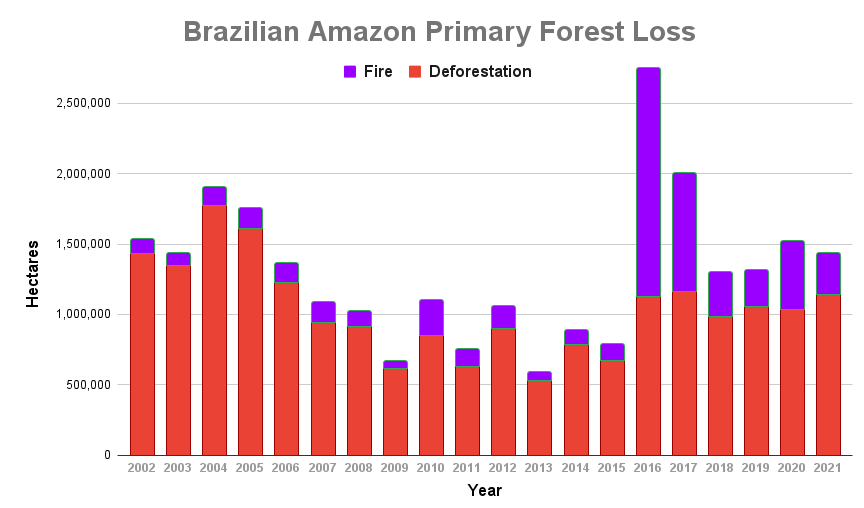

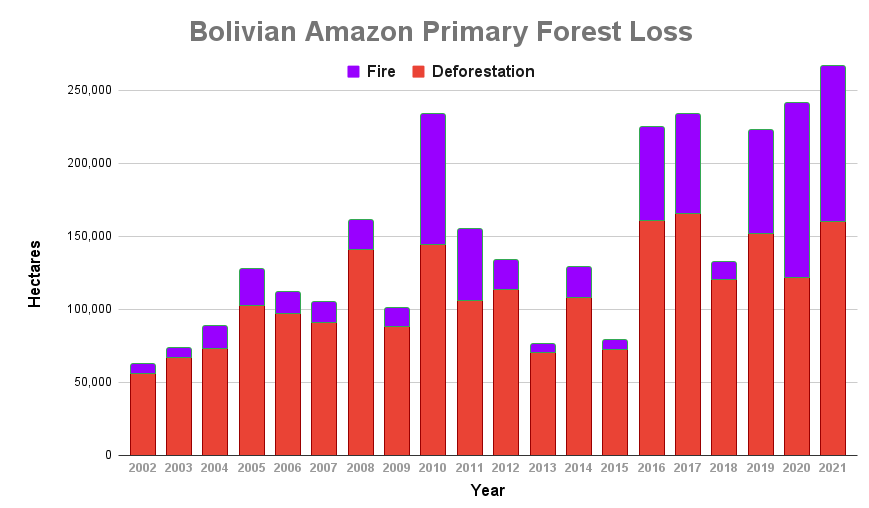

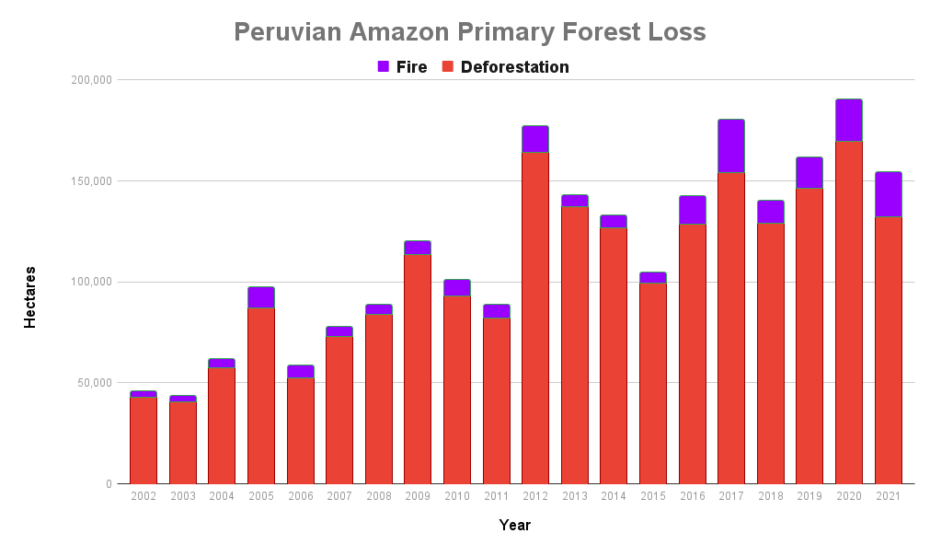

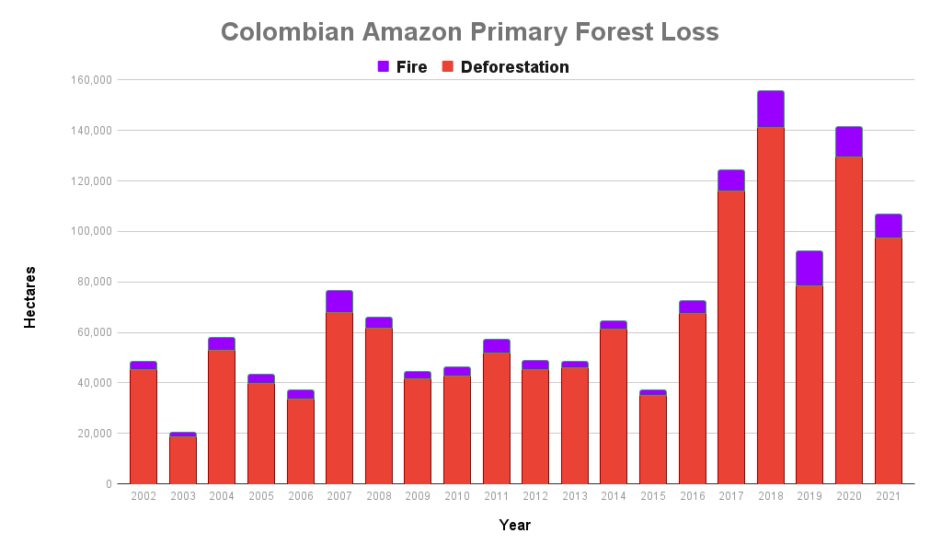

This year is of special concern because scientists indicate we have entered a new El Niño episode. The most intense Amazon fire seasons on record, 2016 and 2017, immediately followed the last major El Niño event.

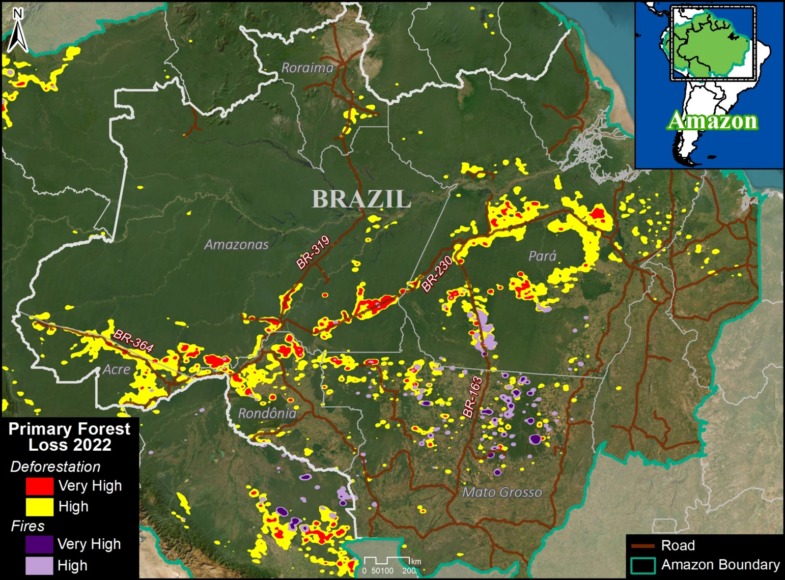

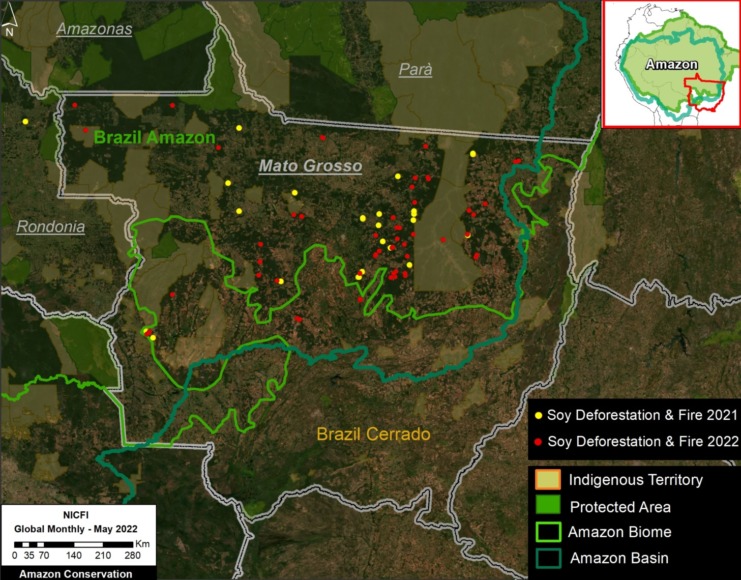

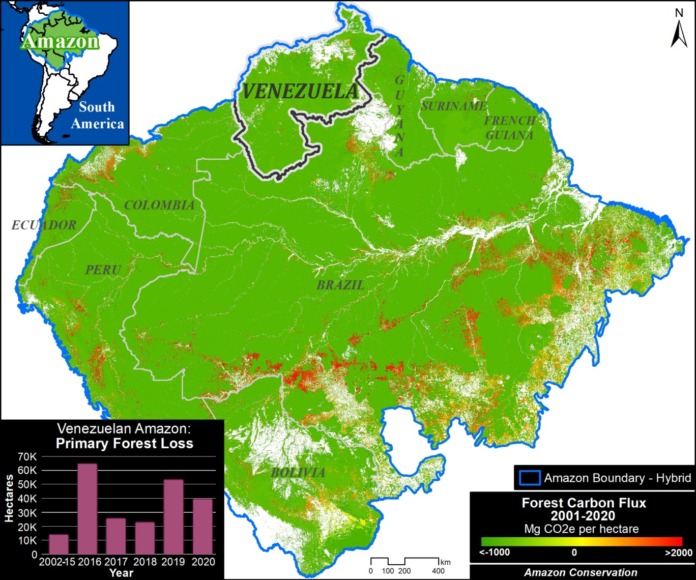

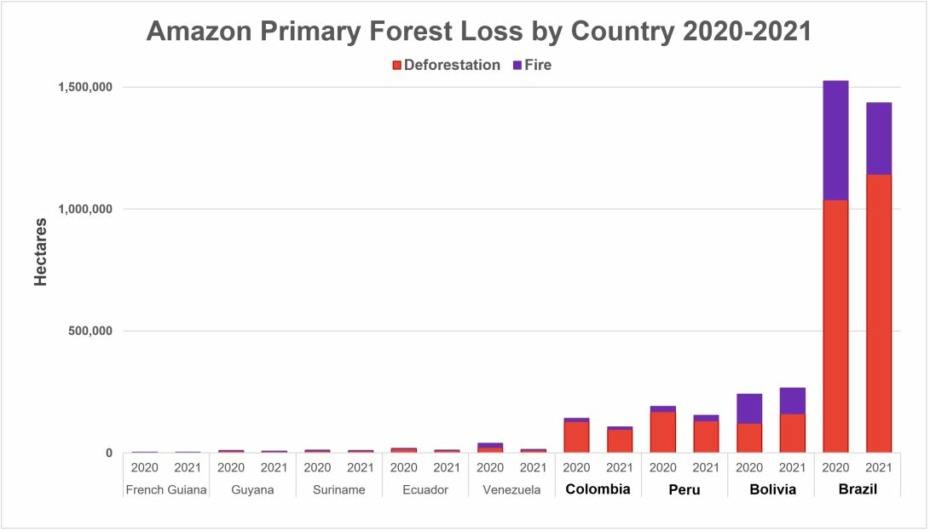

Most of the fires (54%) this year have occurred in the Brazilian Amazon.

Of these, the vast majority (73%) have burned recently deforested areas. This high number is consistent with previous years (see MAAP #168) and once again highlights the critical link between deforestation and fires in the Brazilian Amazon. That is, most major fires are burning the remnants of a recent deforestation event.

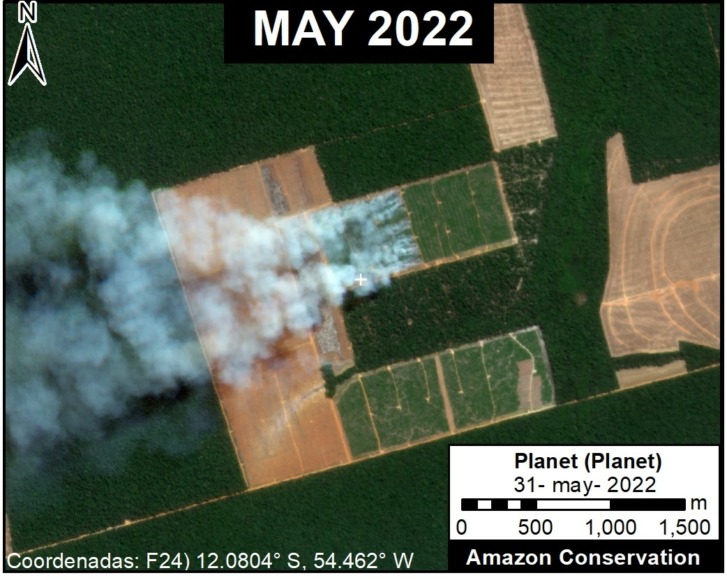

It is also worth noting that many of the fires in the Brazilian Amazon (42%) were burning areas recently deforested specifically for new soy plantations.

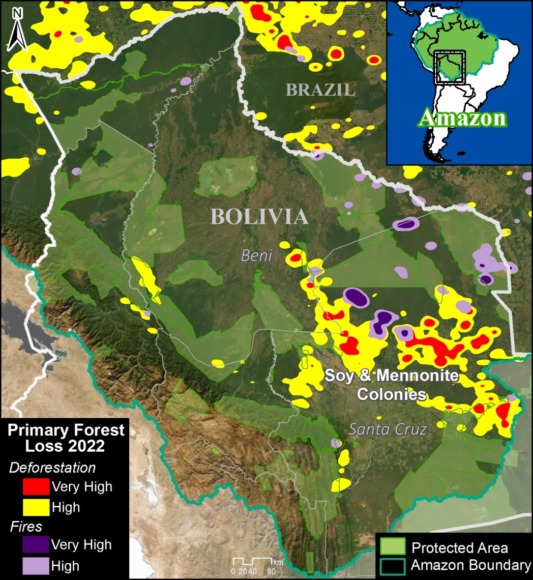

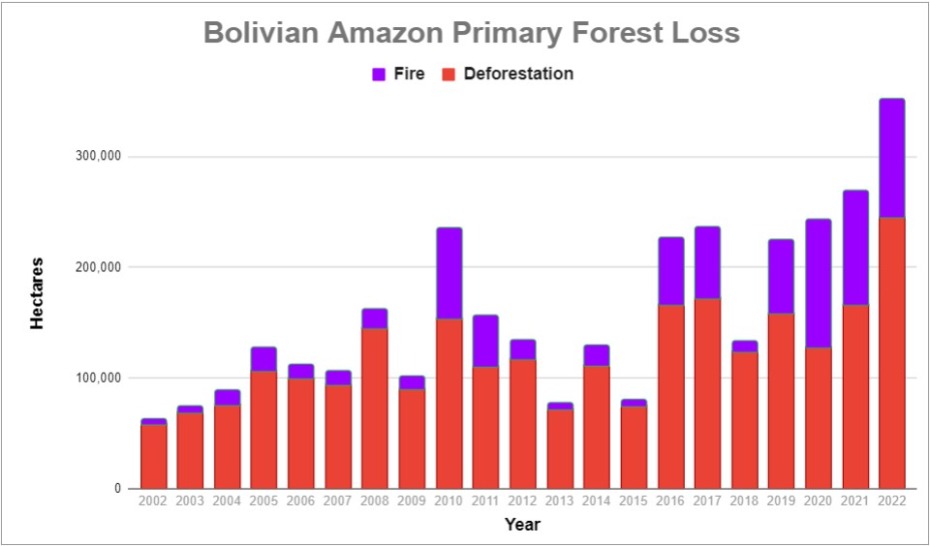

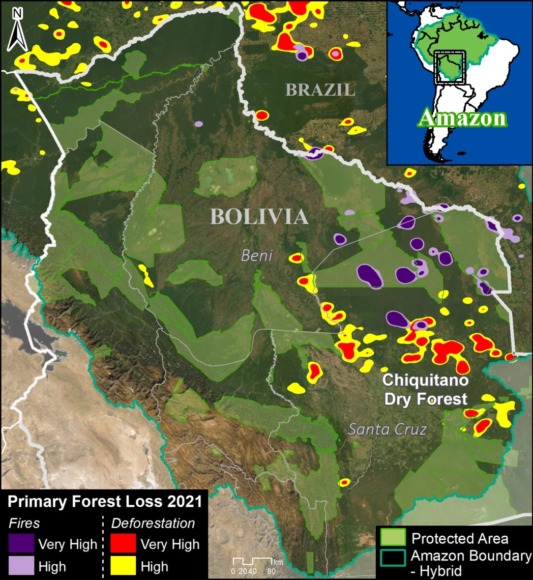

We have thus far detected 40 major fires in the Bolivian Amazon. The vast majority (88%) have been burning areas recently deforested specifically for new soy plantations.

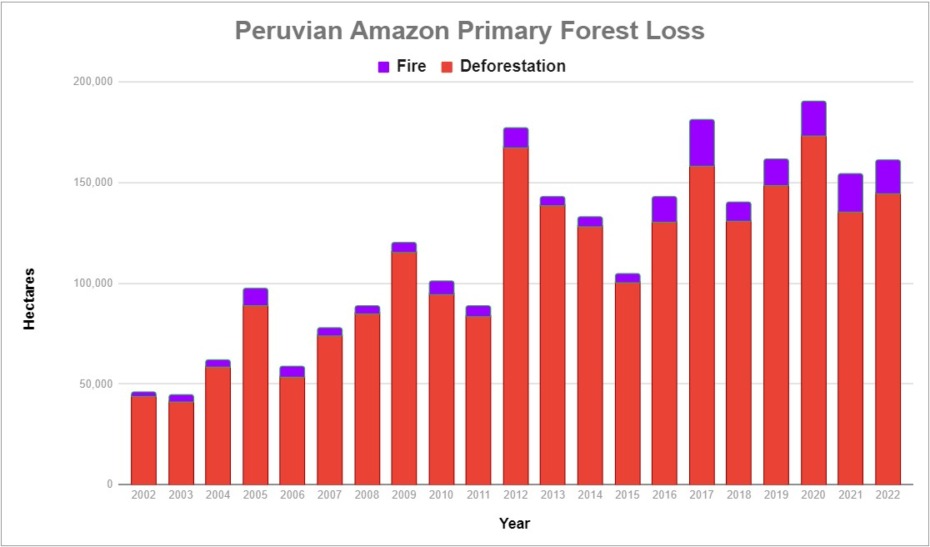

We have detected an additional 30 major fires in the Peruvian Amazon, mostly burning high elevation grasslands.

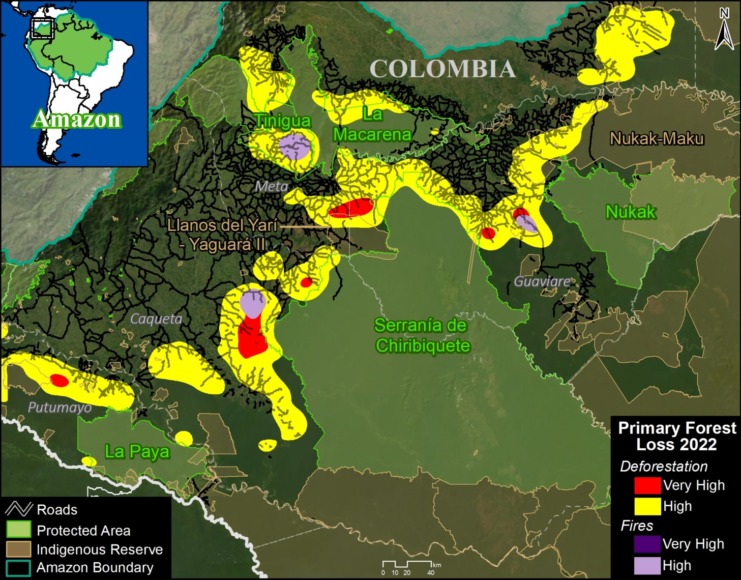

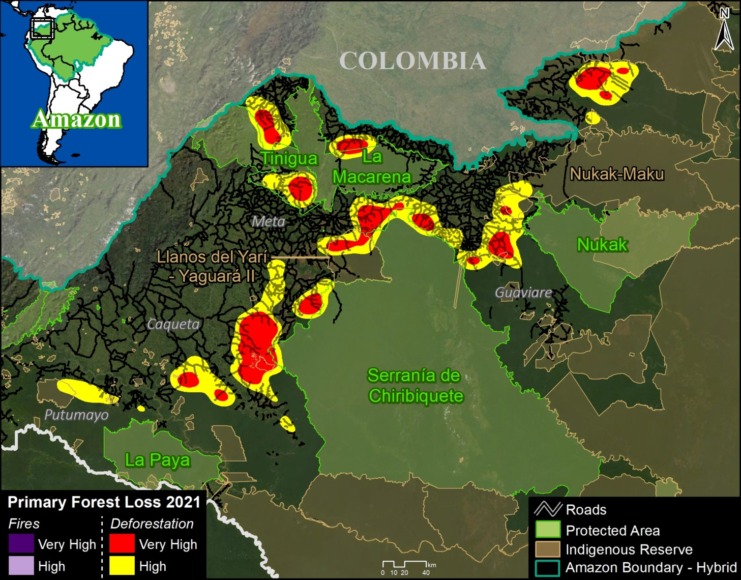

Earlier in the year, between January and March, we detected 50 major fires in the Colombian Amazon. Notably, 100% of them were in burning recently deforested areas.

These findings are based on the unique data from the real-time Amazon Fires Monitoring app developed by our partner organization in Peru, Conservación Amazónica ACCA. In a novel approach, the app combines data from the atmosphere (aerosol emissions in smoke) and the ground (heat anomaly alerts) to quickly and precisely detect major fires, defined as fires burning abundant biomass. In short, the app filters out smaller fires (such as routine burning an old field) and highlights major fires (such as burning recently deforested areas, standing forest, or natural grasslands).

2023 Major Amazon Fires Base Map

Amazon Fires Dashboard

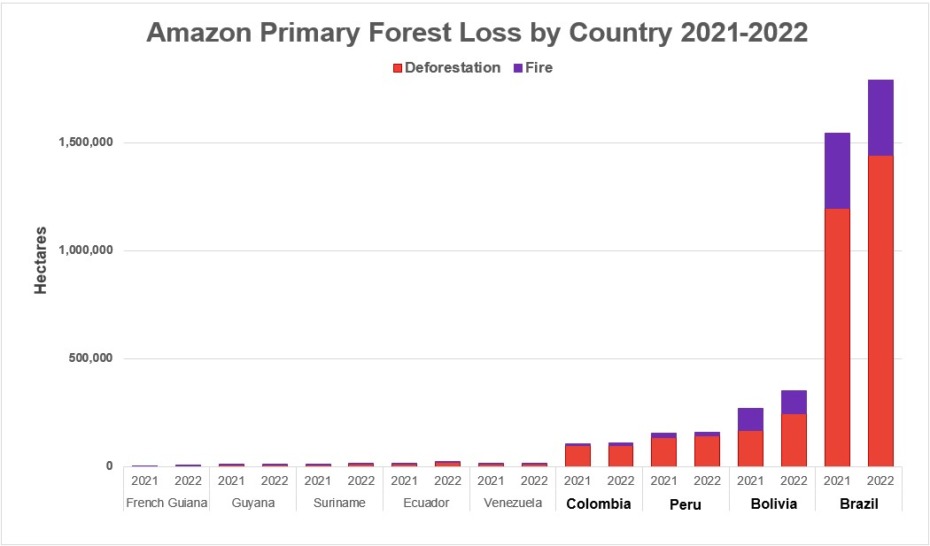

We also present our new Amazon fires dashboard, which currently shows results for the 2022 fire season. The dashboard highlights a number of the key findings from last year:

- We detected 983 major fires.

- The vast majority (72%) were in Brazil, followed by Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia.

- Importantly, 73% of the major fires burned recently deforested areas, followed by grasslands, forest fires, and pasture.

The dashboard was developed by the SAS Institute’s Data for Good Program.

Methodology

The reported results are based on an analysis of data generated by a unique real-time Amazon Fires Monitoring app during the year 2023, through July 13.

The app, hosted by Google Earth Engine, was developed and updated daily by the Peru-based organization Conservación Amazónica (ACCA). The resulting data was analyzed and recorded daily by the US-based organization Amazon Conservation. The app was created in 2019 and upgraded in 2020, with the current version launching in May 2021.

When fires burn, they emit gases and aerosols (aerosol definition: Suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in air or another gas) as part of the outgoing smoke. A relatively new satellite (Sentinel-5P from the European Space Agency) detects these aerosol emissions.

The aerosol data, which has a spatial resolution of 7.5 sq km, is not impacted by cloud cover, thus enabling near real-time monitoring during all weather conditions. The app is typically updated each day in the late afternoon/early evening with data for that same day. Thus, there is a high potential for authorities and civil society to also use this app to respond to major fires in the field.

Importantly, the app distinguishes small fires (such as from clearing old fields and thus burning little biomass) from larger fires (such as burning recently deforested areas or standing forests and thus burning high amounts of biomass).

We define a “major fire” as one showing elevated aerosol emission levels on the app, thus indicating the burning of elevated levels of biomass. This typically translates to an aerosol index (AI) of >1 (or cyan-green to red on the app).

In a novel approach, the app combines this aerosol data from the atmosphere with heat anomaly data from the ground.

For all detected major fires, we cross-referenced the aerosol emissions pattern with the ground heat-based data to pinpoint the exact location of the fire source. Typically for major fires, there is a large cluster of heat-anomaly alerts aiding the process.

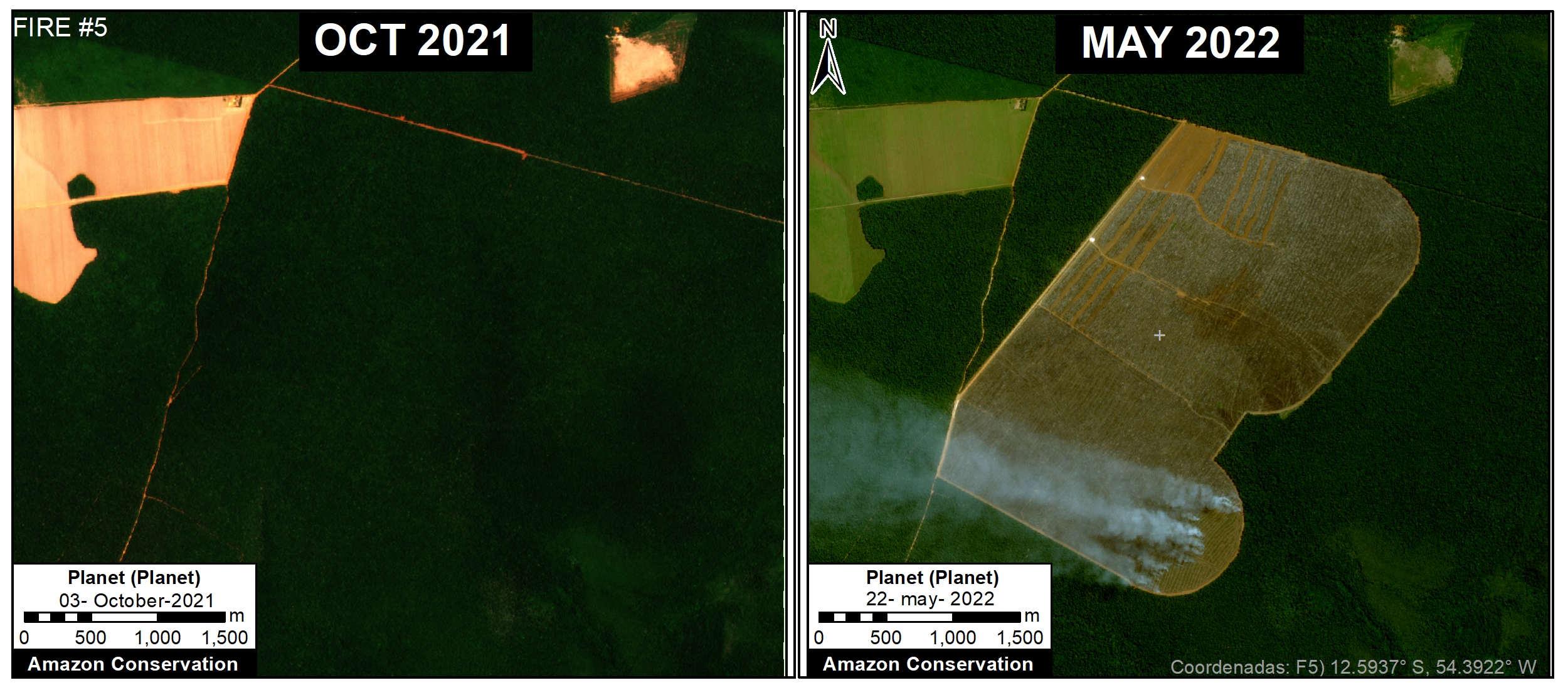

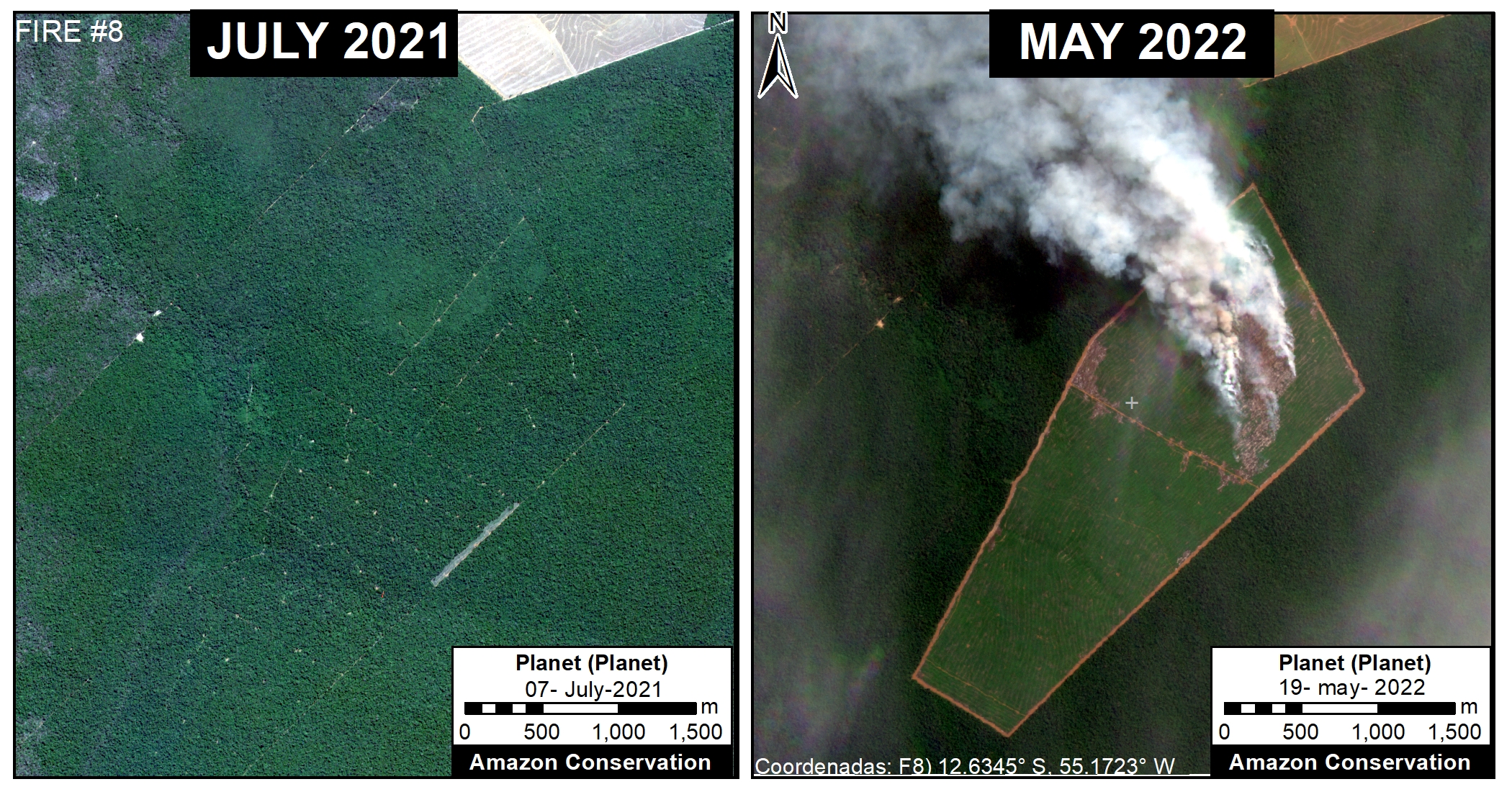

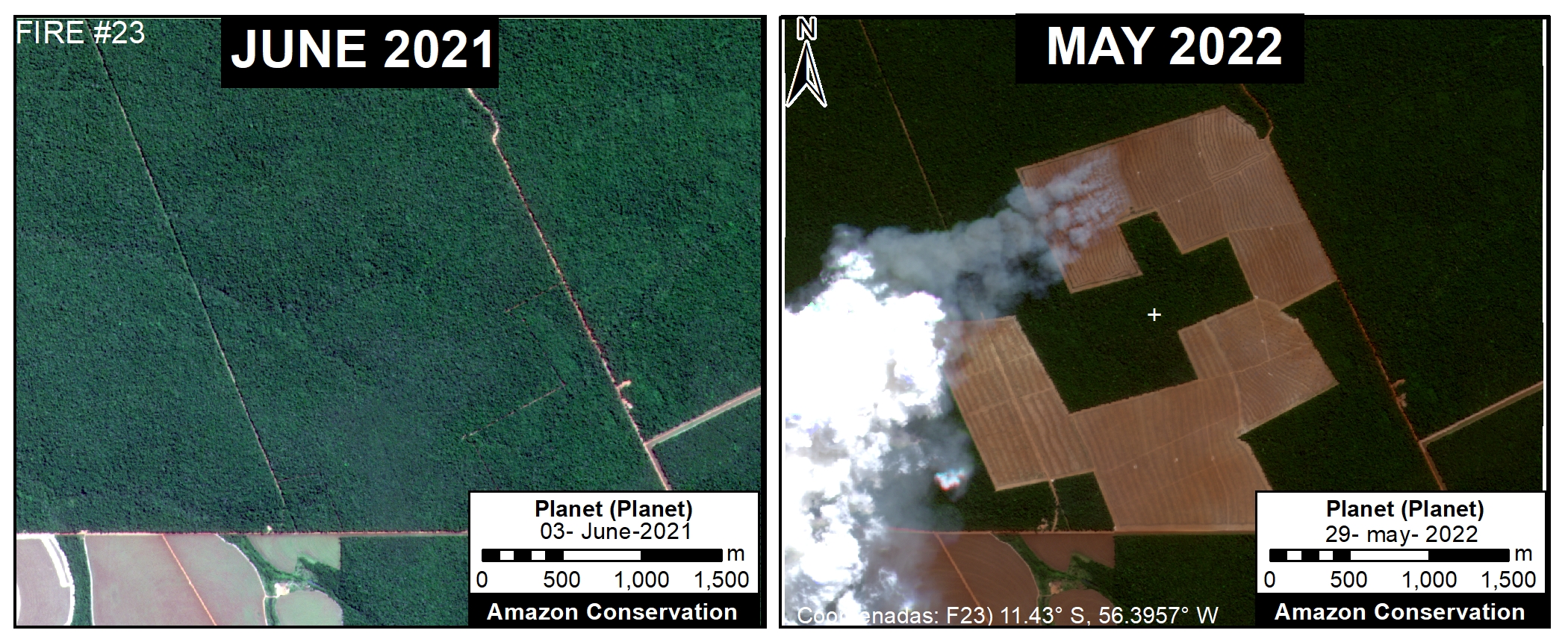

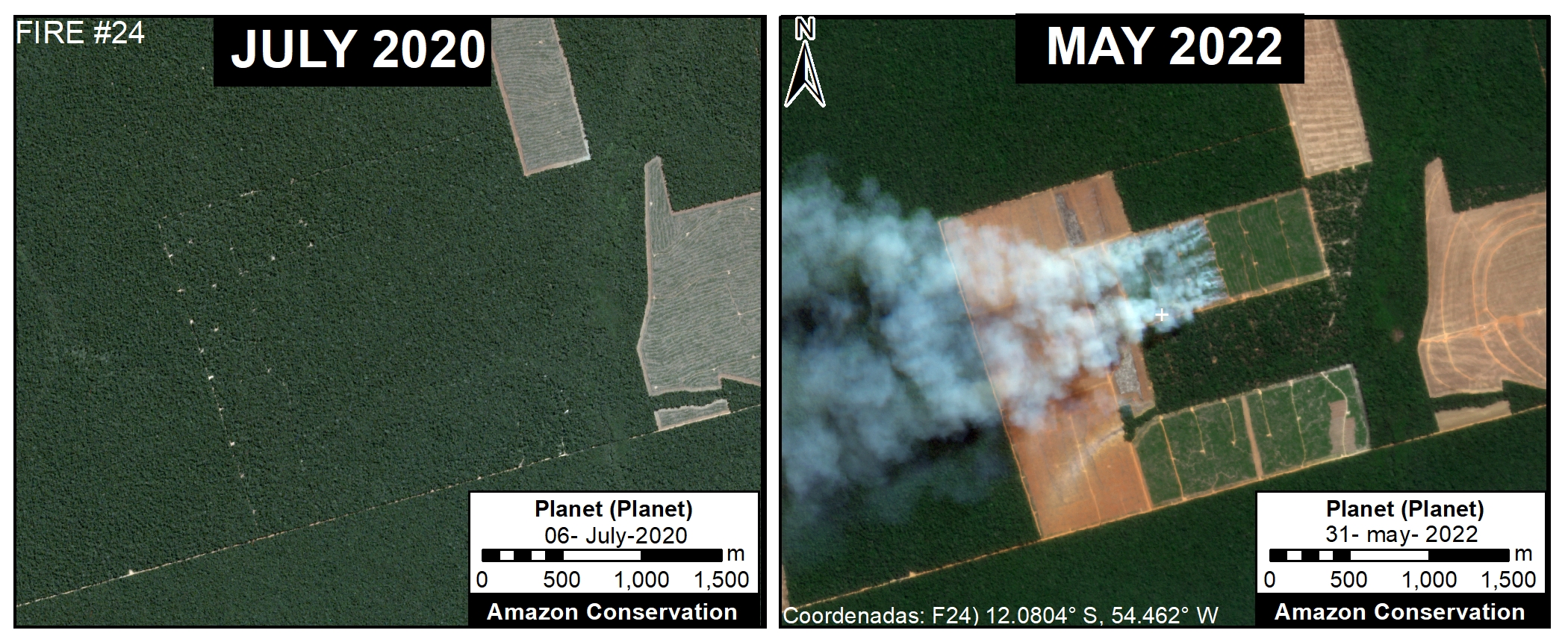

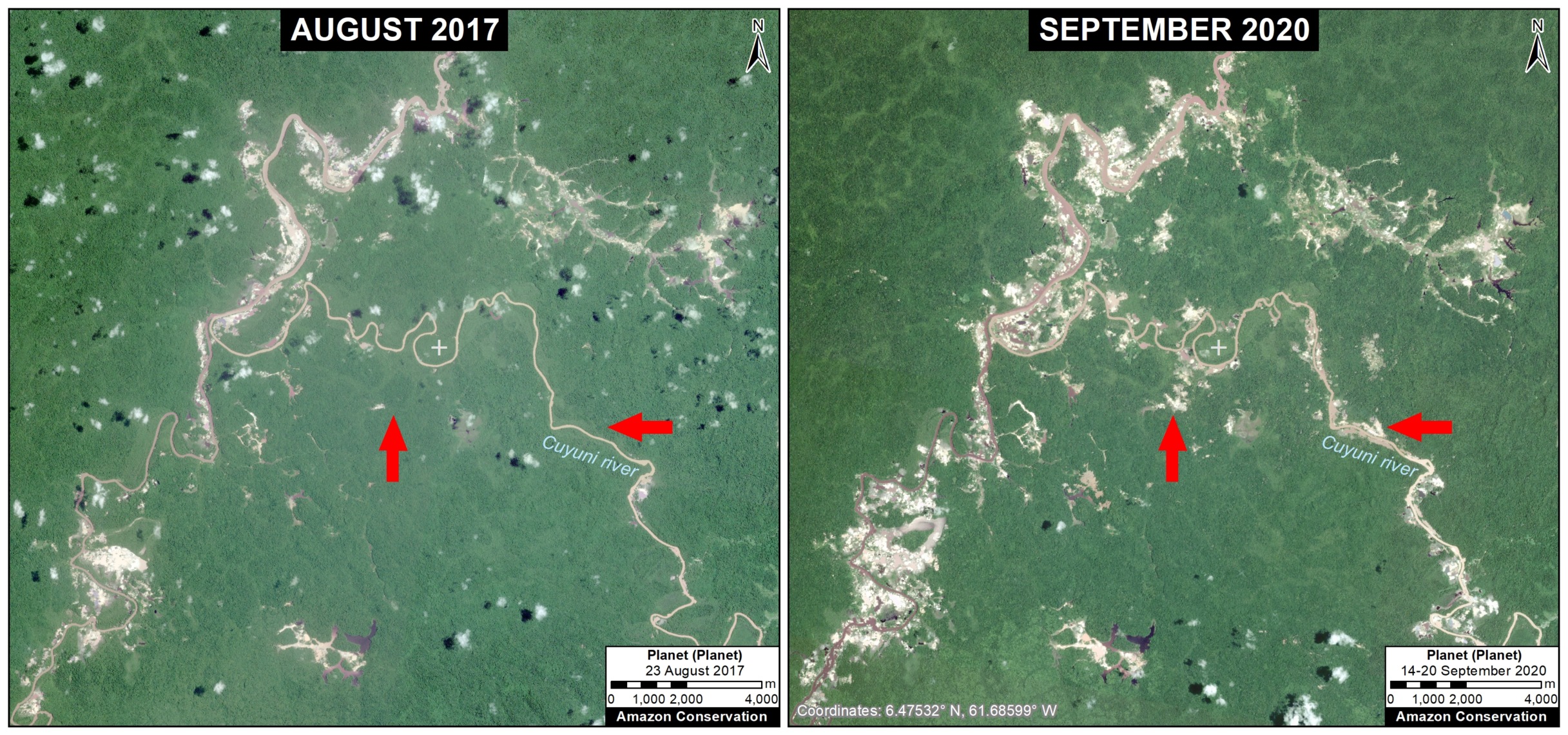

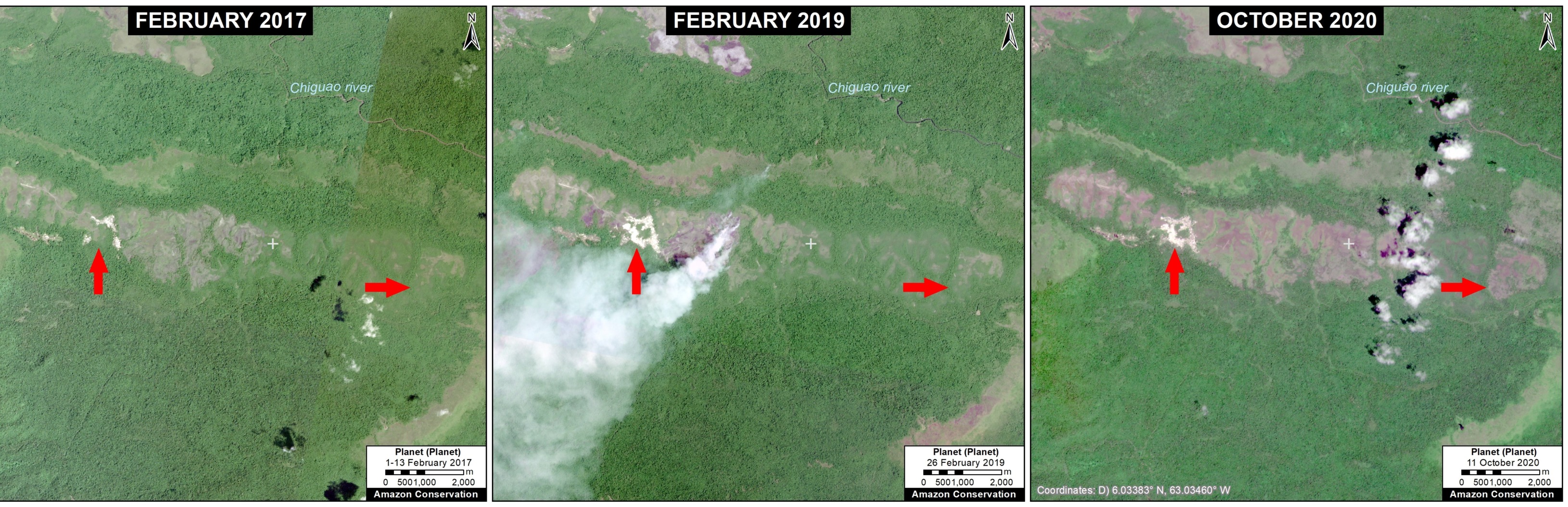

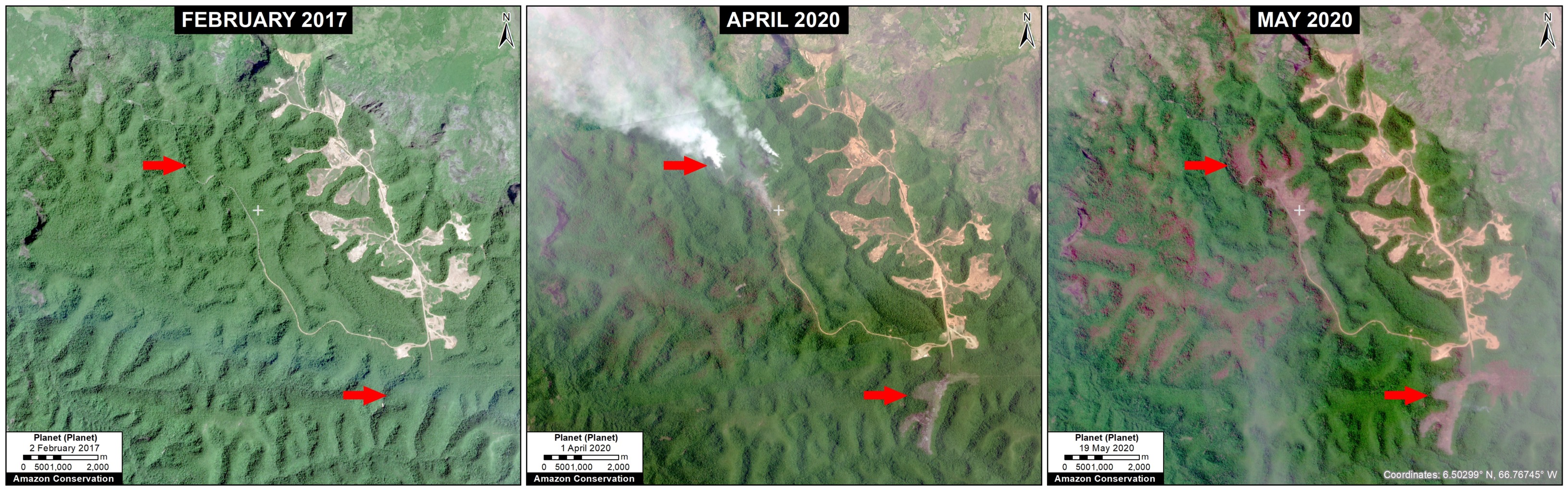

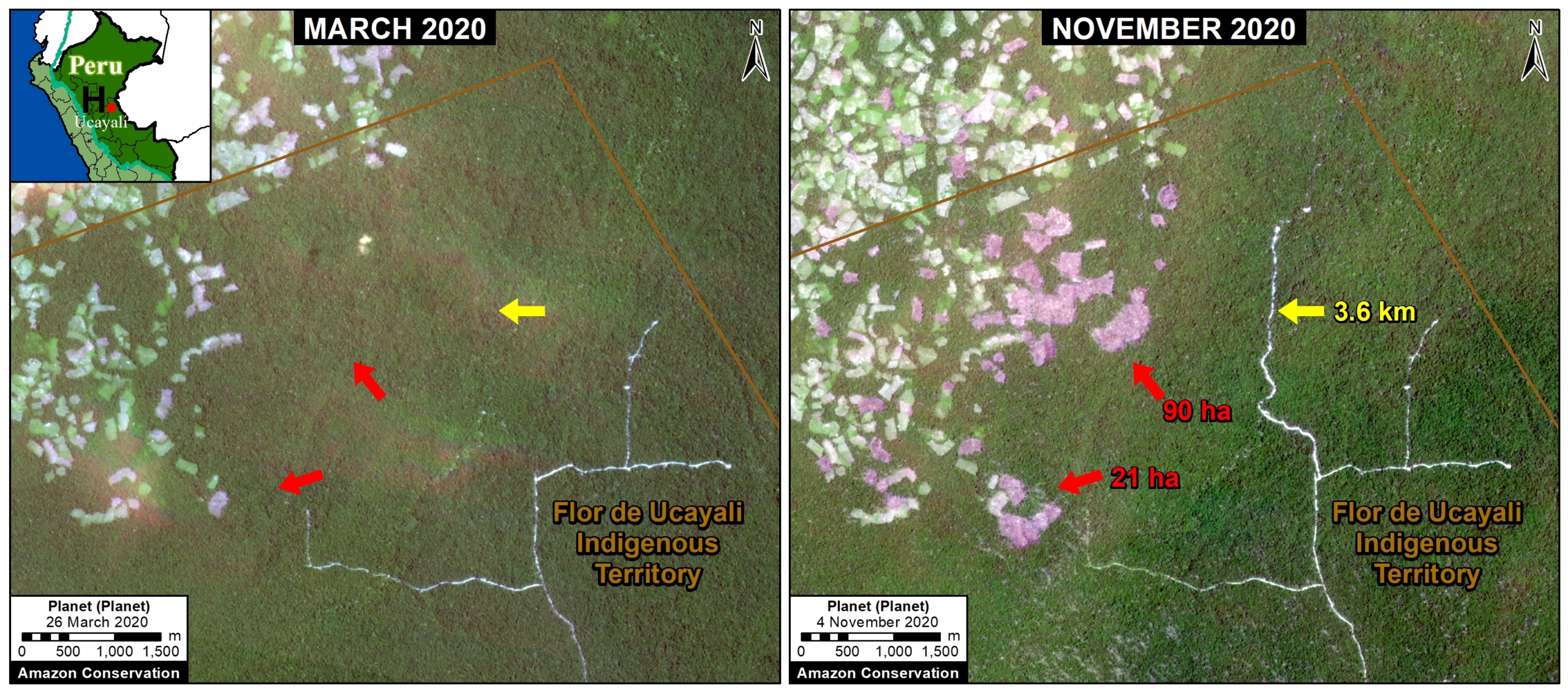

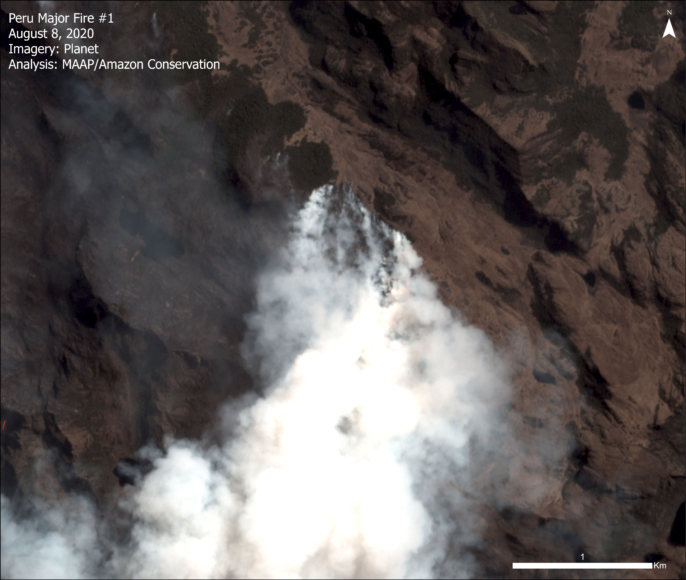

In a final step, the detected major fires are then analyzed with high-resolution optical satellite imagery from Planet Explorer. With this imagery, we can confirm the major fire (by observing smoke on the day of the fire or a burned area scar in the days following the fire) and estimate its size.

Moreover, with Planet’s extensive satellite imagery archive, we can determine the fire type. That is, by comparing imagery from the fire date to previous dates, we can determine whether the fire was burning a) a recently deforested area (defined as fires in areas recently deforested during the past three years), b) an older deforested area (typically long-standing pasture areas), c) standing forest (that is, a forest fire), or natural savannah.

In the app, we can also cross-reference if a major fire has occurred within a protected area or titled indigenous territory.

Note that the high values in the aerosol indices may also be due to other reasons such as emissions of volcanic ash or desert dust so it is important to cross-reference elevated emissions with heat data and optical imagery.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Norad (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) and ICFC (International Conservation Fund of Canada).

Citation

Finer M, Costa H, Villa L (2023) Amazon Fire Season Heats Up. MAAP: 189.