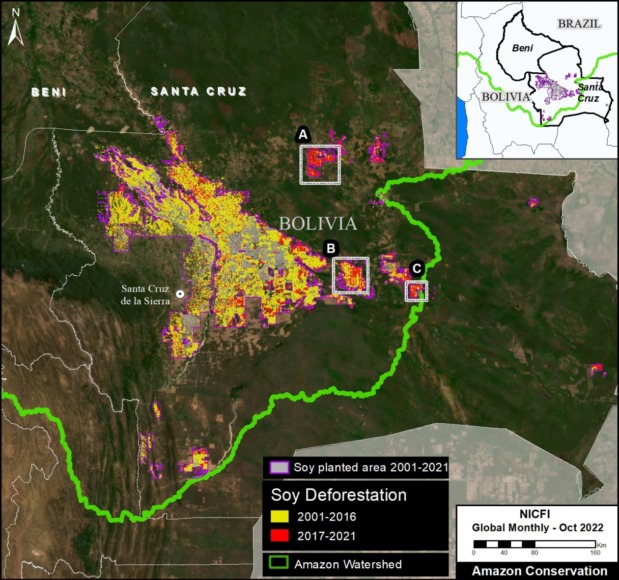

A burst of new data and online visualization tools are revealing key land use patterns across the Amazon, particularly regarding the critical topic of agriculture. This type of data is particularly important because agriculture is the leading cause of overall Amazonian deforestation.

These new datasets include:

- Crops. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), a leading agriculture and food systems research authority, recently launched the latest version of their innovative crop monitoring product, the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM).1 This latest version, developed with support from WRI’s Land & Carbon Lab, features spatial data for 46 crops, including soybean, oil palm, coffee, and cocoa. This data is mapped at 10-kilometer resolution across the Amazon and updated through 2020.2

j - Cattle pasture. The Atlas of Pastures,3 developed by the Federal University of Goiás, facilitates access to data regarding Brazilian cattle pastures generated by MapBiomas. This data is mapped at 30-kilometer resolution and updated through 2022. We use Collection 5 from Mapbiomas for the rest of the Amazonian countries.4

j - Gold mining. New mining data is included for additional context. Amazon Mining Watch uses machine learning to map open-pit gold mining.5 This data is mapped at 10-kilometer resolution across the Amazon and updated through 2023.

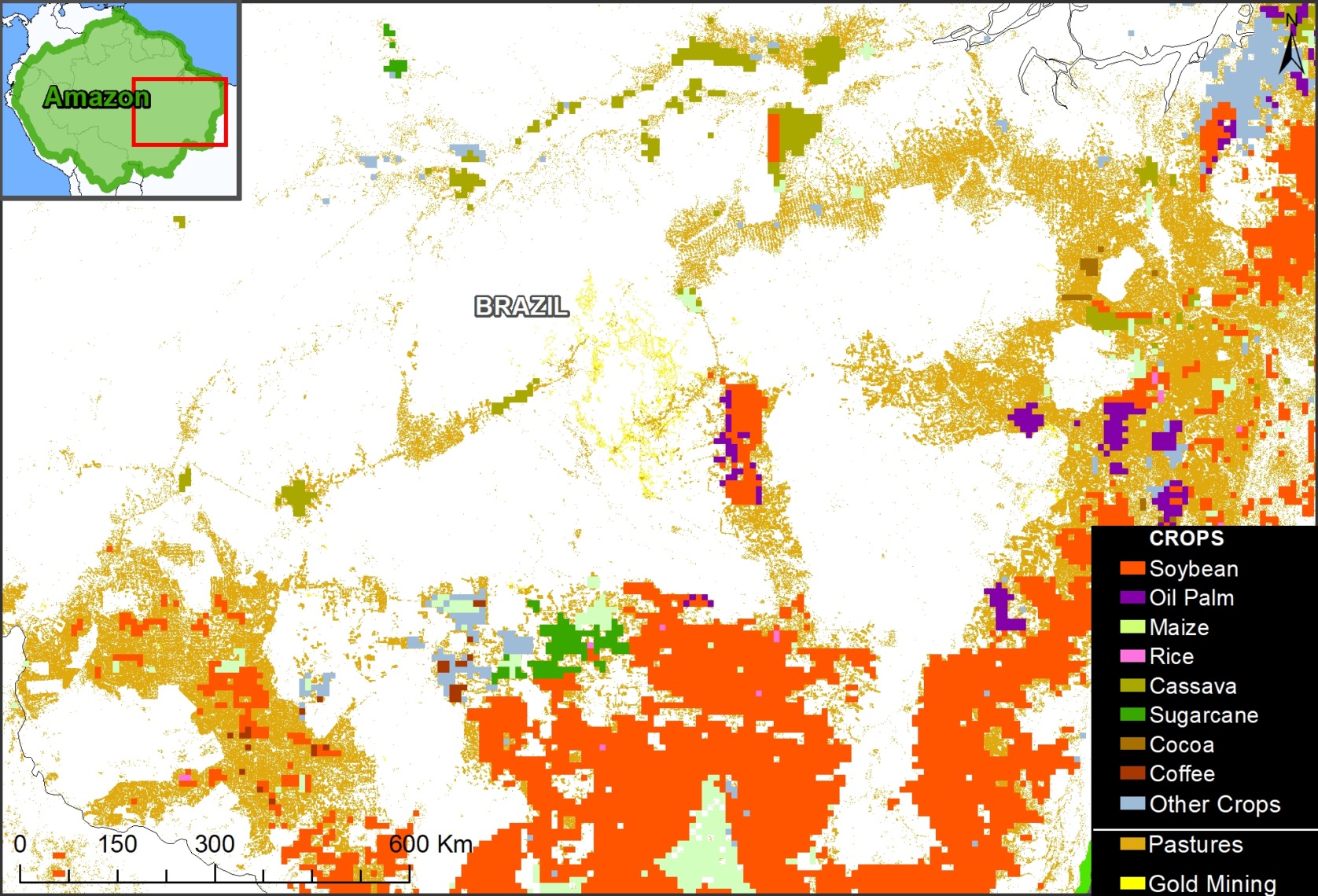

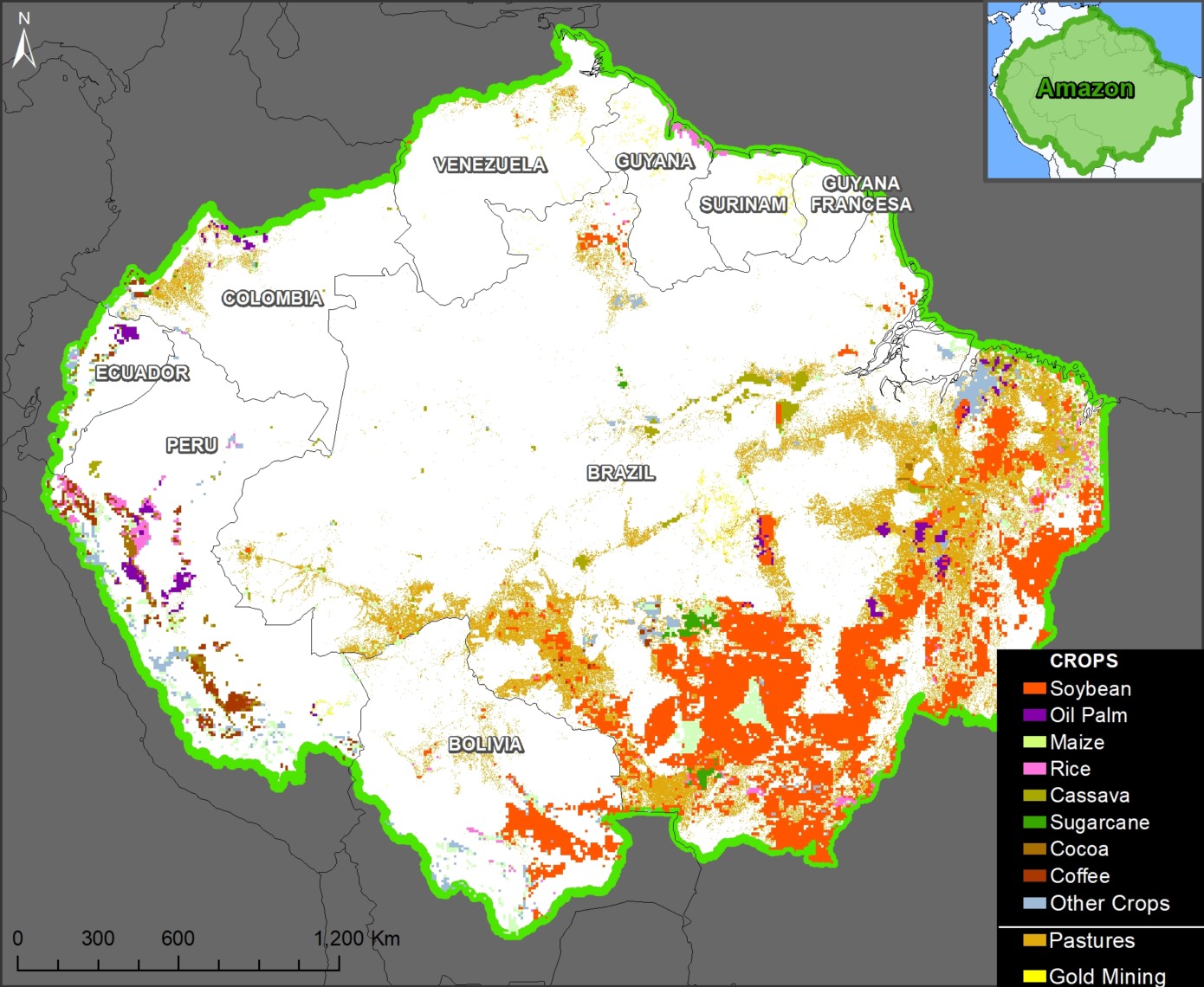

We merged and analyzed these new datasets to provide our first overall estimate of Amazonian land use, the most detailed effort to date across all nine countries of the biome. Figure 1 shows an example of this merged data in a section of the Brazilian Amazon.

Below, we present and illustrate the following major findings across the Amazon, and then zoom in on several regions across the Amazon to show the data in greater detail.

Major Findings

The Base Map illustrates several major findings detailed below.

1) Crops

We found that 40 crops in the SPAM dataset overlap with the Amazon, covering over 106 million hectares (13% of the Amazon biome).

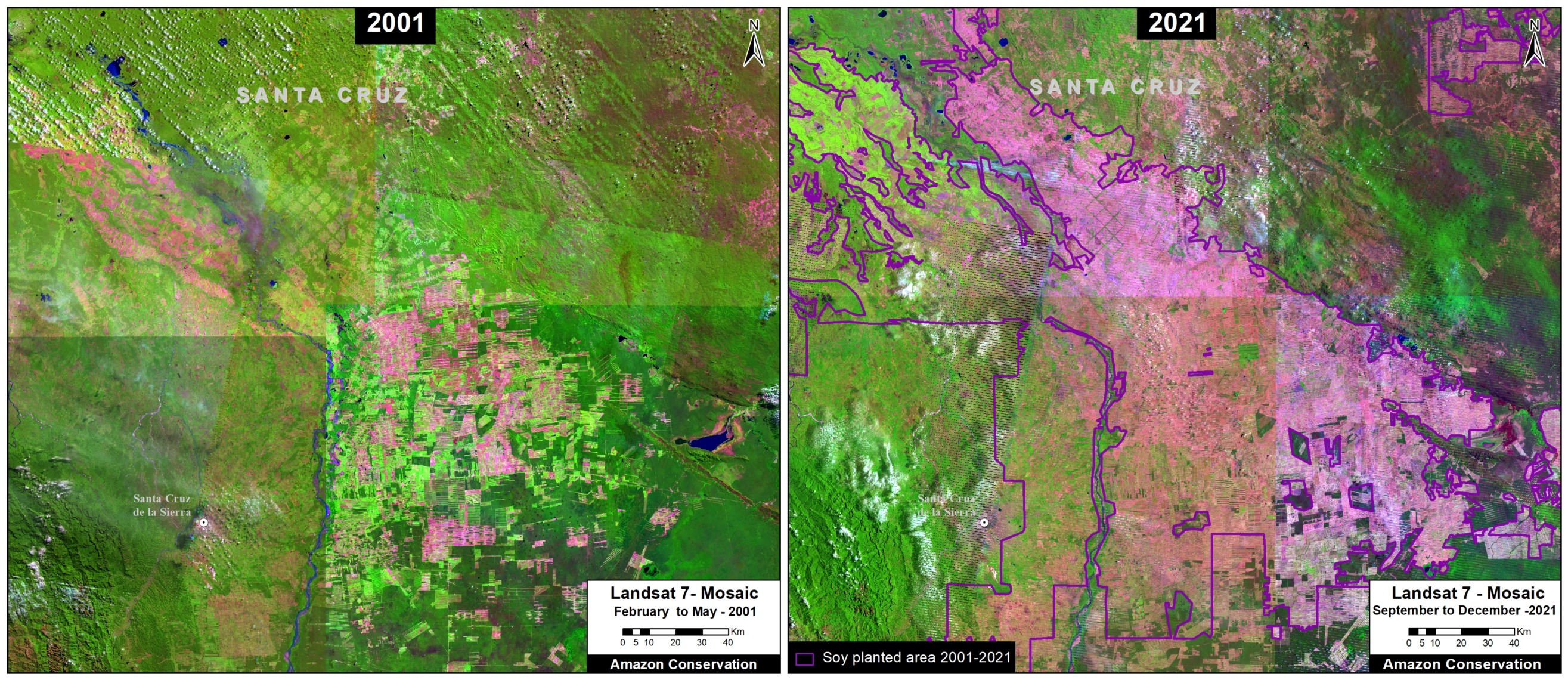

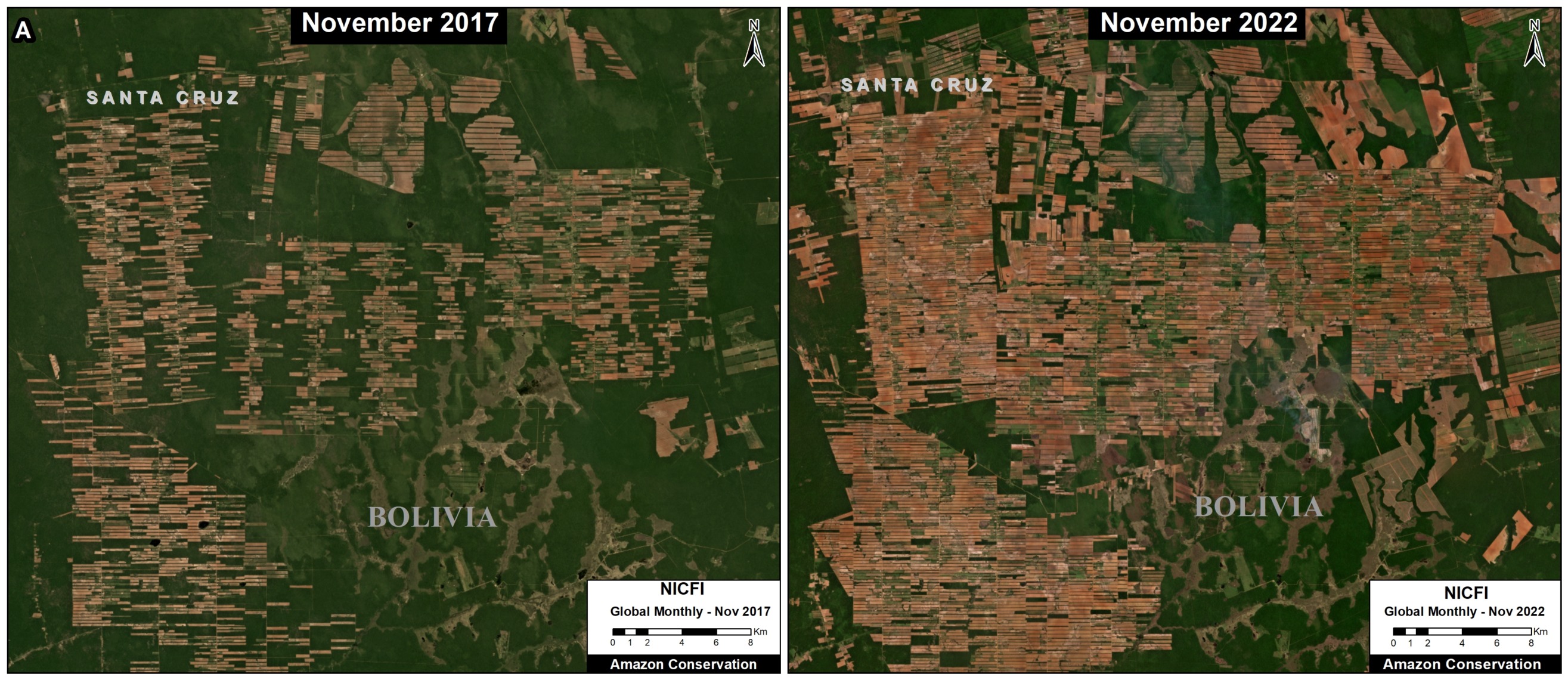

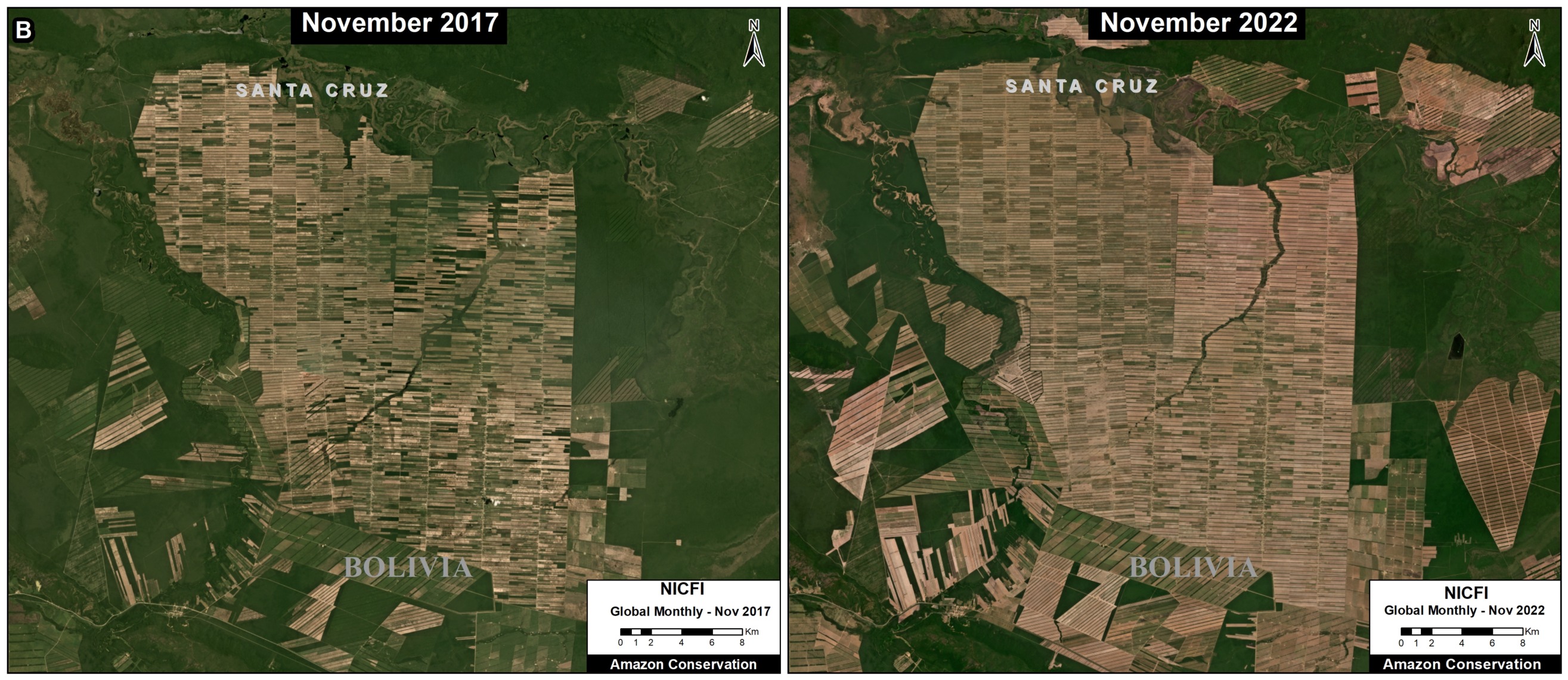

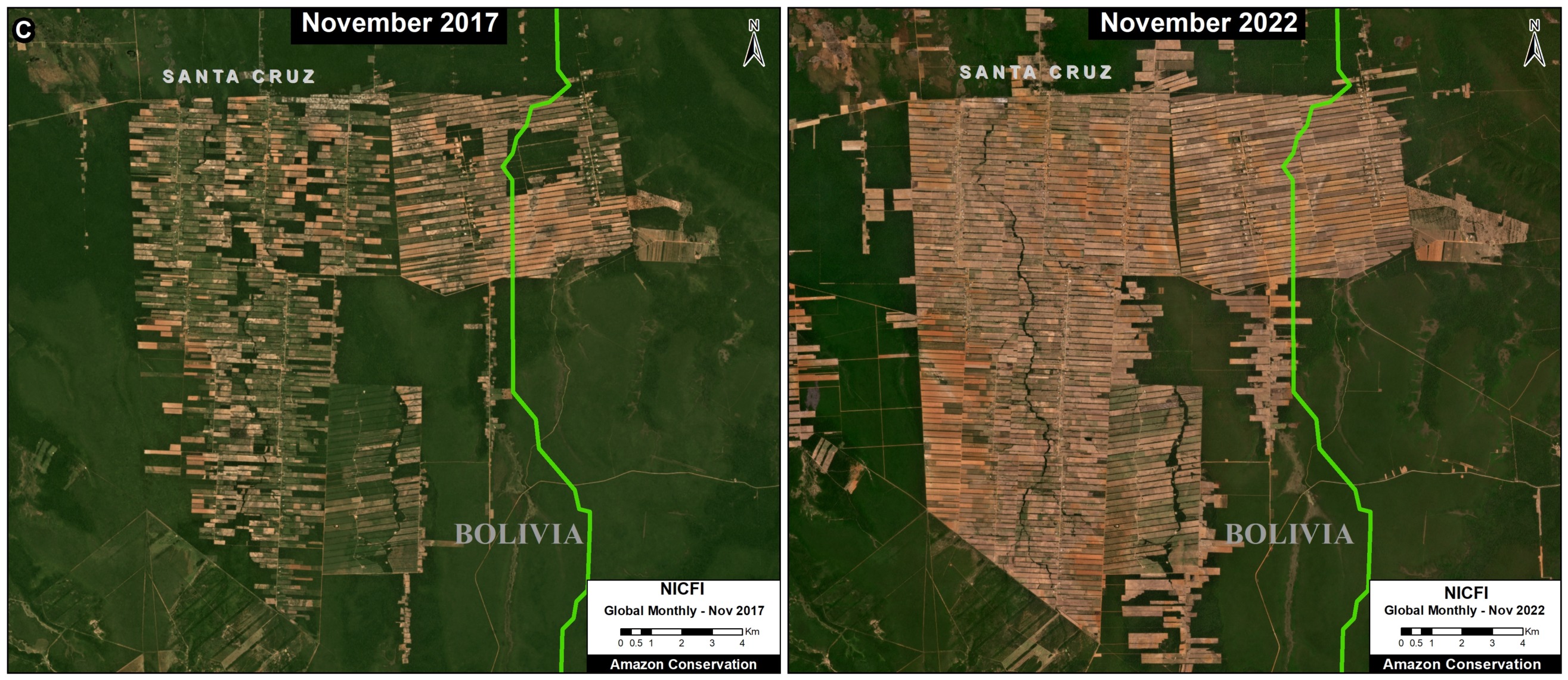

Soybean covers over 67.5 million hectares, mostly in southern Brazil and Bolivia. Maize covers slightly more area (70 million hectares) but we consider this a secondary rotational crop with soy (thus, there is considerable overlap between these two crops).

Oil palm covers nearly 8 million hectares, concentrated in eastern Brazil, central Peru, northern Ecuador, and northern Colombia.

In the Andean Amazon zones of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, cocoa covers over 8 million hectares and the two types of coffee (Arabica and Robusta) cover 6.7 million hectares.

Other major crops across the Amazon include rice (13.8 million hectares), sorghum (10.9 million hectares), cassava (9.8 million hectares), sugarcane (9.6 million hectares), and wheat (5.8 million hectares).

2) Cattle Pasture

Cattle Pasture covers 76.3 million hectares (9% of the Amazon biome). The vast majority (92%) of the pasture is in Brazil, followed by Colombia and Bolivia.

3) Crops & Cattle Pasture

Overall, accounting for overlaps between the data, we estimate that crops and pasture combined cover 115.8 million hectares. This total is the equivalent of 19% of the Amazon biome.

In comparison, open-pit gold mining covered 1.9 million hectares (0.23% of the Amazon biome).

Zooms across the Amazon

Eastern Brazilian Amazon

Figure 2 shows the transition from the soy frontier to the cattle pasture frontier in the eastern Brazilian Amazon. Also note a mix of other crops, such as oil palm, sugarcane, and cassava, and some gold mining.

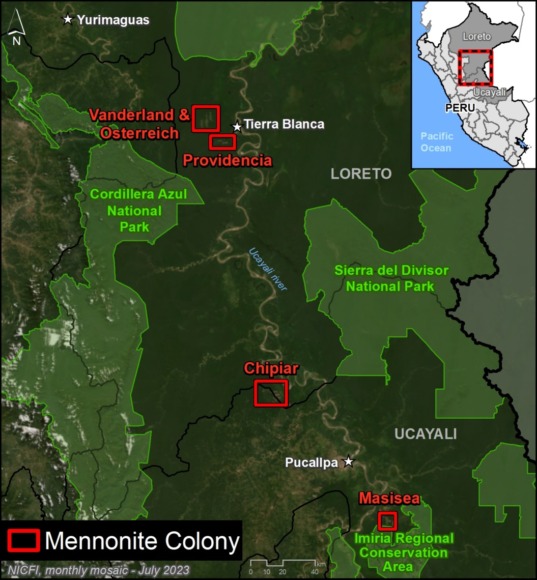

Andean Amazon (Peru and Ecuador)

The land use patterns are quite different in the Andean Amazon regions of Peru and Ecuador.

Figure 3 shows, that instead of soy and cattle pasture, there is instead oil palm, rice, coffee, and cocoa.

Also note the extension of the cattle pasture frontier in the western Brazilian Amazon, towards Peru and Bolivia.

Northeast Amazon (Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana)

Figure 4 shows the general lack of crops in the core Amazon regions Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, which is surely a major factor they are all considered High Forest cover, Low Deforestation countries (HFLD). In contrast, note there is abundant gold mining activity throughout this region.

Methods

For the SPAM data, we used the physical area, which is measured in a hectare and represents the actual area where a crop is grown (not counting how often production was harvested from it). We only considered values greater than or equal to 100 ha per pixel.

For the Base Map, due to their importance as primary economic crops, we layered soybean and oil palm as the top two layers, respectively. From there, crops were layered in order of their total physical area across the Amazon. Thus, the full extensions of some crops are not shown if they overlap pixels with other crops that have greater physical area. For overlaps with crops and pasture, we favored the crops.

Notes & Data Sources

1 International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 2024, “Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data for 2020 Version 1.0” https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SWPENT, Harvard Dataverse, V1

Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM)

SPAM 2020 v1.0 Global data (Updated 2024-04-16)

2 Note that the spatial resolution is rather low (10-kilometers) so all crop coverage data above should be interpreted as referential only.

3 The Atlas of Pastures (Atlas das Pastagens), open to the public, was developed by the Image Processing and Geoprocessing Laboratory of the Federal University of Goiás (Lapig/UFG), to facilitate access to results and products generated within the MapBiomas initiative, regarding Brazilian pastures.

https://atlasdaspastagens.ufg.br/

4 MapBiomas Collection 5; https://amazonia.mapbiomas.org/en/

5 See MAAP #212 for more information on Amazon Mining Watch.

Citation

Finer M, Ariñez A (2024) Agriculture in the Amazon: New data reveals key patterns of crops & cattle pasture. MAAP: 214.