tmp

MAAP #220: Carbon across the Amazon (part 3): Key Cases of Carbon Loss & Gain _alt

In part 1 of this series (MAAP #215), we introduced a critical new dataset (Planet’s Forest Carbon Diligence product) that provides wall-to-wall estimates for aboveground carbon at an unprecedented 30-meter resolution. This data uniquely merges machine learning, satellite imagery, airborne lasers, and a global biomass dataset from GEDI, a NASA mission.

In part 2 (MAAP #217), we highlighted which parts of the Amazon are currently home to the highest (peak) carbon levels.

Here in part 3, we focus on aboveground carbon loss and gain, presenting a novel Base Map that shows wall-to-wall estimates across the Amazon between 2013 and 2022.

Overall, we find that the Amazon still narrowly functions as an overall carbon sink, gaining 64.7 million metric tons of aboveground carbon between 2013 and 2022.1

The countries with the most carbon gain are 1) Brazil, 2) Colombia, 3) Suriname, 4) Guyana, and 5) French Guiana. In contrast, the countries with the most carbon loss are 1) Bolivia, 2) Venezuela, 3) Peru, and 4) Ecuador.

Zooming in to the site level yields additional important findings.

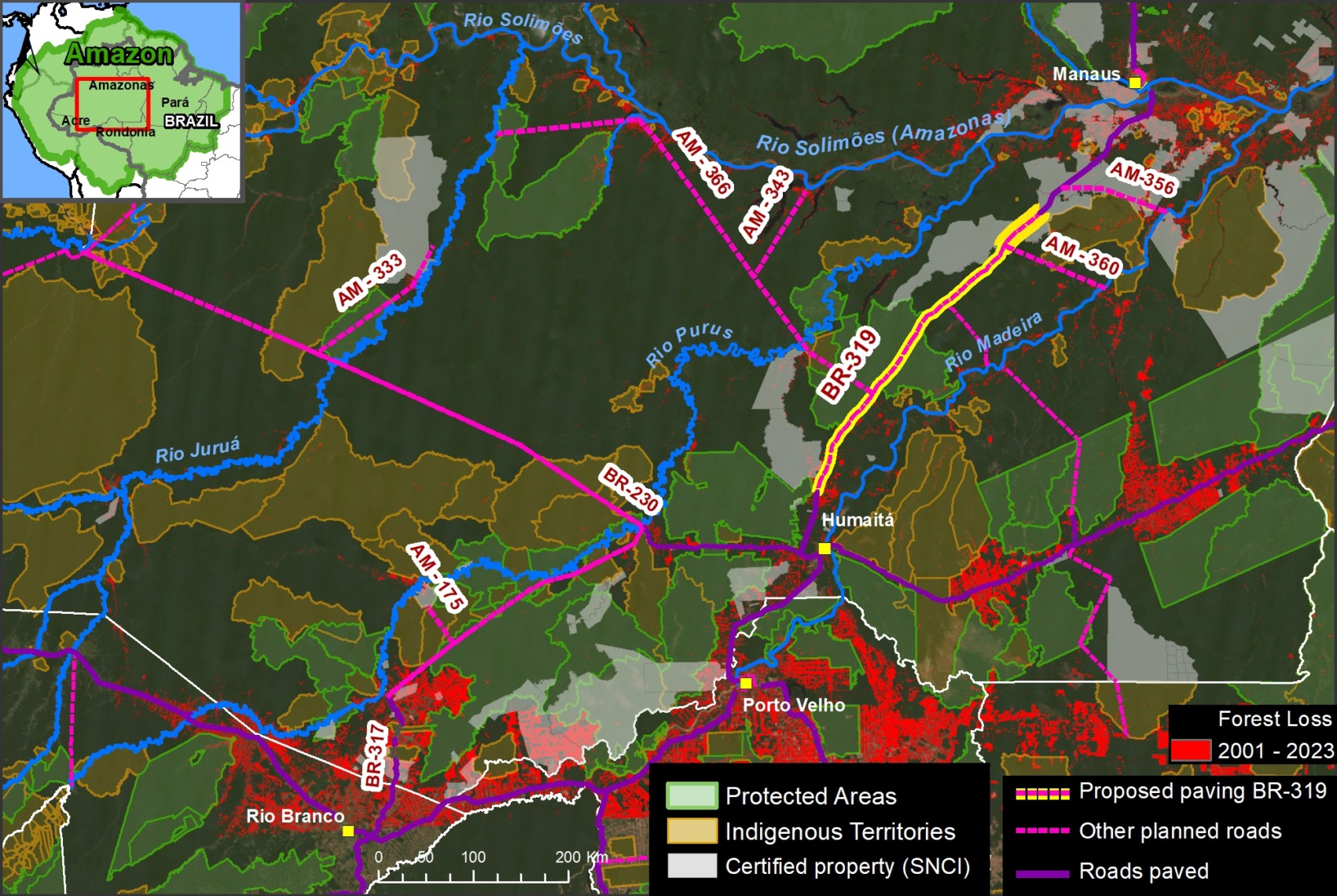

For example, areas with the highest carbon loss highlight emblematic deforestation cases across the Amazon during the past ten years (Figure 1).

On the flip side, areas with the highest carbon gain indicate excellent candidates for the High Integrity Forest (HIFOR) initiative, a new financing instrument that uniquely focuses on maintaining intact tropical forests.2 Importantly, a HIFOR unit represents a hectare of high integrity tropical forest that has been ‘well-conserved’ over a decade.3

Below, we further illustrate these findings with a series of zooms of emblematic cases of high carbon loss and gain across the Amazon over the past 10 years.

Figure 1. Example of major deforestation event resulting in high carbon emissions…

Base Map – Amazon Carbon Loss & Gain (2013-2022)

Base Map. Major areas of carbon loss and gain across the Amazon between 2013 and 2022.

The Base Map shows wall-to-wall estimates of aboveground carbon loss and gain across the Amazon between 2013 and 2022.

Carbon loss is indicated by yellow to red, indicating low to high carbon loss.

Note the extensive carbon loss across the arc of deforestation in Brazil, the soy plantation region in southern Bolivia, the gold mining region in southern Peru, and the other arc of deforestation in Colombia (see Insets A-E).

We also note that the areas of high carbon loss in the remote border area between Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela appear to be from natural causes, according to an additional review of satellite imagery.

Carbon gain is indicated by light to dark green, indicating low to high carbon gains.

Note that much of the Amazon functions as a carbon sink, with especially high carbon gain along the Ecuador-northern Peru border, eastern Colombia, western Brazil, and the northeast corner (Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana) (See Insets F-J).

Below, we present a series of zooms of the specific cases of high carbon loss and gain indicated in Insets A-J.

Emblematic Cases of Carbon Loss

Below we show a series…

A. Colombia National Parks (combine Tinigua, Macarena, north Chiribiquete)

B. Menonites Peru (just Vanderland area, not Chipiar)

C. Mining southern Peru

D – F. Best examples across Brazil

G. Suriname mining

Key Examples of Carbon Gain

Annex

In part 2 of this series (MAAP #217), we highlighted which parts of the Amazon are currently home to the highest (peak) aboveground carbon levels. Annex 1 shows these peak carbon areas in relation to the carbon loss and gain data presented above. Note that both peak carbon areas (southeast and northeast Amazon) are largely characterized by carbon gain.

Notes

1 In part 1 of this series (MAAP #215), we found the Amazon “is still functioning as a critical carbon sink”. As pointed out in a companion blog by Planet, however, the net carbon sink +64 million metric tons is quite small relative to the total estimate of 56.8 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon across the Amazon. That is a net positive change of just +0.1%. As the blog notes, that’s a “very small buffer” and there’s “reason to worry that the biome could flip from sink to source with ongoing deforestation.”

2 High Integrity Forest (HIFOR) units are a new tradable asset that recognizes and rewards the essential climate services and biodiversity conservation that intact tropical forests provide, including ongoing net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. HIFOR rewards the climate services that intact tropical forests provide, including ongoing net carbon removal from the atmosphere, and complements existing instruments to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+) by focusing on tropical forests that are largely undegraded. For more information see https://www.wcs.org/our-work/climate-change/forests-and-climate-change/hifor

3 High Integrity Forest Investment Initiative, Methodology for HIFOR units, April 2024. Downloaded from https://www.wcs.org/our-work/climate-change/forests-and-climate-change/hifor

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N, Anderson C, Rosenthal A (2024) Carbon across the Amazon (part 3): Key Cases of Carbon Loss & Gain. MAAP: 220.

MAAP #216: Uncontacted Indigenous group threatened by logging in the southern Peruvian Amazon

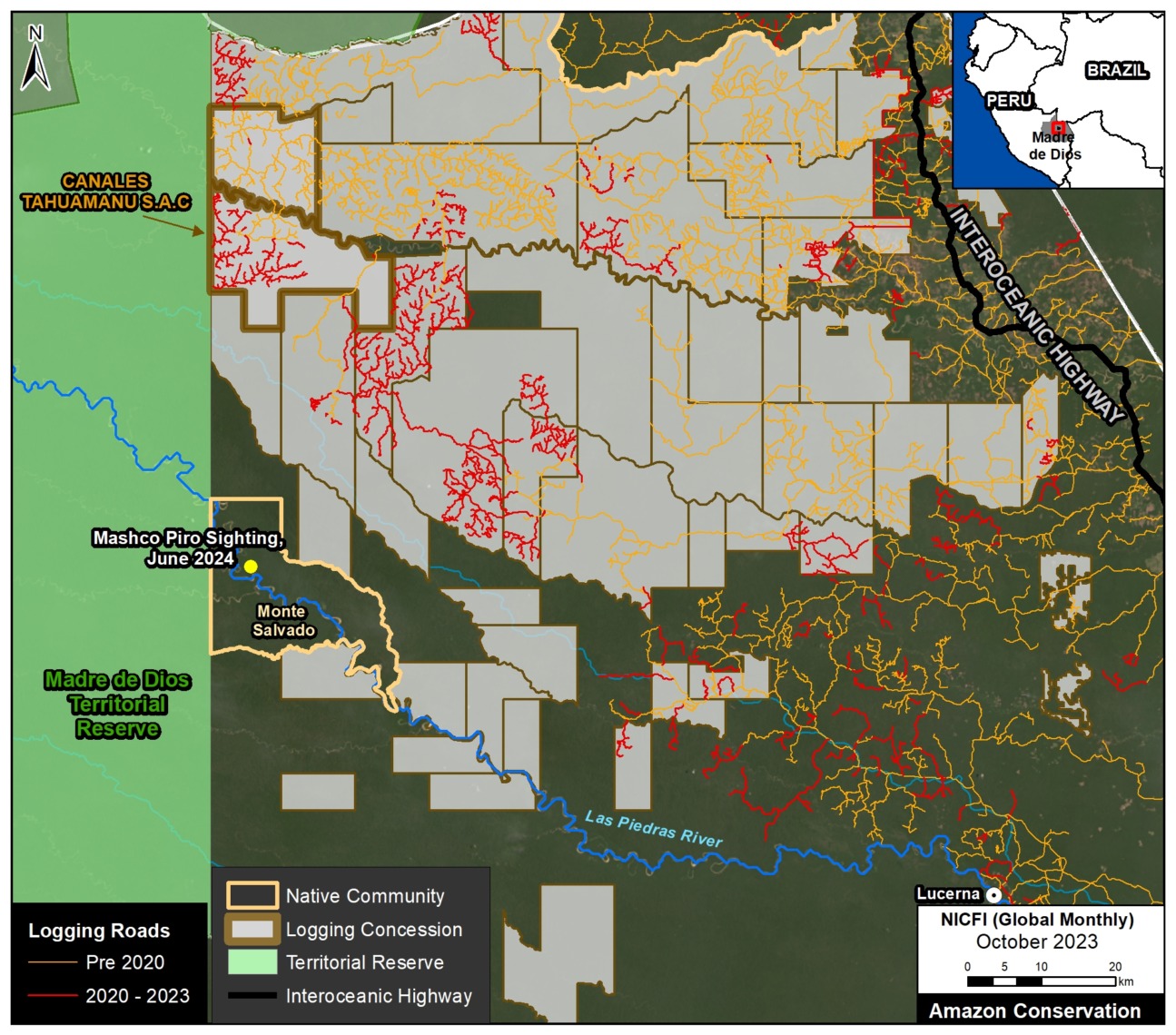

In late June 2024, a large group of Mashco Piro men appeared along the upper Las Piedras River, in the southern Peruvian Amazon (see photo), near the Yine Indigenous community of Monte Salvado.

The Mashco Piro are one of the largest and most emblematic uncontacted Indigenous groups in the world. They live in voluntary isolation in this remote but increasingly threatened area.

The photos and videos of this encounter, released by the organization Survival International, have generated worldwide news about the event.1

On the one hand, local experts and Indigenous representatives indicate that the Mashco Piro were likely searching the exposed riverbanks for turtle eggs, a usual occurrence that time of year when river levels are low.

On the other hand, the encounter also highlighted that the Mashco Piro are increasingly threatened by external pressures, especially by logging concessions granted by the Peruvian government.

In 2002, the Peruvian government created the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve to protect part of the Mashco Piro territory. However, some of their ancestral territory was left out and granted to logging companies.

Here, we analyze and illustrate the conflict caused by these logging concessions (and their logging roads) in the ancestral territory of the Mashco Piro.

Base Map of the Encounter Area

The Base Map shows the general area where the Mashco Piro recently appeared along the upper Las Piedras River (see “Encounter Area”) in relation to the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve, logging concessions, and logging roads.

Logging Concessions

As mentioned above, although the government created the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve to protect part of the Mashco Piro territory, their ancestral territory extended over areas now covered by logging concessions, causing the current context of risk and conflict. Much of the area east of the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve is subject to legalized logging in the ancestral territory.

Survival International’s press release made special note of the fact that some of the companies operating in Mashco Piro territory are additionally legitimized through certificates of sustainable origin and respect for human rights, in particular the concession operated by the company Canales Tahuamanu S.A.C.

Despite its controversial location next to the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve, this concession is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) as a responsible forestry operation that is environmentally appropriate and socially beneficial.

In contrast, the Indigenous Federation FENAMAD (Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and Tributaries) points out that this concession is within the proposed expansion zone of the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve, given its importance for the Mashco Piro and the high probability of conflict.

Logging Roads

We also highlight the recent expansion of logging roads,2 which is our best proxy for actual logging activity.

We indicate the most recent logging roads, built between 2020 and 2023, in red. Of these, we estimate the construction of over a thousand kilometers (1,013 km) in the logging concessions east of the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve.

Most notably, we detect the recent construction of 110 kilometers of new logging roads in the FSC-certified concession operated by Canales Tahuamanu, adjacent to the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve.

Notes

1 Examples of global coverage on the encounter include CNN, Reuters, and BBC. The original press release was produced by Survival International, and the photos and video they released can be viewed here.

2 Data for logging roads obtained from MOCAF (Monitoreo de Caminos Forestales), an initiative developed by the organization Conservación Amazónica to specifically track logging roads in Peru, within the SERVIR Amazonia Program.

Citation

Finer M, Ariñez A (2024) Uncontacted Indigenous group threatened by logging in the southern Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 216.

MAAP #191: Protecting Free-flowing & Intact River Corridors in the Ecuadorian Amazon

Here, we present a model conservation strategy, developed by the Ecuadorian Rivers Institute, that aims to protect river corridors that are both free-flowing and maintain riparian forest cover in the critical transition zone between the Andes mountains and the Amazon lowlands.

There are few remaining intact Andes-Amazon corridors, so this initiative is urgently needed in Ecuador and throughout the region.

The proposal targets strategic corridors that have three major characteristics:

1) Free-flowing, that is no major dams completely disrupting water flow from its source in the Andes down to the Amazon lowlands.

2) Intact riparian forest that extends at least 500 meters on each side of river.

3) No mining activity in the river or adjacent riparian zone.

This combination is estimated to be the minimum criteria needed to preserve the integrity of the biodiversity, aquatic ecosystems, and scenic landscapes of key river corridors in the tropical Andes.

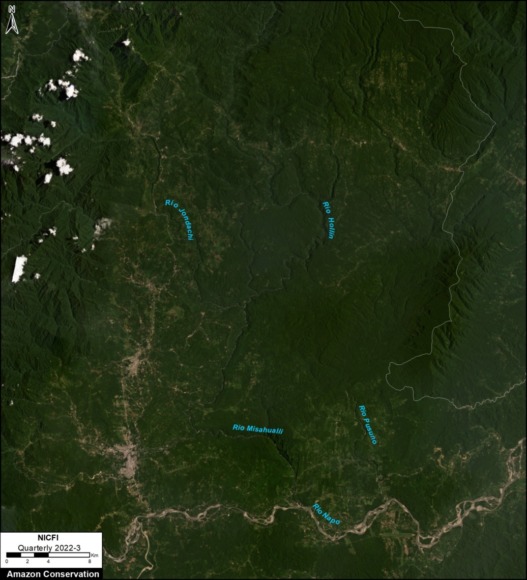

The Base Map illustrates the first two proposed corridors in Ecuador.

The first is the Jondachi-Hollín-Misahuallí-Napo Ecological Corridor. This multi-pronged corridor flows from the headwaters of the Jondachi and Hollin rivers (which originate in a series of protected areas, including Sumaco and Antisana National Parks), ultimately down to an intact stretch of the Napo River. This corridor totals 193 km of river and 18,675 hectares (46,145 acres) of riparian forest.

The second is the Piatua River Ecological Corridor, which channels water originating in Llanganates National Park. This corridor is shorter, totaling 46 km of river and 4,378 hectares (10,818 acres) of riparian forest.

Below is a recent satellite image of the Jondachi-Hollín-Misahuallí-Napo Ecological Corridor. Note the intact river and forest core to the east of the major road network, and north of the Napo River.

Social Component

This proposal would be accompanied by efforts to generate sustainable economic revenues for inhabitants of the region through low-impact tourism activities (such as kayaking, rafting, mountain biking, bird watching, and hiking) and financial incentives (such as land grants and carbon credits) to take pressure off of the increasing encroachment into riparian forests for wood harvesting and agricultural expansion.

There would also be programs to promote intensive reforestation in the degraded areas outside of the corridor as a way of creating employment opportunities for the local communities.

Below is an aerial photo of a section of the corridor, highlighting some of the key components of the proposal: free-flowing river, intact riparian corridor, and sustainable, low-impact tourism.

Citation

Terry M, Finer M, Ariñez A (2023) Protecting Free-flowing & Intact River Corridors in the Ecuadorian Amazon. MAAP: 191.