This is the third in a series of reports documenting the expansion of gold mining in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

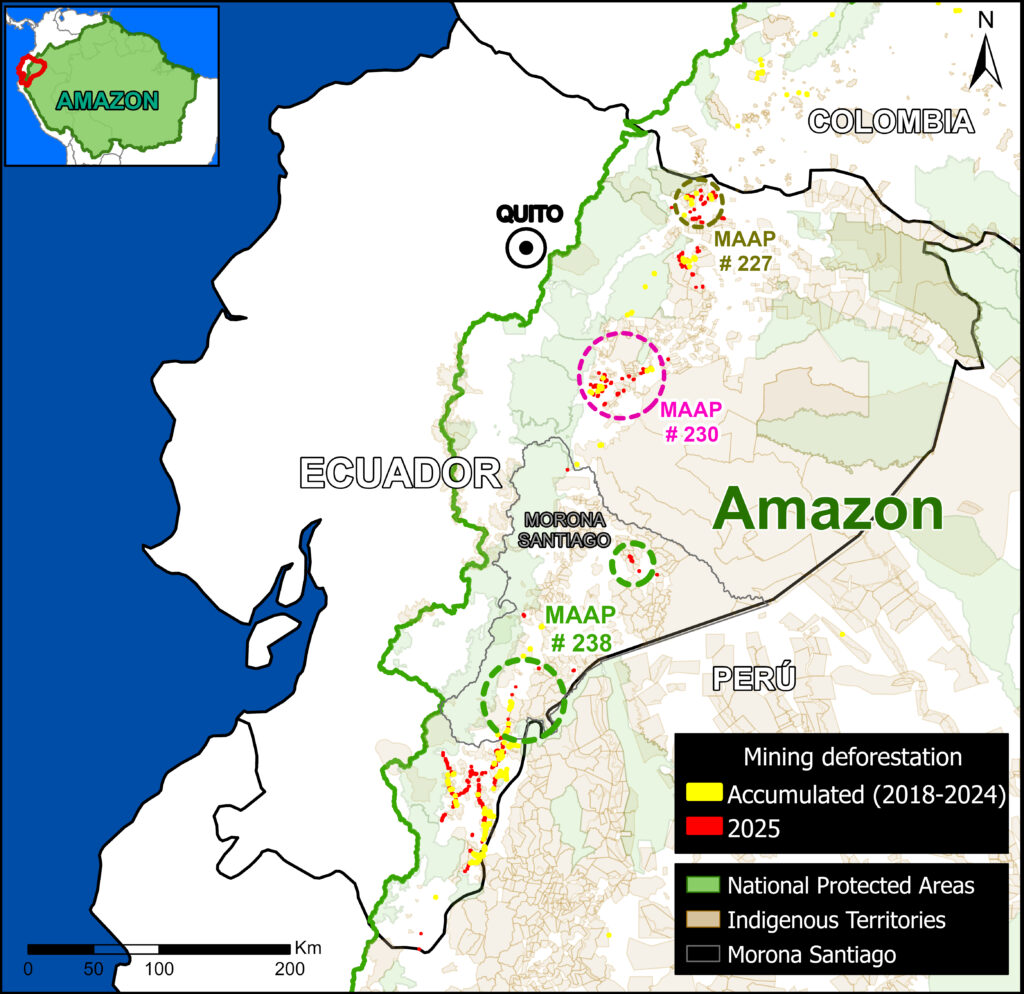

Previous reports (MAAP #227 and MAAP #230) analyzed the progress of this activity in the northern and central parts of the country, respectively, with a focus on the provinces of Sucumbíos and Napo.

This new report focuses on mining deforestation in the southern Ecuadorian Amazon, in the province of Morona Santiago.

Since 2023, Amazon Conservation, in collaboration with Earth Genome and the Pulitzer Center, has been developing an online geoviewer known as Amazon Mining Watch (MAAP #226). This virtual tool automates the analysis of satellite imagery using machine learning to identify areas affected by mining throughout the Amazon since 2018, and now features quarterly updates for the systematic detection of new gold mining fronts in real time.

Base Map 1 shows the locations of recent confirmed mining-related deforestation using detections from the latest quarterly update of Amazon Mining Watch across the Ecuadorian Amazon, in relation to the cumulative mining impact area (2018-2024). It can be seen that several Indigenous territories converge in the analysis area (purple circles).

Morona Santiago, the second largest province in Ecuador, is one of the country’s main conservation areas and the ancestral home of the Shuar and Achuar Indigenous nationalities. However, it is currently facing a growing threat due to the expansion of gold mining.

Case Studies

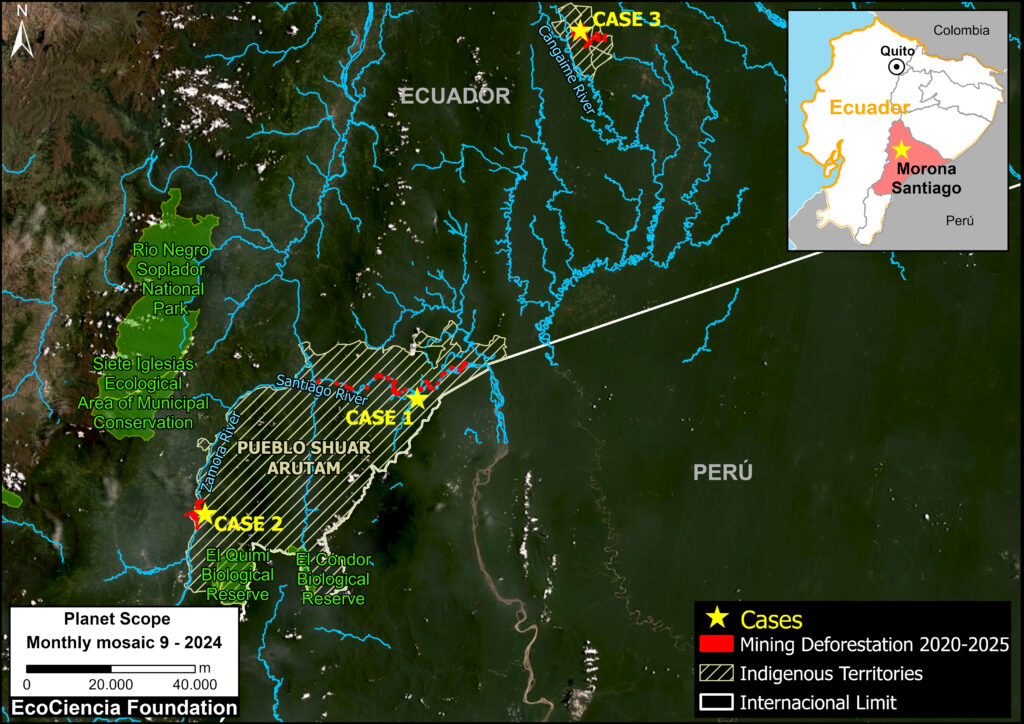

Cases 1 and 2 focus on mining activities within Shuar Arutam territory (Note 1), in southern Morona Santiago (see Base Map 2).

This territory faces increasing pressure from the expansion of the agricultural frontier, selective logging, and especially mining.

Over half (55%) of the territory is under concession for the extraction of metals such as gold, silver, and copper.

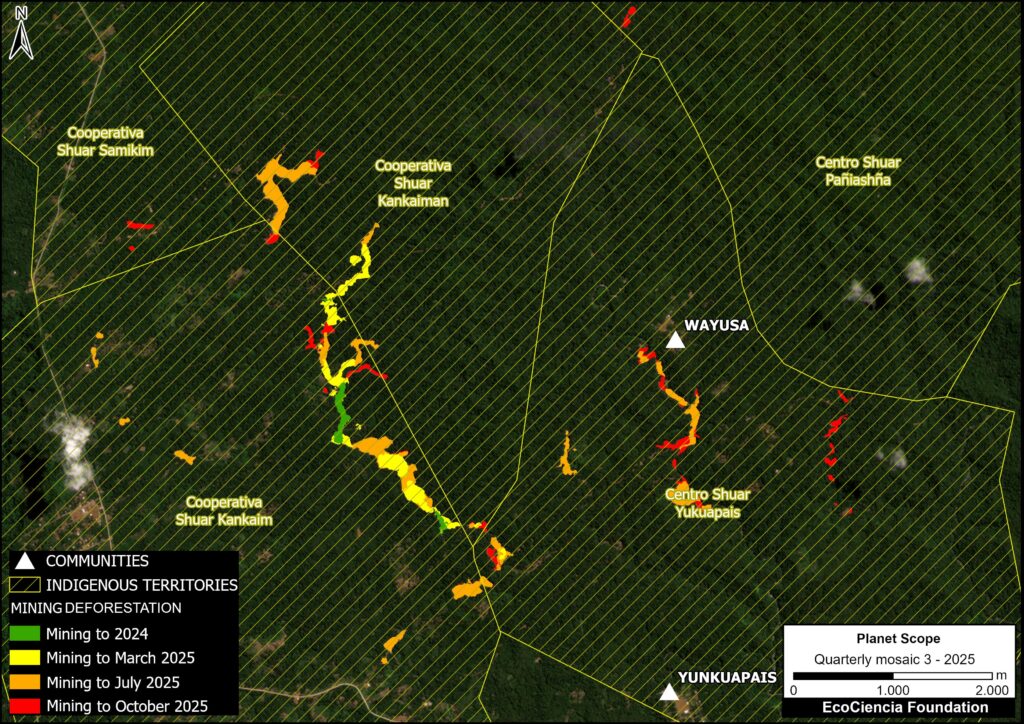

Case 3 focuses on mining in the north of the province; here, illicit mining has been identified within several Shuar territories (Samikim, Kankaiman, KainKaim, Yukuapais, and Pañiashña).

We conducted satellite monitoring aimed at quantifying the impact of illegal gold mining in these three case studies during the period 2020-2025.

Mining Activity in Morona Santiago (2020-2024)

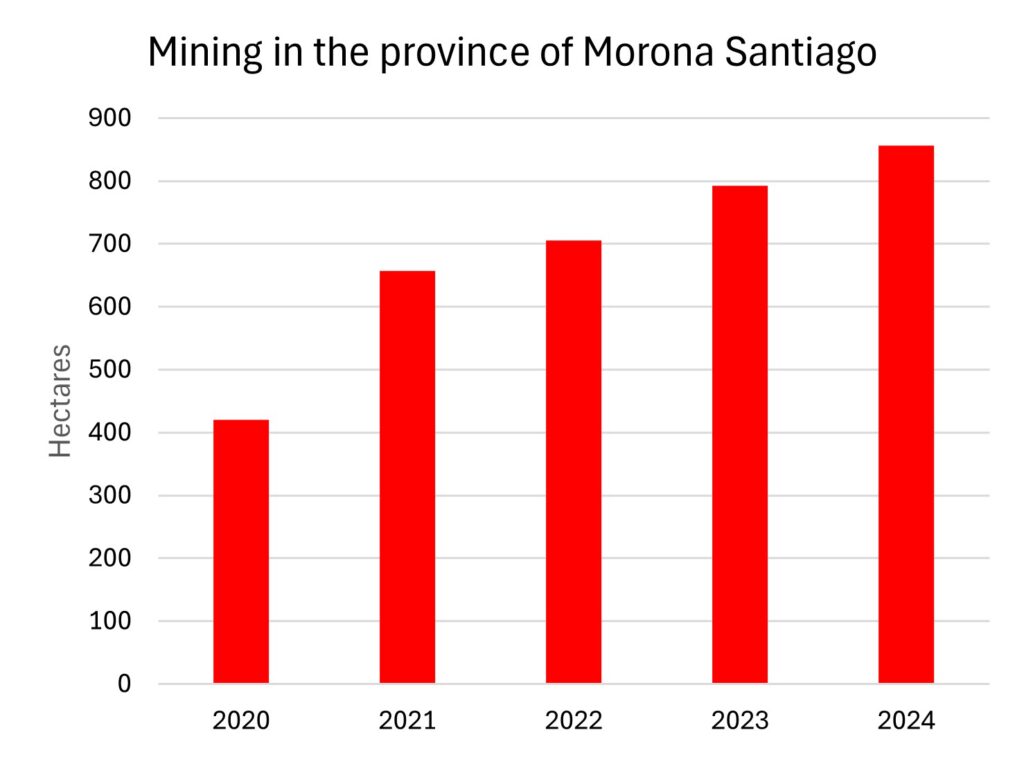

Graph 1 shows the cumulative mining deforestation in the Morona Santiago province between 2020 and 2024.

In 2020, mining impacted around 420 hectares as our baseline. In the subsequent years, we documented a rapid increase, reaching a total of 856 hectares (2,115 acres) by 2024.

This represents a doubling of the affected area in just four years.

Case 1. Santiago River

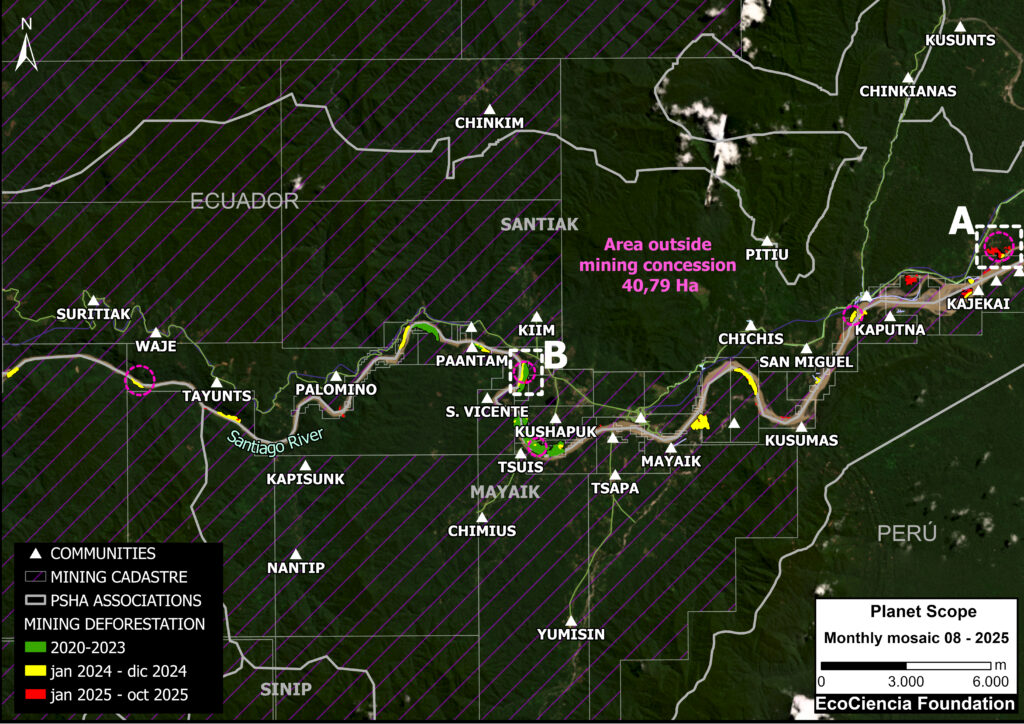

This case is located along the Santiago River (see Case 1 in Base Map 2), between the Shuar Santiak, Mayaik, and Nunkui associations in the territory of the Shuar Arutam (see Note 2)

This river is among the most threatened areas in the territory, especially due to the expansion of mining.

In this area, we detected the mining deforestation of 197 hectares (486 acres) between January 2020 and October 2025.

Of this total, we estimate that 20% (41 hectares; 101 acres) is likely illegal, occurring outside areas authorized for mining activity

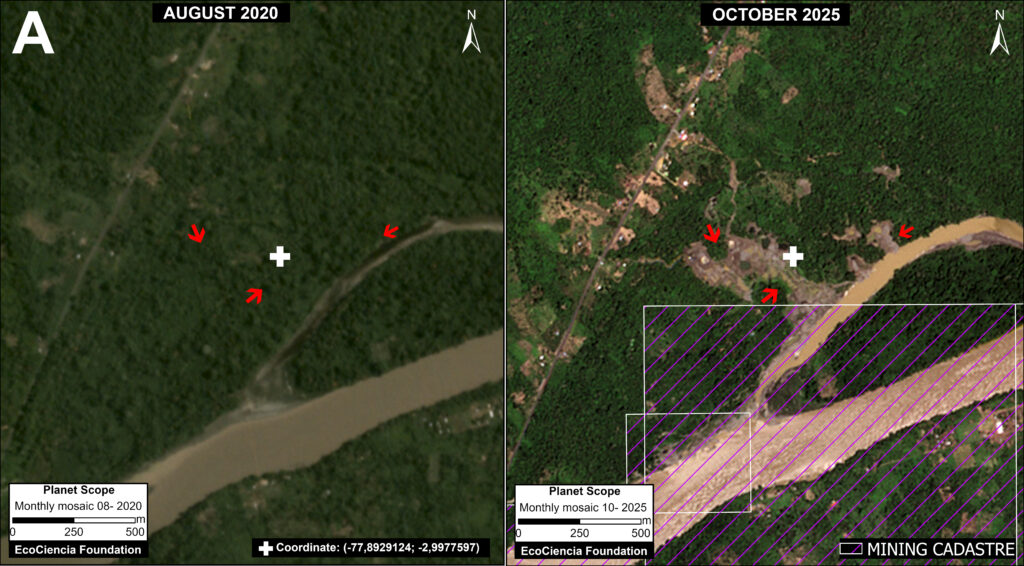

We selected two focal areas, both with recent mining impacts, along the Santiago River (see Areas A and B in Case 1).

Panel 1 illustrates the situation in Area A, comparing mining deforestation (as well as the expansion of access roads and the impact on the river) between August 2020 (left panel) and October 2025 (right panel). Of this total forest loss, we confirmed that 12 hectares (30 acres) were located outside of authorized concessions and therefore likely illegal.

In the Annex, Panel 2 shows an example of the territorial monitoring carried out by the Shuar Arutam using drones.

Panel 3 illustrates the situation in Area B, comparing mining deforestation (and impact to the river) between August 2020 (left panel) and September 2025 (right panel). Of this total forest loss, we confirmed that 9 hectares (22 acres) were located outside of authorized concessions and therefore likely illegal.

In the Annex, Panel 4 shows an example of the territorial monitoring carried out by the Shuar Arutam using drones.

Case 2. Nayap

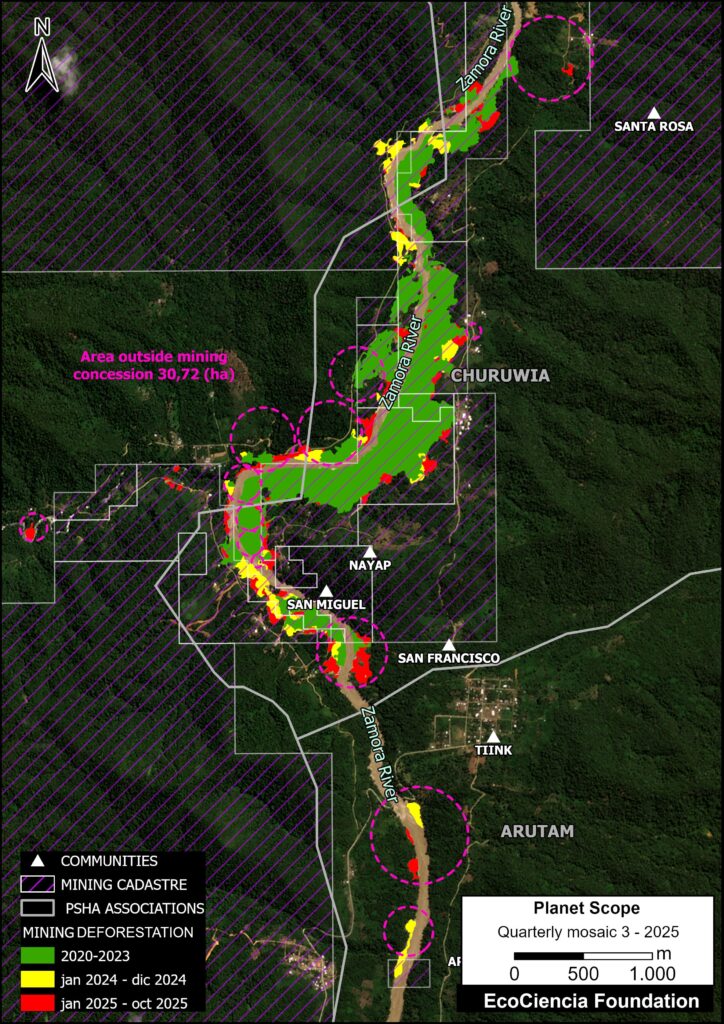

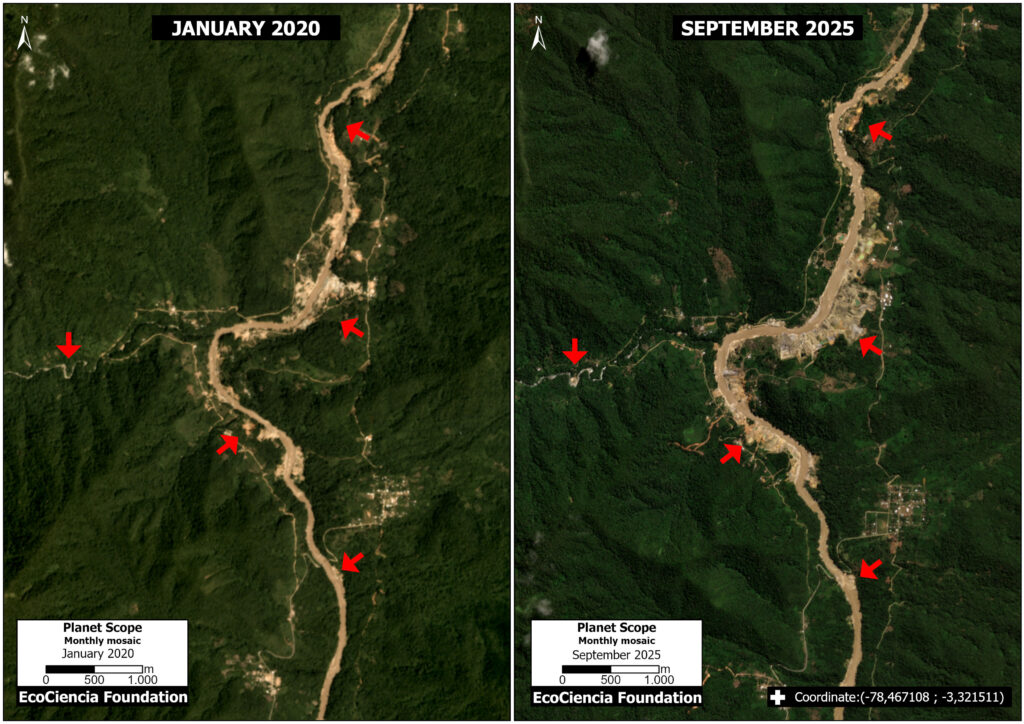

This case is located along the Zamora River (see Case 2 in Base Map 2), on the western edge of the Churuwia association, near the Shuar Arutam community of Nayap. This territory is traditionally inhabited by Shuar communities.

In this area, we detected the mining deforestation of 164 hectares (405 acres) between January 2020 and October 2025.

Of this total, we estimate that 20% (31 hectares; 76 acres) is likely illegal, occurring outside areas authorized for mining activity

Panel 5 illustrates the situation in Case 2, comparing mining deforestation (and impact to the river) between January 2020 (left panel) and September 2025 (right panel).

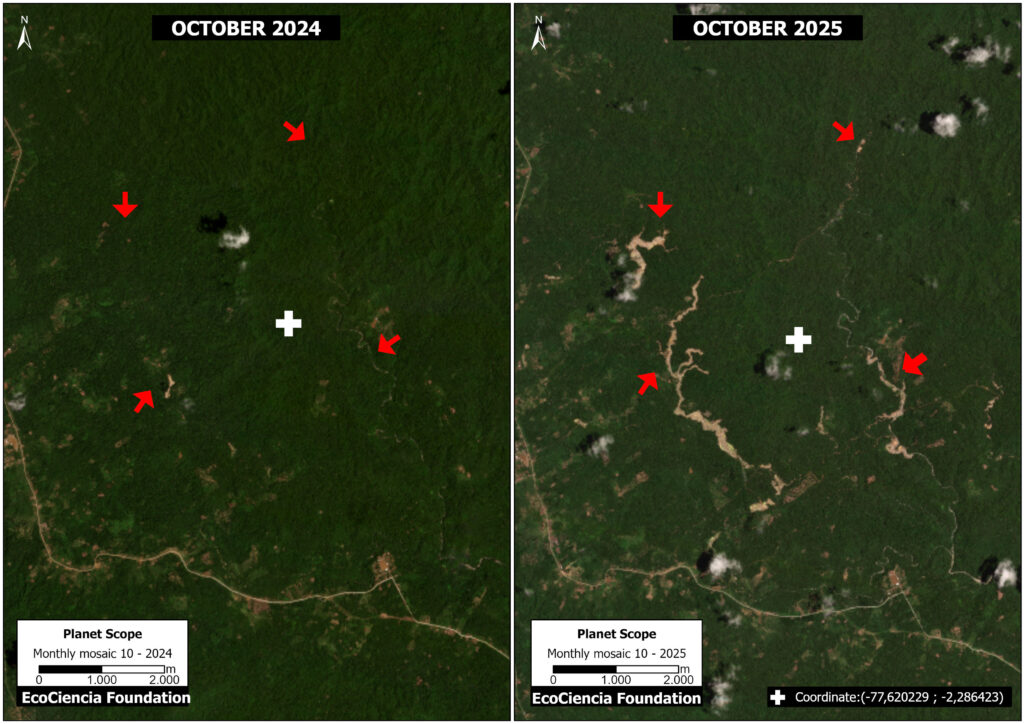

Case 3. Taisha

This case is located in the northern part of Morona Santiago (see Case 3 in Base Map 2), within the Shuar Indigenous territories of Samikim, Kankaiman, Kainkaim, Yukuapais, and Pañiashña.

In this area, we detected the mining deforestation of 100 hectares (247 acres) between October 2024 and October 2025 (see Case 3).

Panel 6 illustrates the situation in Case 3, comparing mining deforestation (and road expansion) between October 2024 (left panel) and October 2025 (right panel). The opening of these roads facilitates direct access for machinery, personnel, and supplies to previously inaccessible areas, increasing connectivity and accelerating the occupation of the territory.

Policy recommendations

1. Strengthening Indigenous governance

The cases analyzed show that, while Ecuadorian law broadly recognizes the right to citizen participation and the collective rights of indigenous peoples and nationalities in environmental and mining decisions, its implementation faces significant challenges. The legal framework distinguishes between environmental consultation as a diffuse right and prior, free, and informed consultation as a collective right, regulated by the Mining Law, the Organic Environmental Code, the Organic Law on Citizen Participation, and recent secondary legislation. However, the historical absence of a specific law and the gaps in the practical application of these mechanisms have generated tensions and questions regarding the quality of intercultural dialogue, effective access to information, and the real influence of communities in decision-making.

While the Escazú Agreement strengthens the Ecuadorian state’s obligations regarding environmental participation, access to information, and environmental justice, the cases reviewed show that these standards do not always translate into substantive processes that strengthen indigenous territorial governance. In particular, prior consultation is often conducted in isolation from permanent community-based monitoring and oversight mechanisms, which limits communities’ ability to continuously monitor extractive activities affecting their territories.

In this context, to strengthen indigenous governance, it is recommended to formally recognize indigenous monitors as legitimate actors within environmental monitoring and control processes, coordinating their work with existing institutional mechanisms. Additionally, it is proposed to implement a permanent satellite monitoring system integrated with community observation systems, allowing for the early detection of road construction and other illegal activities, and contributing to the realization of the principles of effective participation and intercultural dialogue.

2. Biocultural territorial planning

The Constitution of Ecuador recognises interculturalism and plurinationality (articles 1 and 250), as well as the legal systems of indigenous peoples; similarly, the Escazú Agreement (article 7) promotes inclusive participation with intercultural approaches.

Within this framework, it is recommended to adopt a biocultural territorial planning approach that integrates indigenous life plans and governance systems as binding instruments in public decision-making.

No mining project can be approved without first being integrated into these local instruments, which are developed through community assemblies.

3. Controlling road expansion in Indigenous territories

The development of a road in the Ecuadorian Amazon involves a series of fundamental environmental requirements, established in the national regulations in force as of 2025, to guarantee the protection of the environment, biodiversity, and the rights of local and indigenous communities.

These requirements are regulated primarily by the Organic Environmental Code (COA) and its Regulations (issued through Executive Decree 752 and subsequent amendments), the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court of Ecuador regarding environmental rights and the rights of Nature; and international human rights treaties such as the Escazú Agreement (in force in Ecuador since 2021).

We recommend requiring a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for all road projects in areas of high ecological sensitivity, especially in indigenous territories and protected areas.

The construction of roads without an environmental impact assessment and without applying the precautionary principle should be considered illegal and subject to reversal, prioritizing ecological restoration processes with the participation of local communities.

Notes

(1) Located in the Cordillera del Cóndor, between the Zamora and Yaupi rivers, the Shuar Arutam community is part of the Abiseo–Cóndor–Kutukú bio-corridor, an ecological bridge that connects the Tropical Andes biodiversity hotspot with one of the largest continuous wilderness areas of the Amazon rainforest. This mountain range protects areas of high biological importance, safeguards water sources, and harbors habitats of endemic species. Furthermore, it constitutes the ancestral territory of the Shuar people, where sacred sites preserve their spiritual and collective memory.

(2) The Santiago River flows through the Abiseo–Cóndor–Kutukú bio-corridor, one of the main biodiversity hotspots in the Ecuadorian Amazon (CARE et al., 2012), characterized by highly diverse ecosystems and the presence of numerous terrestrial and aquatic species (Schulenberg & Awbrey, 1997). Recent research even suggests that the river’s unique environmental conditions may be promoting speciation processes in fish due to its natural isolation (Provenzano & Barriga, 2018). In addition to mining, threats include hydroelectric projects, deforestation, overfishing, and the introduction of invasive species, which generate increasing pressures that degrade its ecosystems and severely affect native species.

Annex

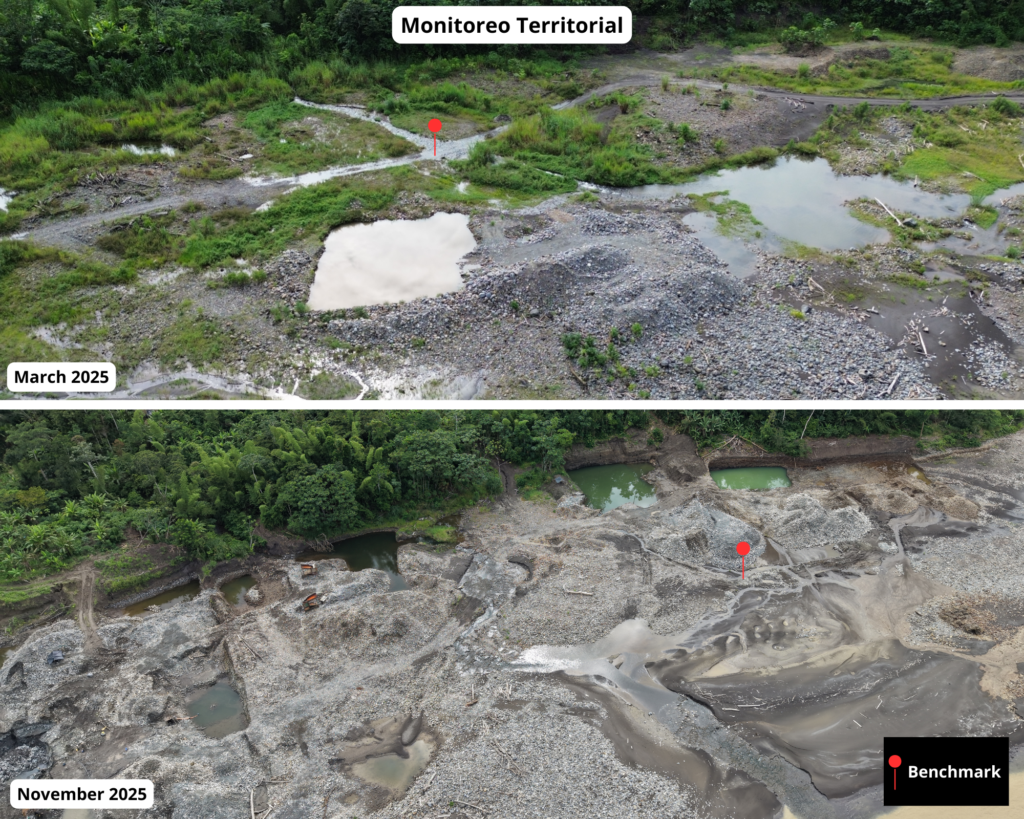

Panels 2 and 4 highlight the territorial monitoring carried out by the Shuar Arutam using drones.

Panel 2 shows the expansion of mining deforestation between May (top panel) and November (bottom panel) of 2025.

Panel 4 shows the expansion of mining impact between March (top panel) and November (bottom panel) of 2025, including more extensive excavation fronts and a greater accumulation of sediment.

Citation

Villa J, García C, Barriga J, Finer M, Josse C, Aguilar C (2025). Minería en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana Sector Sur – Provincia de Morona Santiago. MAAP: 238.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Shuar Arutam for their contributions to this report.

This report is part of a series focused on the Ecuadorian Amazon through a strategic collaboration between the organizations EcoCiencia Foundation and Amazon Conservation, with the support of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.