The company Planet is pioneering the use of high-resolution “small satellites” (Image 59a). They are a fraction of the size and cost of traditional satellites, making it possible to produce and launch many as a large fleet. Indeed, Planet now operates 149 small satellites, known as Doves, the largest fleet in history. The Doves capture color imagery at 3-5 meter resolution, and will line up (like a string of pearls) to cover everywhere on Earth’s land area every day.

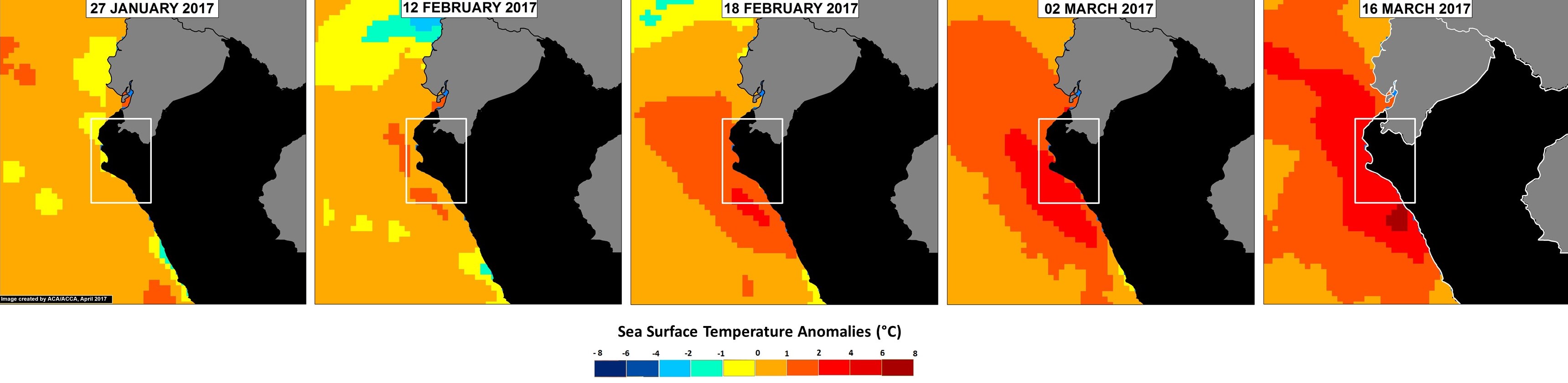

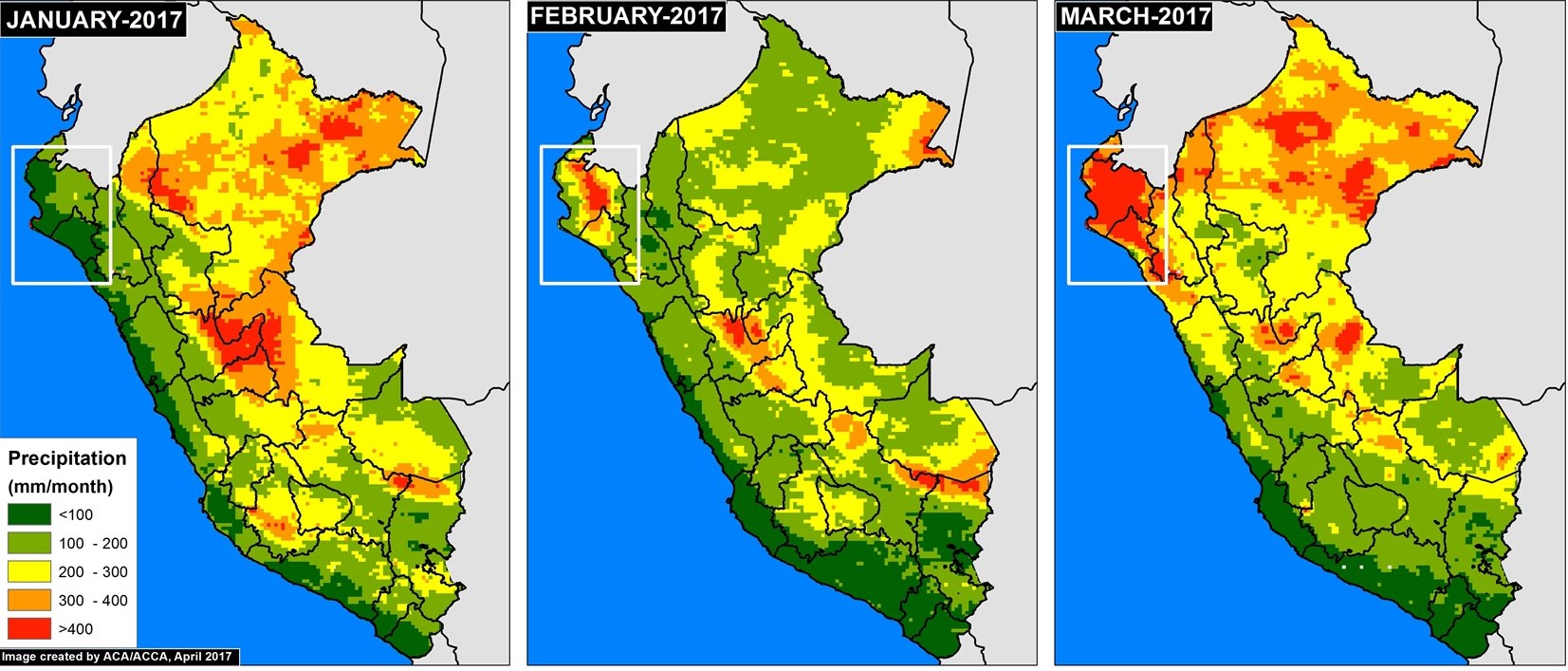

Over the past year, MAAP* has demonstrated the power of Planet imagery to monitor deforestation and degradation in near real-time in the Amazon. A consistent flow of new, high-resolution imagery is needed for this type of work, making Planet’s fleet model ideal. Below, we provide a recap of key MAAP findings based on Planet imagery, for a diverse set of cases including gold mining, agriculture deforestation, logging roads, wildfire, blowdowns, landslides, and floods.**

*MAAP has been fortunate to have access to Planet imagery via the Ambassador program.

**Note: In the images below, the red dot (•) indicates the same location across time between panels.

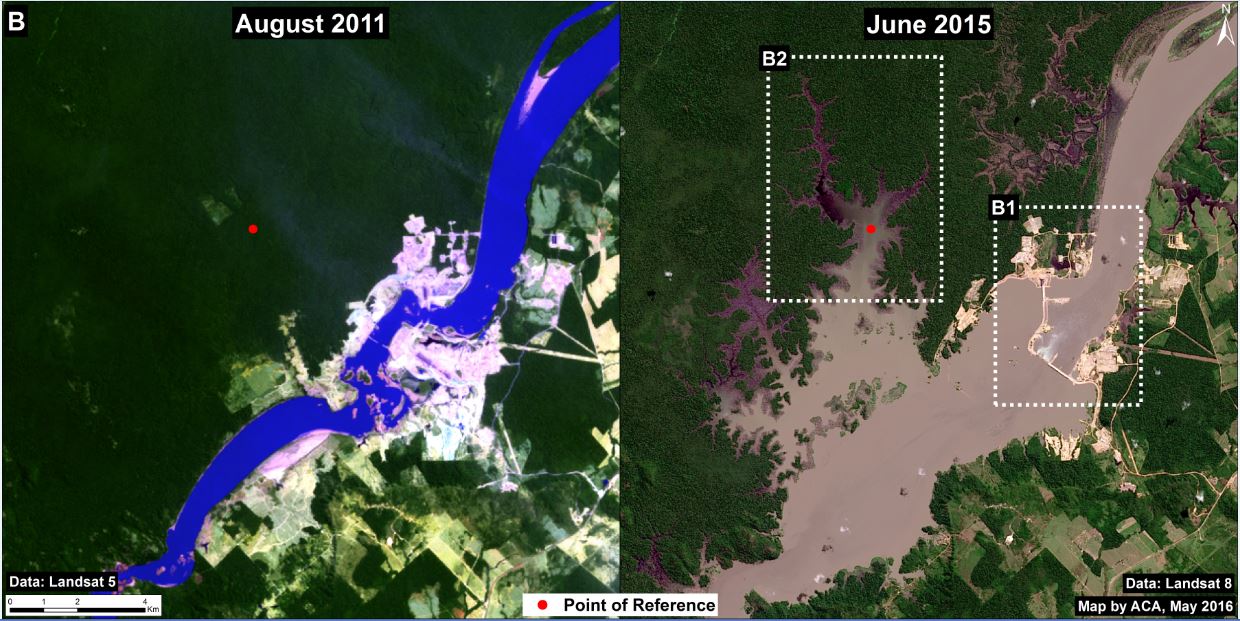

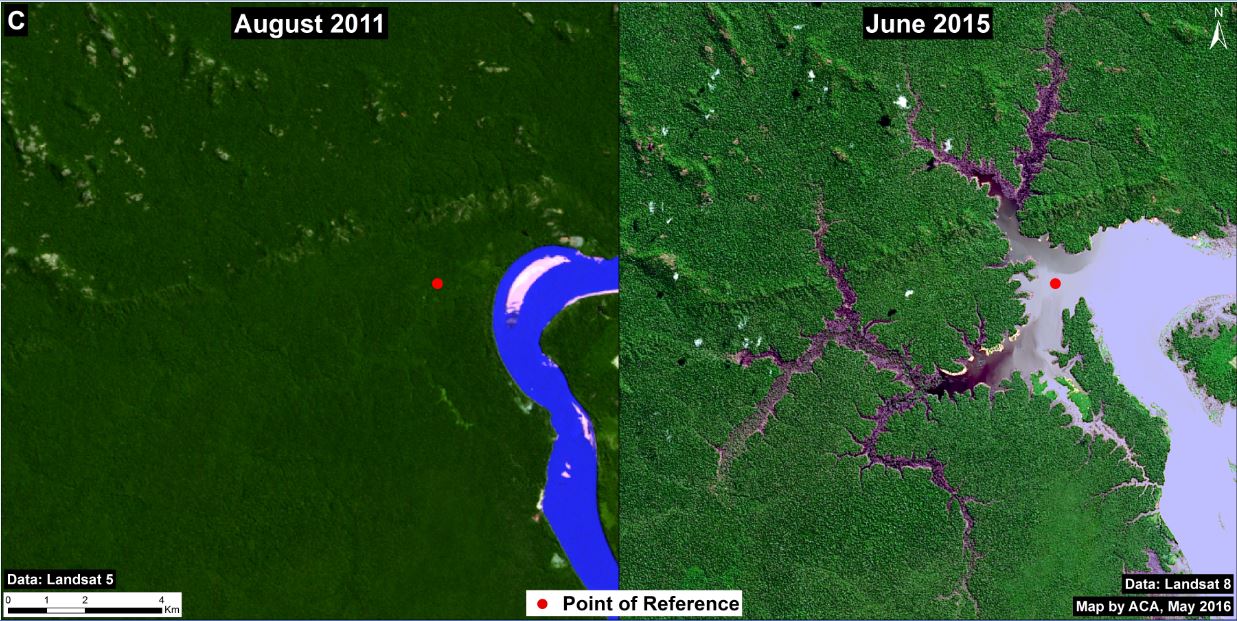

Illegal Gold Mining

We used Planet imagery to closely track the recent illegal gold mining invasion of Tambopata National Reserve, a mega-diverse protected area in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Image 59b is a GIF showing the full invasion: from the initial invasion in January 2016, to subsequent deforestation advances in July and November 2016, and the most recent image in March 2017. The total deforestation from the invasion is over 1,235 acres. These images were an important resource for authorities, civil society, and the media responding to the situation.

Illegal Agriculture Deforestation

We used Planet imagery to document numerous cases of small-scale deforestation for illegal agricultural practices. These examples are important because, cumulatively, small-scale deforestation represents the vast majority (80%) of forest loss events in the Peruvian Amazon (see MAAP Synthesis #2). Image 59c shows the rapid appearance of several new agricultural plots between May (left panel) and June (right panel) 2016 within an important natural protected area in the central Peruvian Amazon, El Sira Communal Reserve.

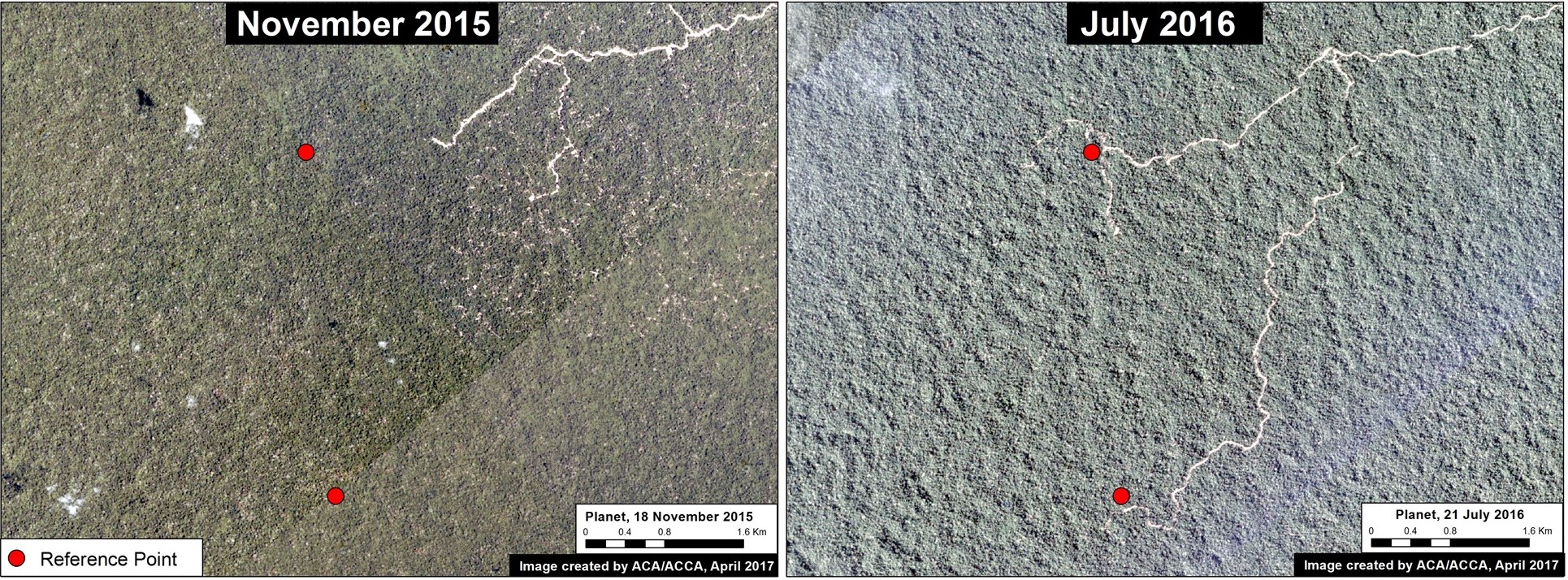

Logging Roads

We used Planet imagery to show the rapid construction of logging roads. For example, Image 59d shows the construction of a logging road in the buffer zone of an important national park in the central Peruvian Amazon (Cordillera Azul) between November 2015 (left panel) and July 2016 (right panel).

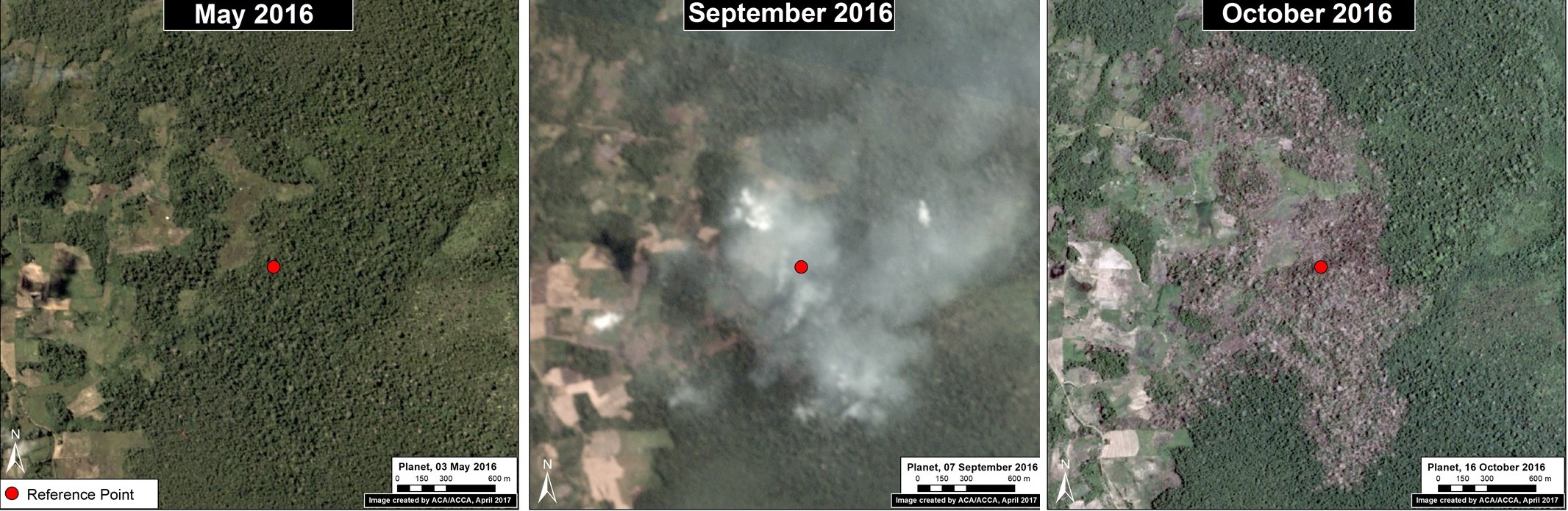

Wildfire

Planet imagery was also an important resource to monitor the intense wildfires in Peru last year. Image 59e shows forest loss from an escaped agricultural fire in the northern Peruvian Amazon between May (left panel) and October (right panel) 2016. Note the imagery even caught the smoke from the fires in September (middle panel).

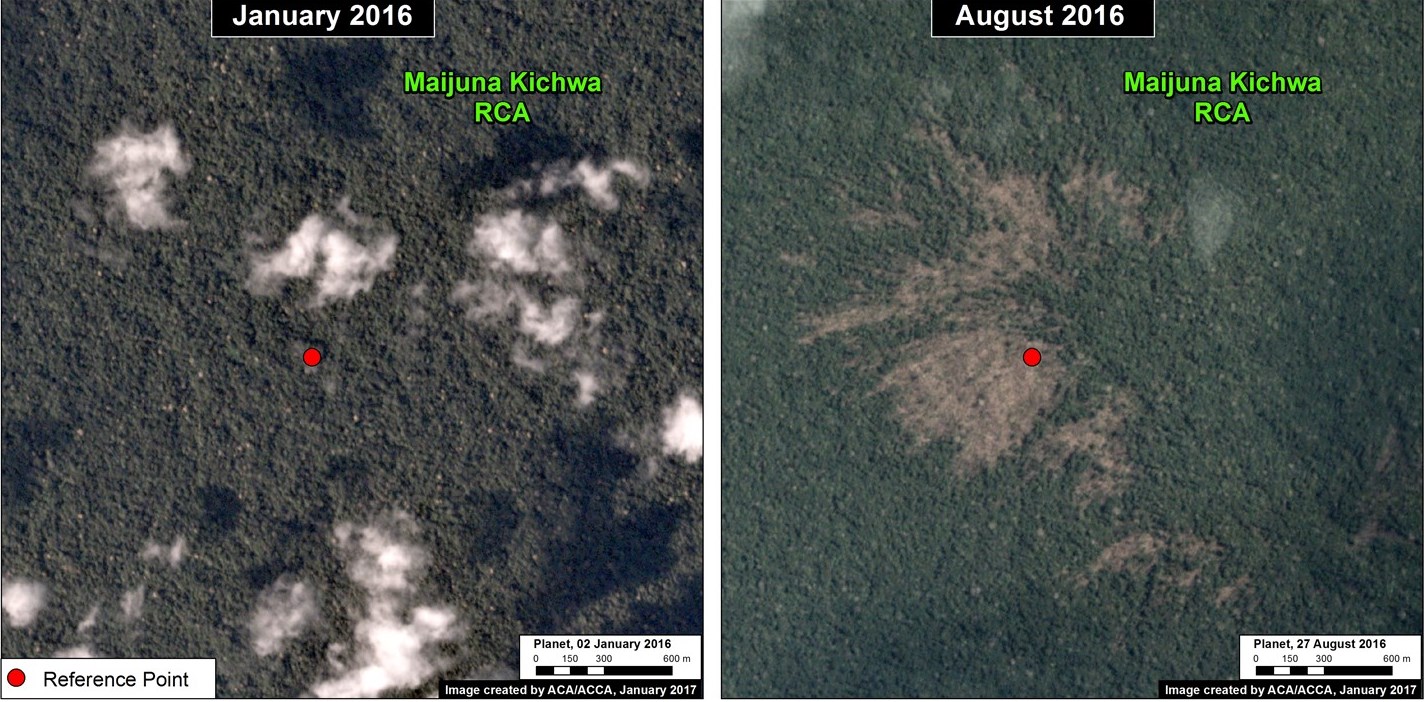

Blowdowns

We used Planet to help document a little-known, but important, type of natural forest loss in the Peruvian Amazon: blowdown due to strong winds from localized storms known as “hurricane winds.” Image 59f shows a high-resolution view of a recent major blowdown event between January (left panel) and August (right panel) 2016 in the northern Peruvian Amazon.

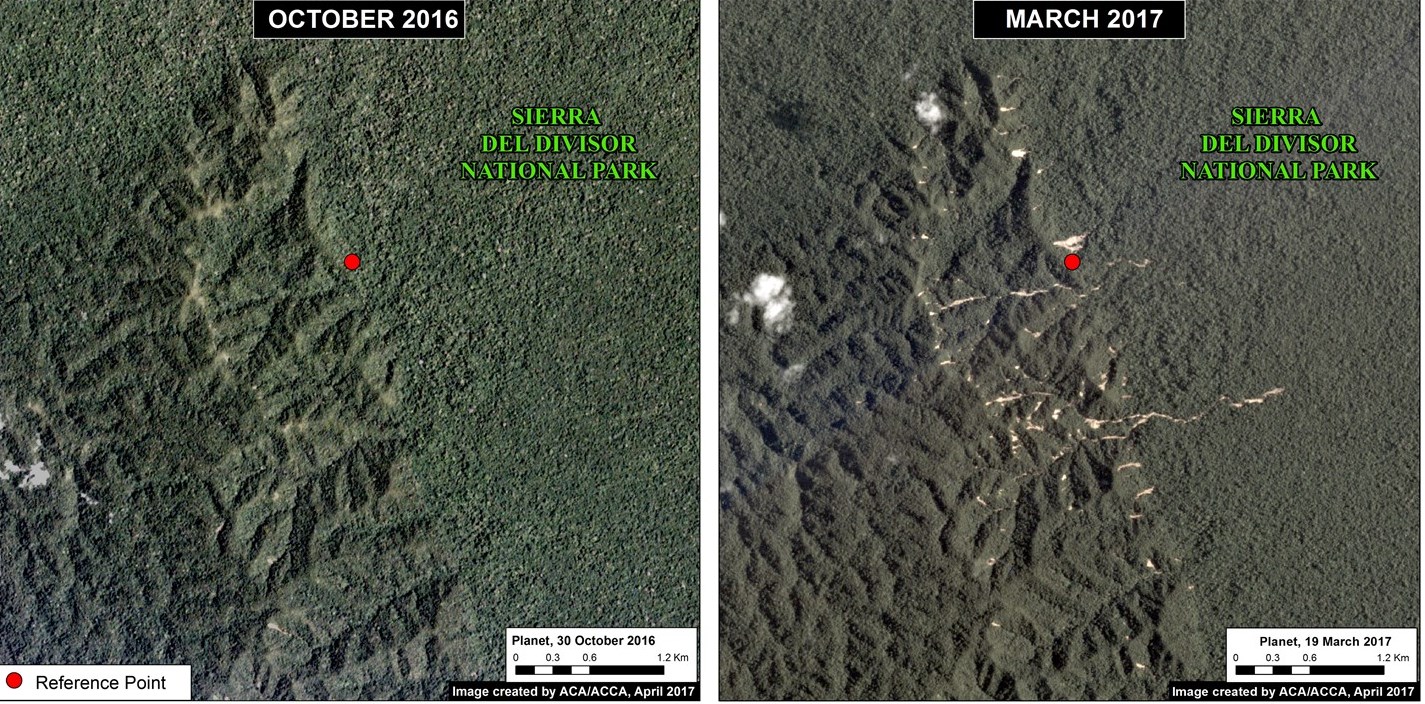

Landslides

Planet imagery recently revealed an interesting natural phenomenon: a major landslide within a remote, rugged section of Peru’s newest national park, Sierra del Divisor. Image 59g shows the area between October 2016 (left panel) and March 2017 (right panel).

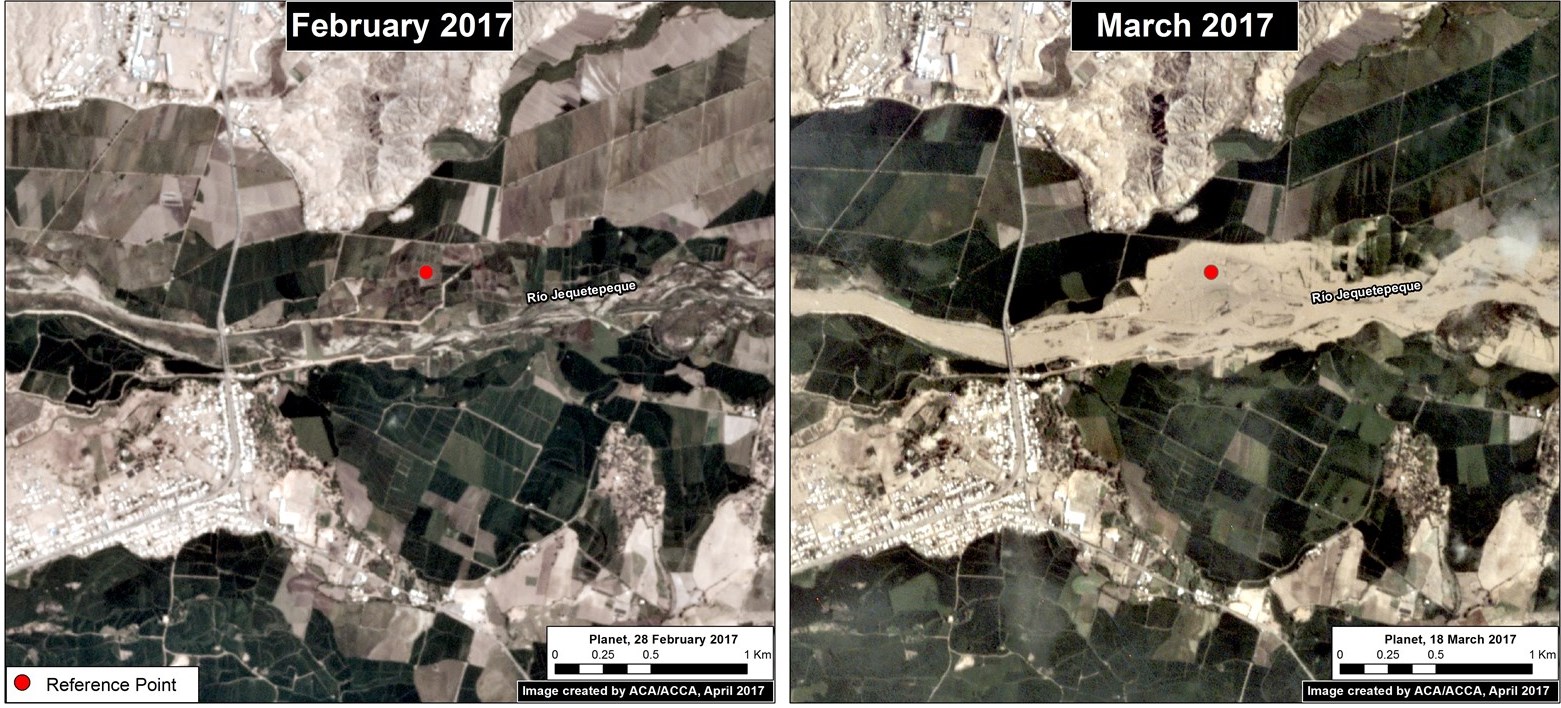

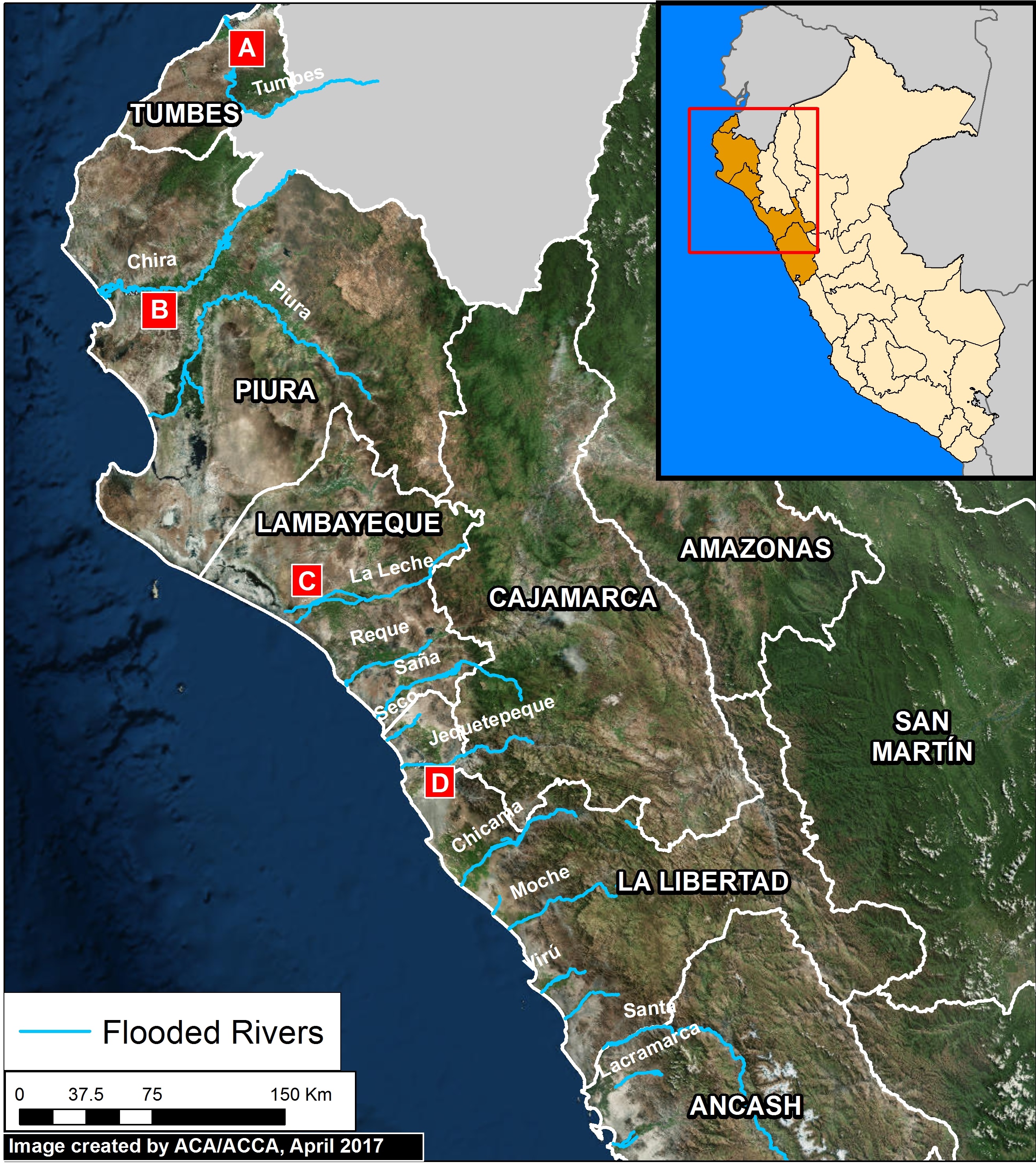

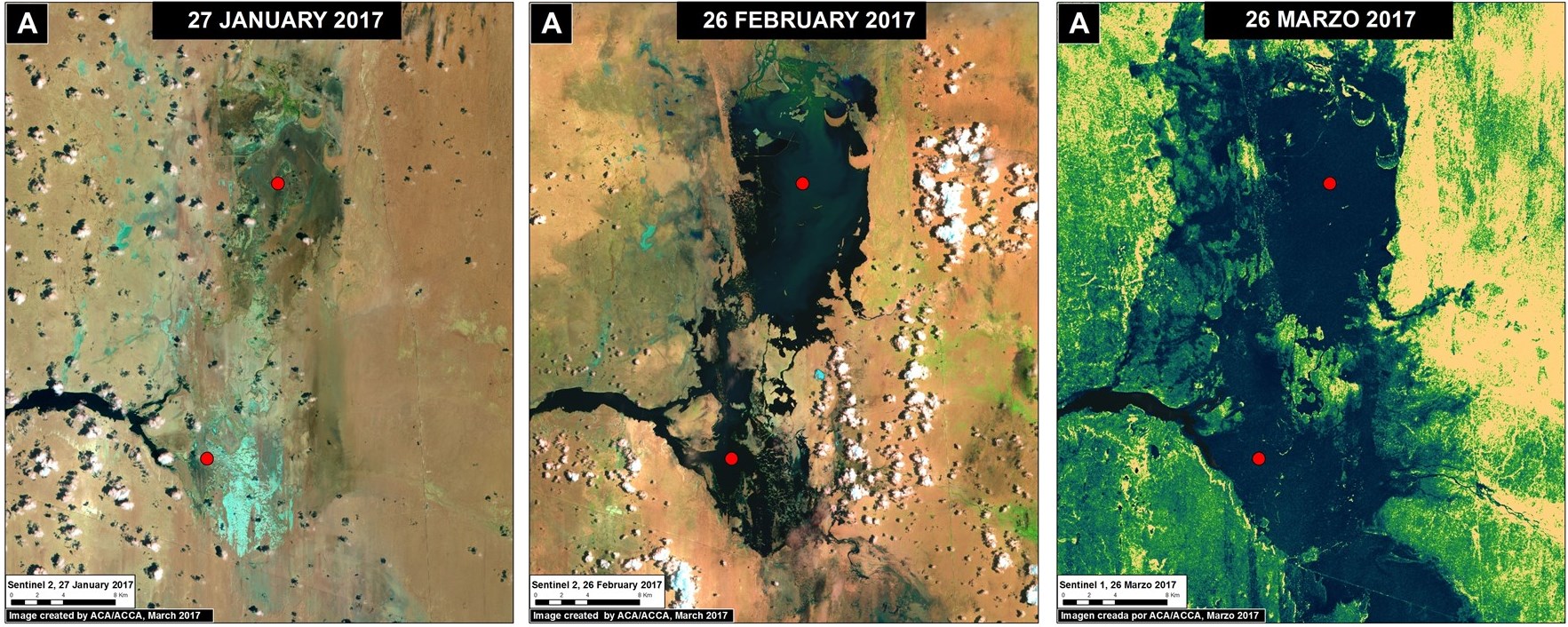

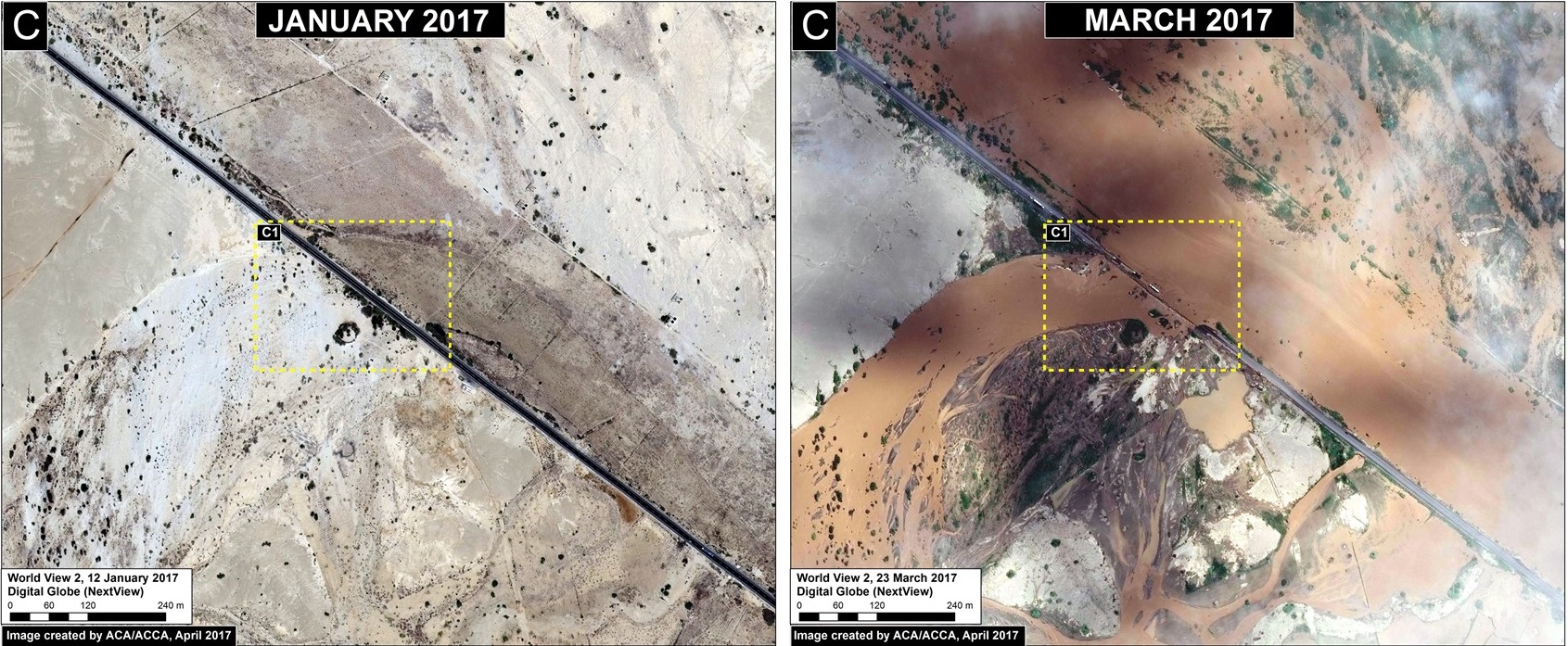

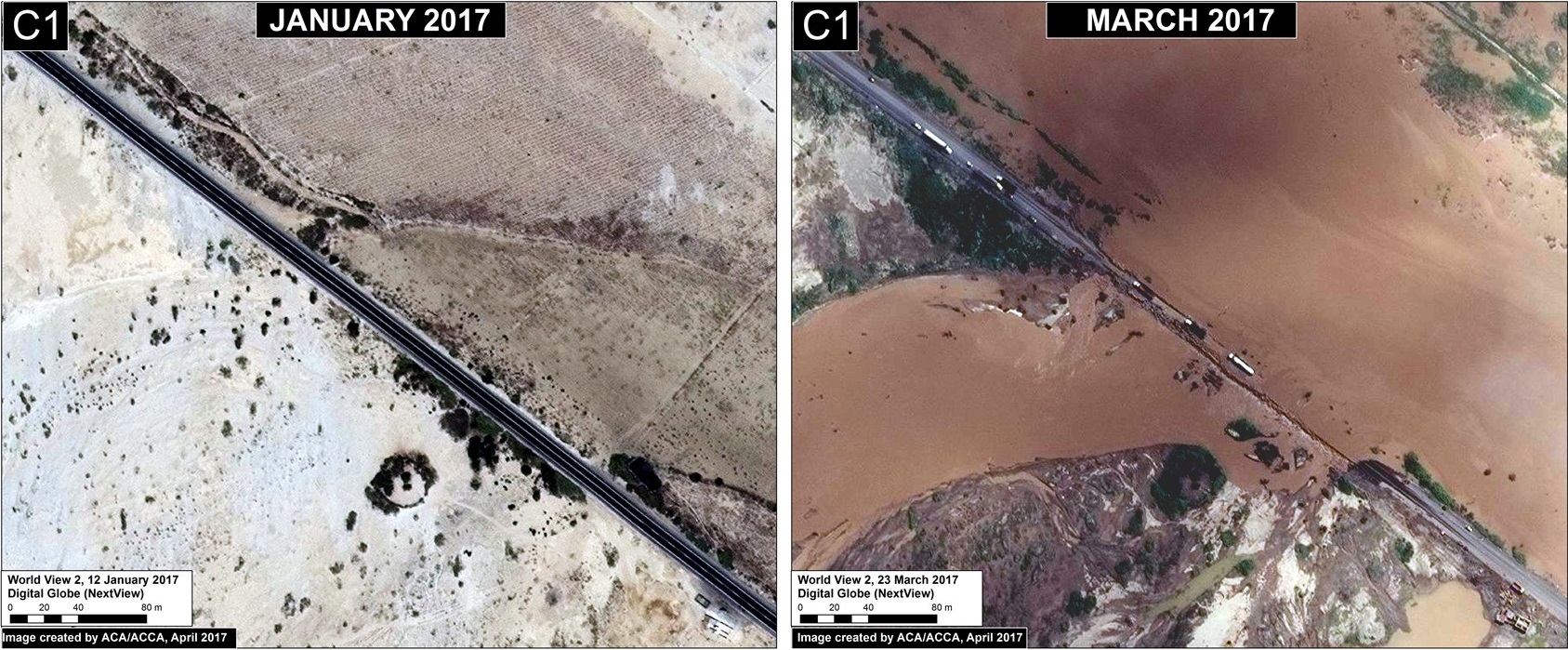

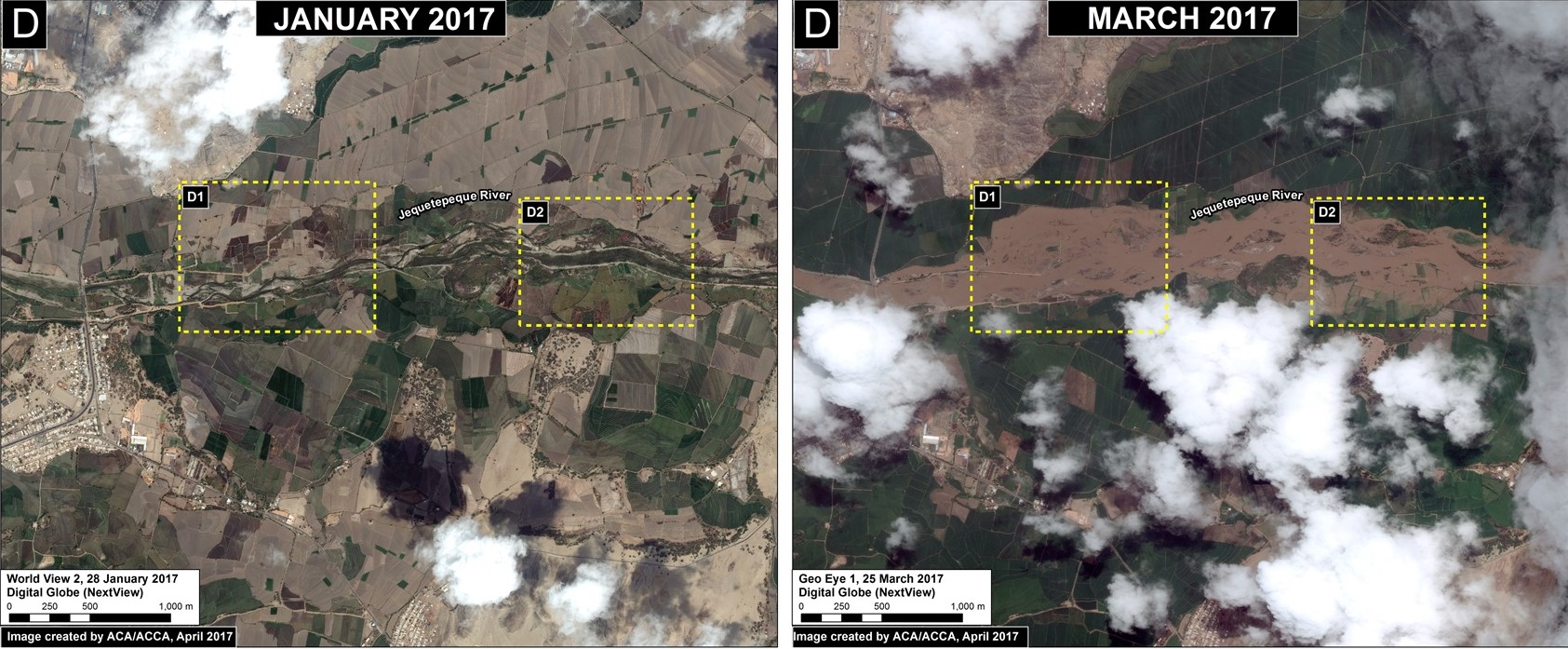

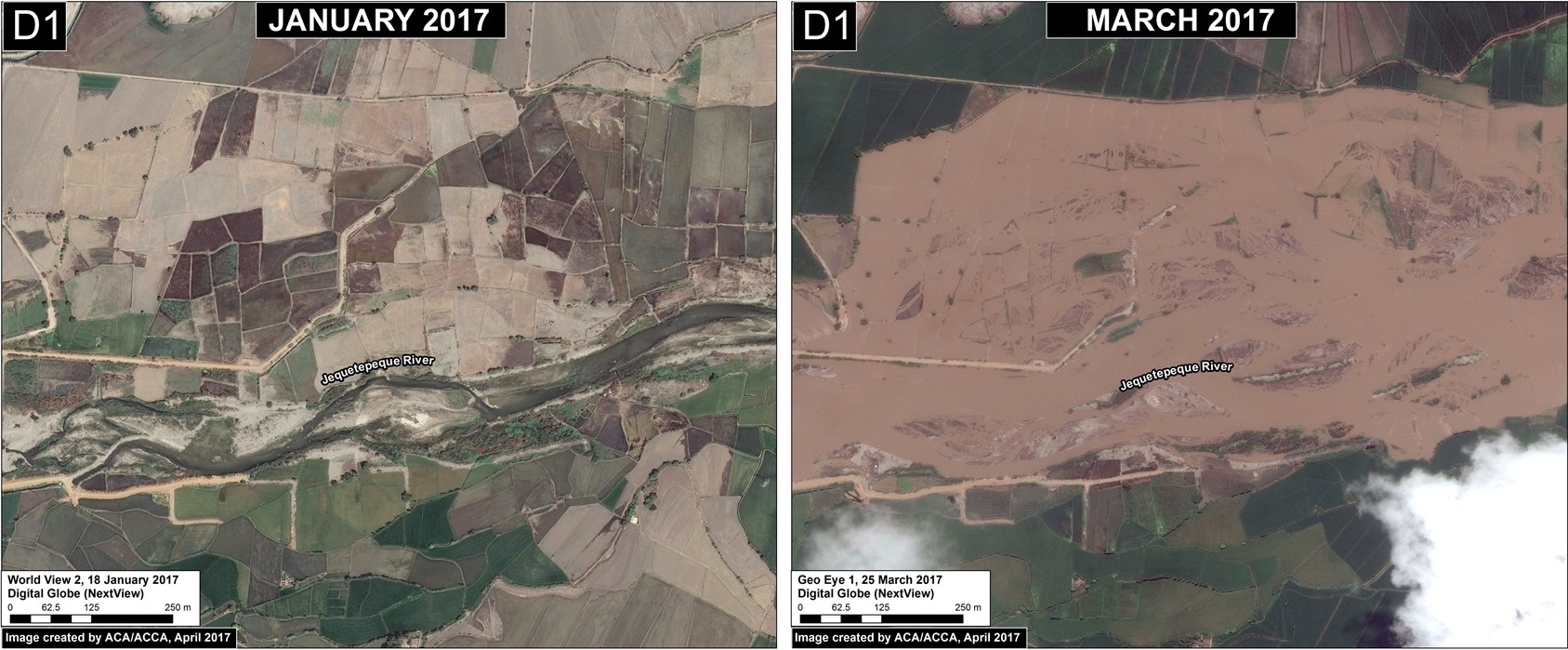

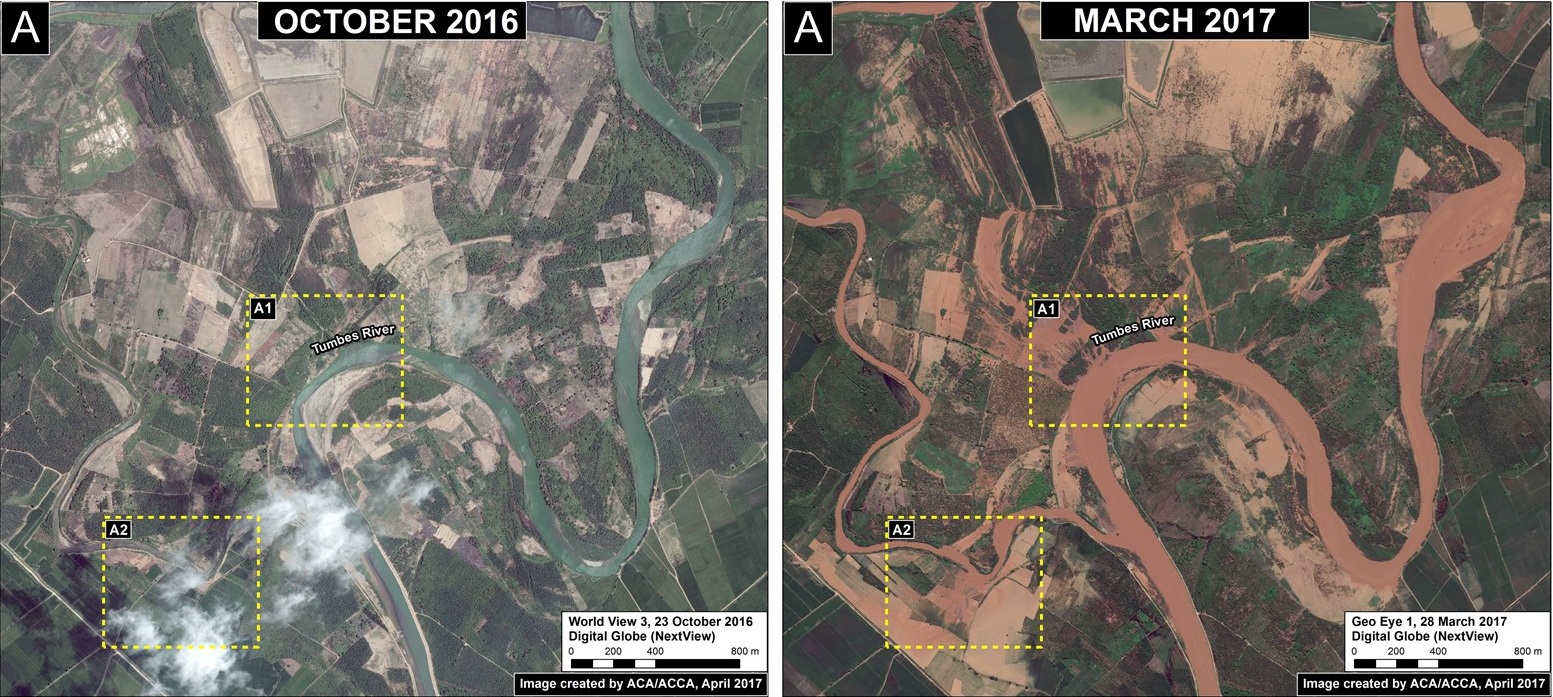

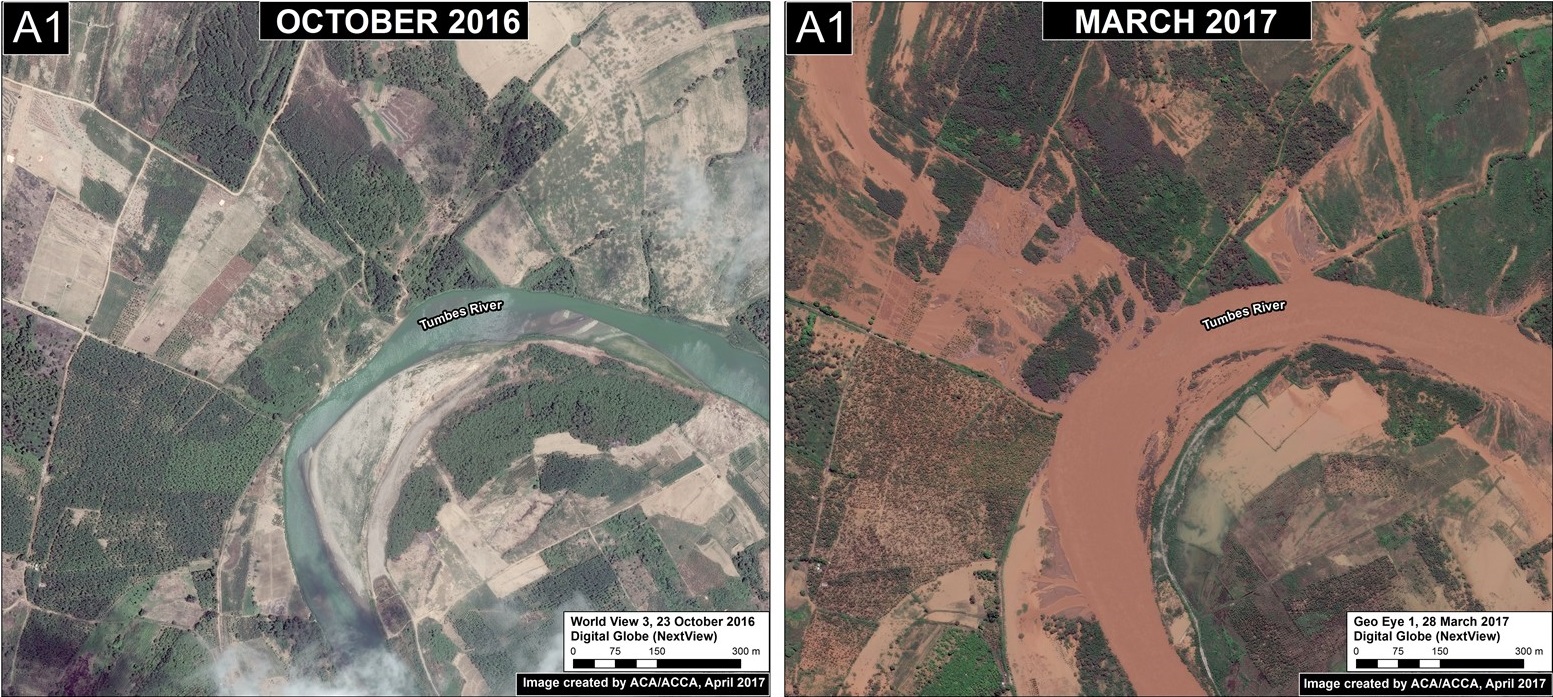

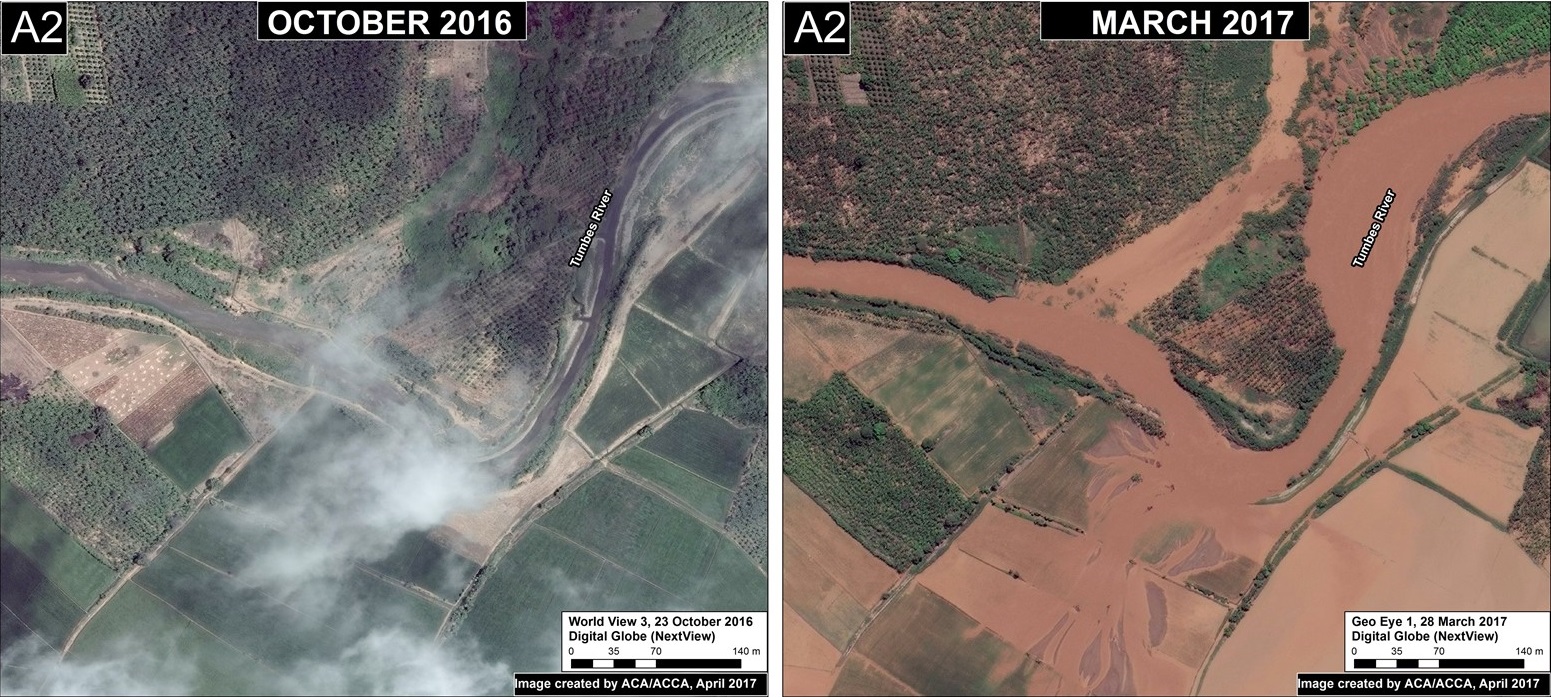

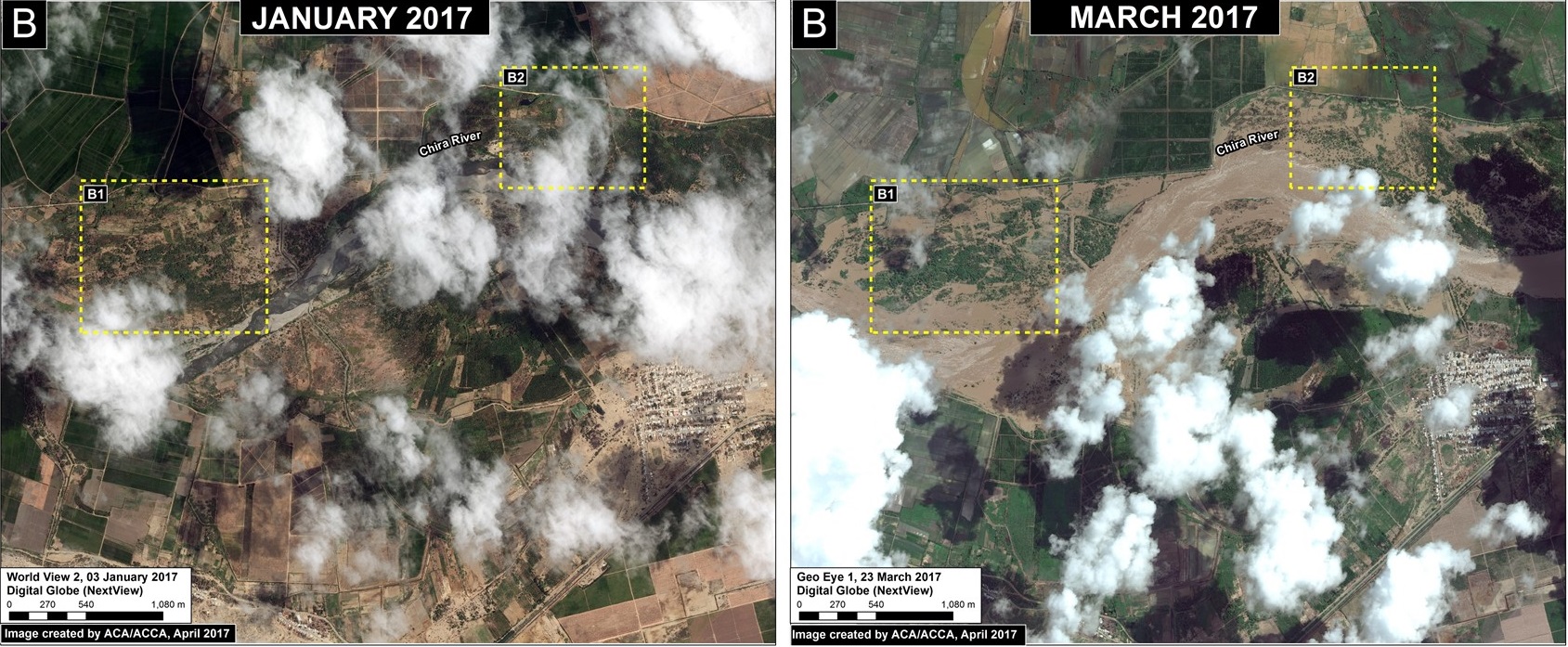

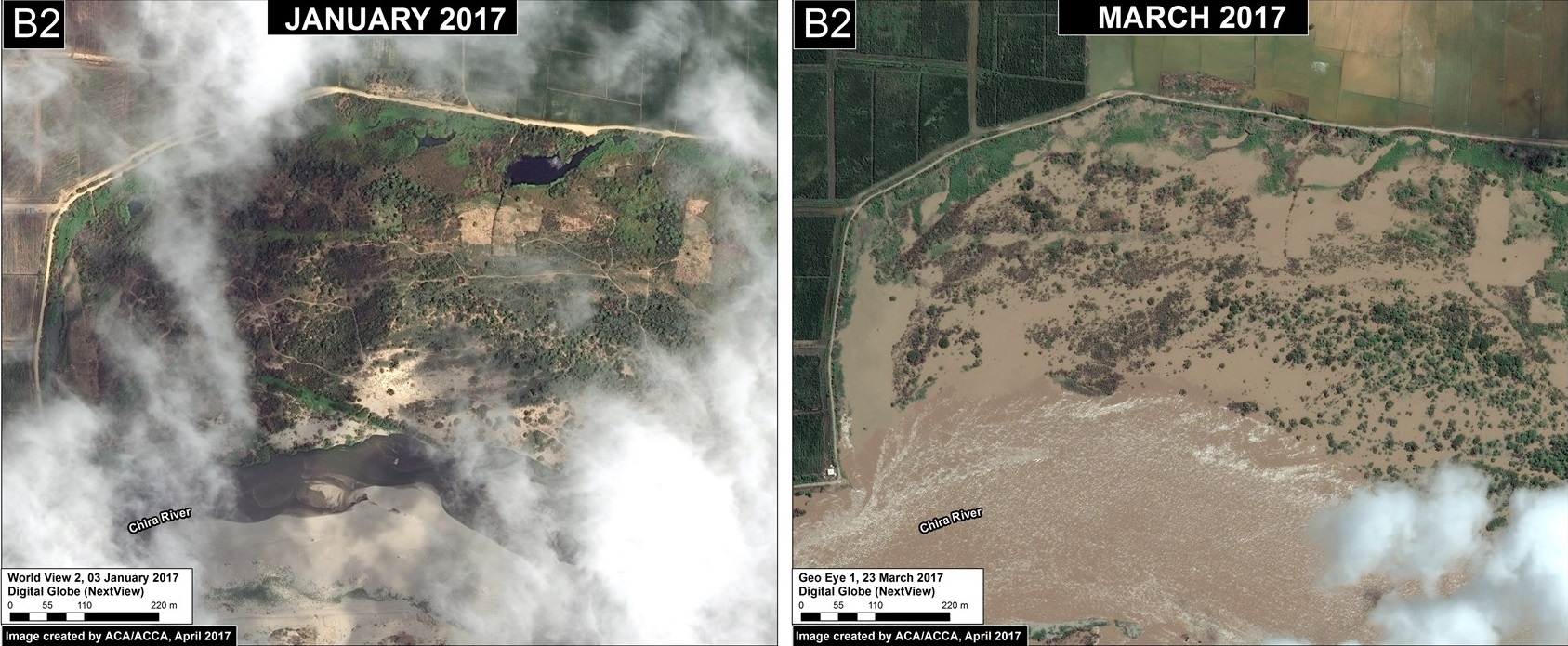

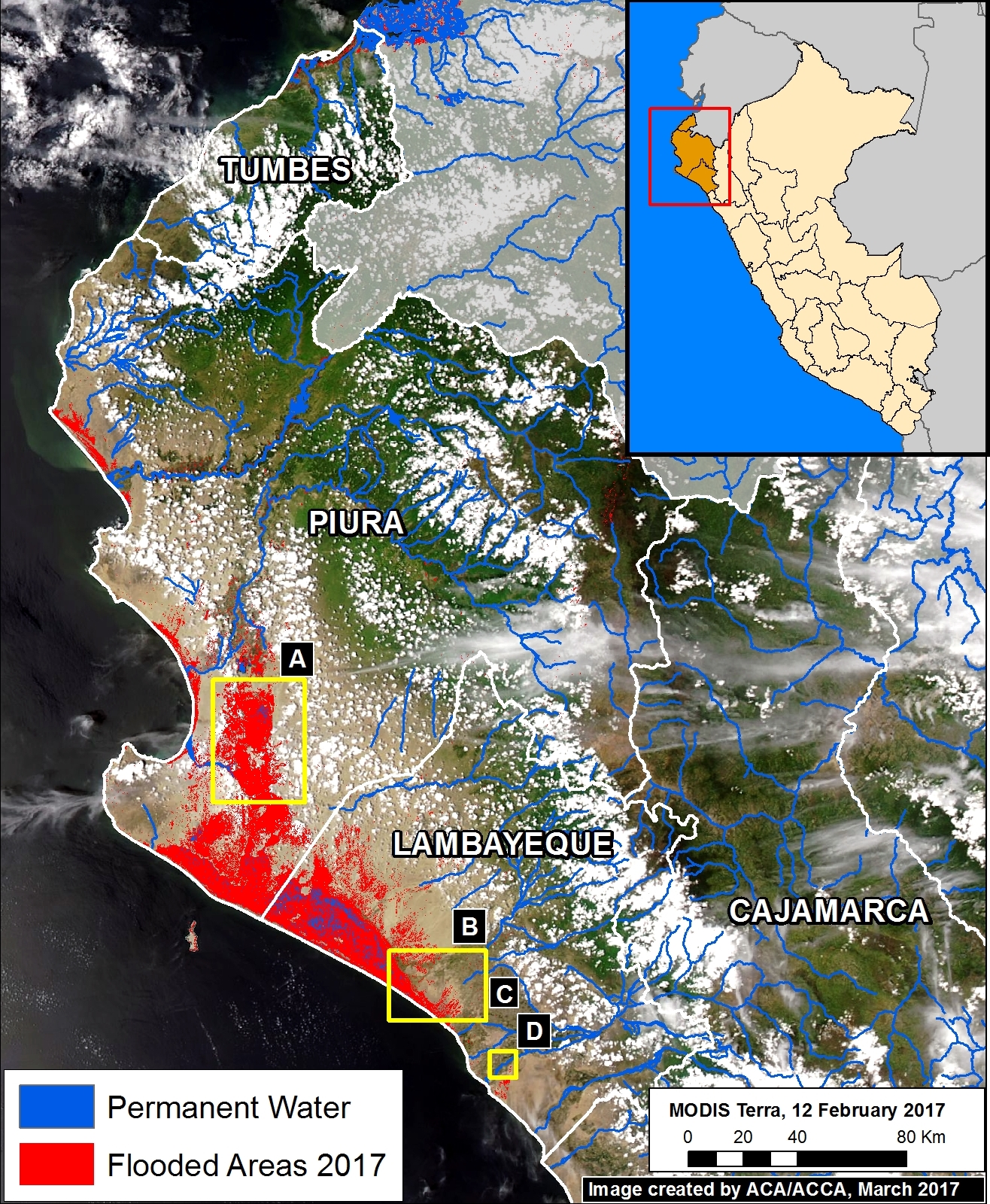

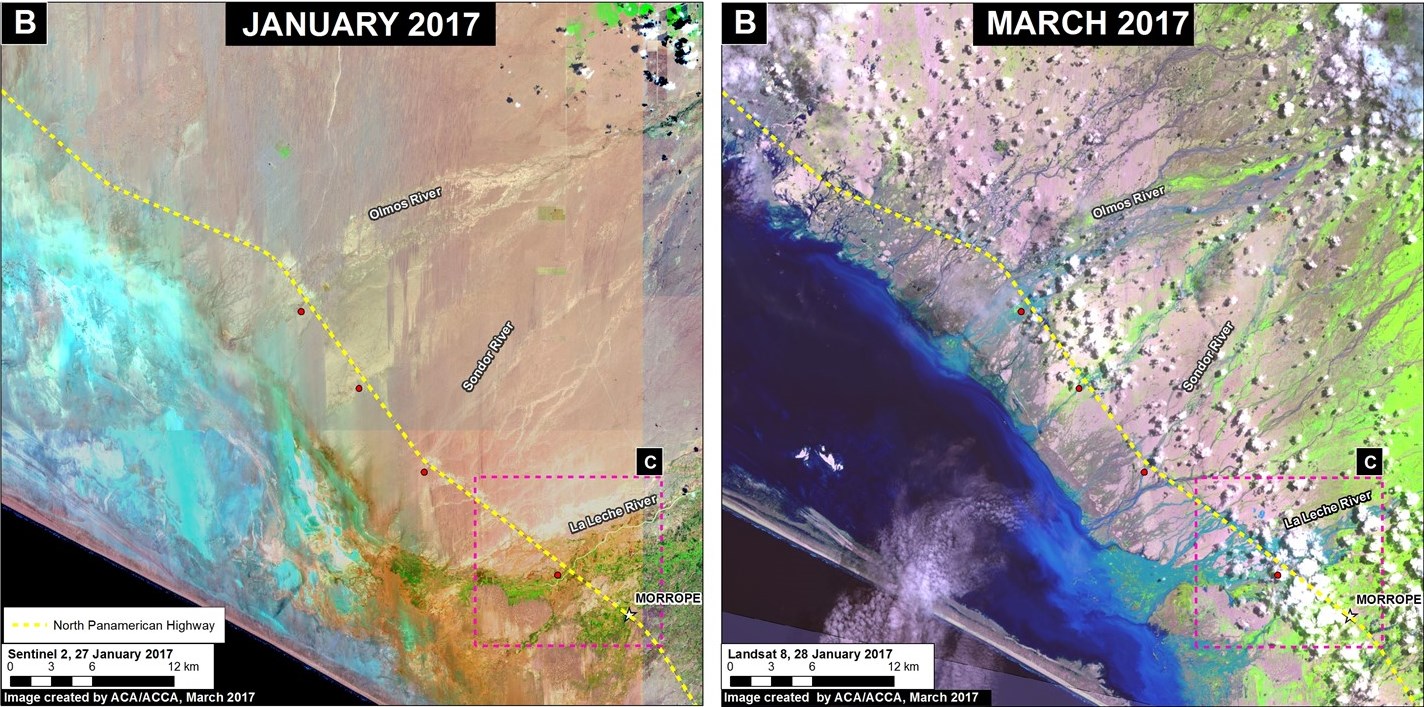

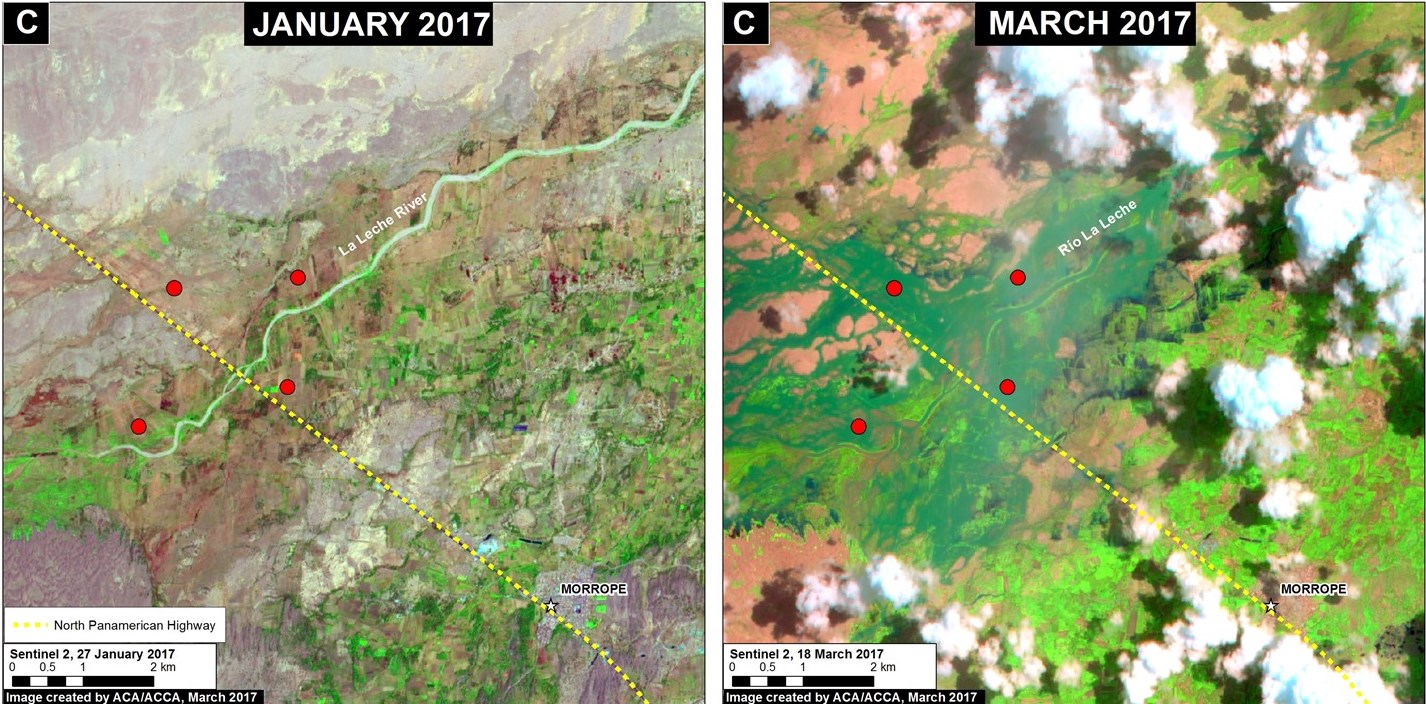

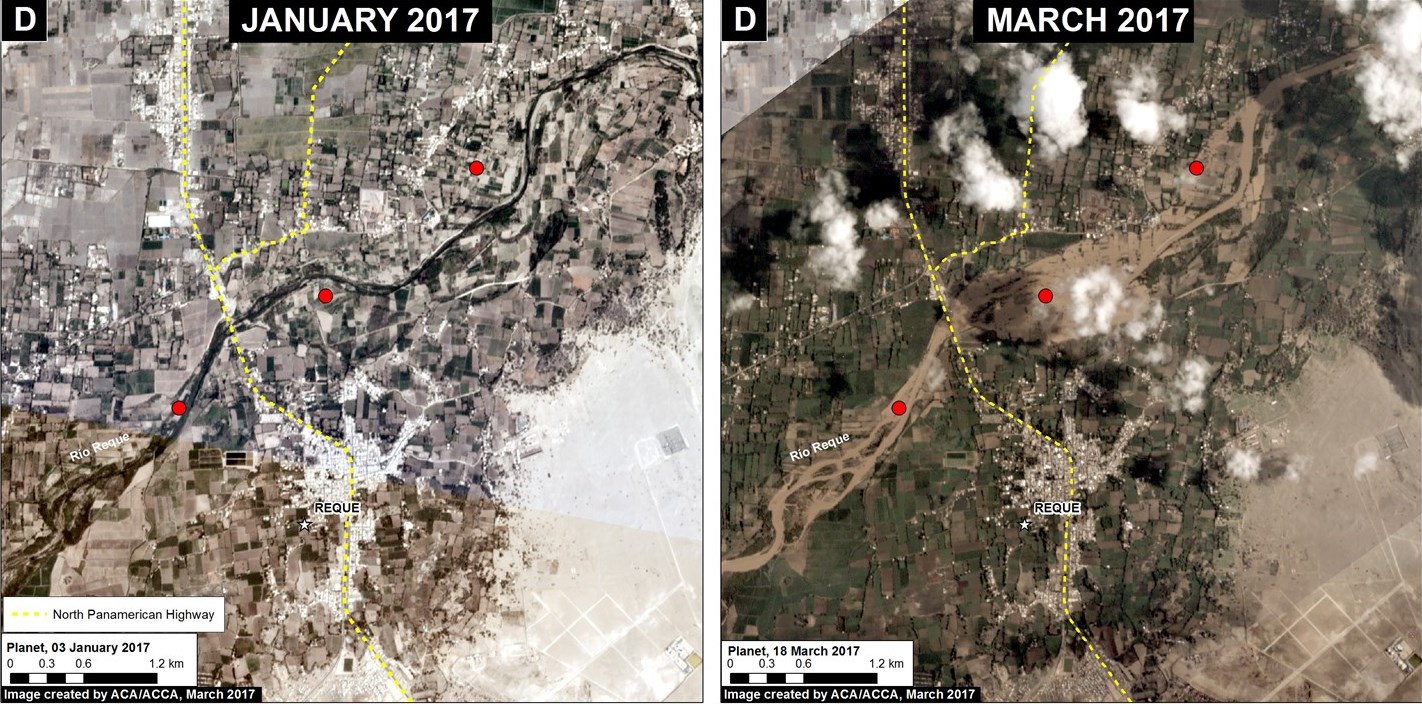

Floods

Finally, Planet imagery played a key role in monitoring the impacts of the recent deadly floods that hit the northern Peruvian coast. Image 59h shows the rapid flooding of agricultural plots along a river in northern Peru between February (left panel) and March (right panel) 2017.

References

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S, Mascaro J (2017) Power of “Small Satellites” from Planet. MAAP: 59.